Disneyland – Anaheim, California

I imagine if Mark Twain could have lived to witness Walt Disney’s interpretation of the American west in Frontierland, he would have been appalled. The revered natural landscapes have been reduced to something worse than a mere caricature. They’ve become a commodity, shrunken down into an easily digestible proportion. Although perhaps Twain would have appreciated the irony that the death of the authentic American experience should come in the form of a celebration of the authentic American experience.

I imagine if Mark Twain could have lived to witness Walt Disney’s interpretation of the American west in Frontierland, he would have been appalled. The revered natural landscapes have been reduced to something worse than a mere caricature. They’ve become a commodity, shrunken down into an easily digestible proportion. Although perhaps Twain would have appreciated the irony that the death of the authentic American experience should come in the form of a celebration of the authentic American experience.

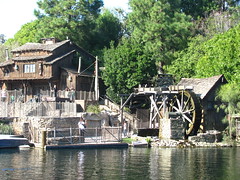

Has society really gotten to the point that we need the Rivers of America to substitute for the actual rivers of America? It’s too much to actually take the time and visit these locations ourselves? We want to romanticize nature but we’re no longer willing to earn it; the very qualities that made this terrain so romantic – the dangerous expanses of land that threaten to consume us as we confront the world standing at a small point across an incredible abyss of time – have all been replaced with the desire for simulated imposters. What does time mean in a theme park?

willing to earn it; the very qualities that made this terrain so romantic – the dangerous expanses of land that threaten to consume us as we confront the world standing at a small point across an incredible abyss of time – have all been replaced with the desire for simulated imposters. What does time mean in a theme park?

At a staggering twelve minutes long, the stately sternwheeler excursion aboard the Mark Twain Riverboat is about as slow-paced and idyllic as theme park attractions come. With most of our attention spans recently adjusted downward by dark rides that compress a 90 minute film into three minutes, many onlookers will be rhythmically tapping their toes with mild impatience when the next special sight fails to come into view within ten seconds after the Native American chief finished with his mechanical shtick. Disney teaches the younger generations that real nature is disappointing compared to his fabricated natural environment. It’s hard to tell the difference until we notice that one gets perfect what the other one got wrong. On this cruise the limestone formations are just a little too tidy and the moose are posing just a little too perfectly. Those with an appreciation for the real things will likely have little use in this environment, and those who’ve fallen in love with Disney’s nature are unlikely to have any taste left for the boring, dirty original. Maybe one can appreciate both by recognizing this as a multidimensional historical short documentary, although beware that half of the ‘sights’ our attention is called to are advertisements for other rides and attractions at Disneyland.

ten seconds after the Native American chief finished with his mechanical shtick. Disney teaches the younger generations that real nature is disappointing compared to his fabricated natural environment. It’s hard to tell the difference until we notice that one gets perfect what the other one got wrong. On this cruise the limestone formations are just a little too tidy and the moose are posing just a little too perfectly. Those with an appreciation for the real things will likely have little use in this environment, and those who’ve fallen in love with Disney’s nature are unlikely to have any taste left for the boring, dirty original. Maybe one can appreciate both by recognizing this as a multidimensional historical short documentary, although beware that half of the ‘sights’ our attention is called to are advertisements for other rides and attractions at Disneyland.

My ambivalence towards Frontierland might be because it’s simultaneously the most clichéd themed environment anywhere on Disney property, while also one of their most aesthetically displeasing. The emphasis on natural beauty clashes with the fact that most of Frontierland is anchored by a massive river of tourists filling the main arterial midway, which doubles as the viewing area for the nightly Fantasmic show. The closely contained energy of the narrow Adventureland and narrower New Orleans Square passageways ways gets sucked out into the vacuum as soon as we enter this massive concrete space. Missing is the camp humor found in Adventureland’s recreation of the comic books and serials that once held children in fascination. The relatively serious, “historically accurate” imitation of the old west, airbrushed to perfection, is rather bland and lifeless. The western town consists of a scant few structures such as the Golden Horseshoe Saloon, and they appear so clean and G-rated that one might wonder how Sam Peckinpah ever made a living. Disneyland excels when the experiences they craft have no conceivable better substitute anywhere else in the universe, either in the form of the authentic original or among their theme park competitors.1 At this, Frontierland doubly fails. Not only can you still find the real Frontierland without leaving the state of California, you can find a better theme park version of the same material without leaving Orange County.

or among their theme park competitors.1 At this, Frontierland doubly fails. Not only can you still find the real Frontierland without leaving the state of California, you can find a better theme park version of the same material without leaving Orange County.

What, then, would Frontierland do without Big Thunder Mountain Railroad? This classic 1979 attraction seems to get right the flair for self-consciously over-the-top theatricality and little touches of humor in the design that I found lacking from the rest of Frontierland. While Disney has never released any exact figures, I’ve heard rumors that, adjusted for inflation, this is the most expensive roller coaster ever built. A lot of the cash supposedly went into research and development on then-unproven steel coaster technology that engineers enjoy free use of today, but it certainly looks like that entire budget was put to use where all could see it as we depart the open-air boarding platform and duck into an elaborate bat-infested cavern on the approach to the first lift. A massive chamber filled with stalagmites and stalactites is discovered off to the left, appearing almost as if we’ve entered the belly of the leviathan as we proceed upward towards the light from the mouth. A cascade of water spilling over the tracks is split by an overhead boulder so we squeeze between the streams in a way that will make sure we keep our arms tucked in. Emerging into the sunlight, our runaway train makes a sharp right bank downhill and the adventure begins.

any exact figures, I’ve heard rumors that, adjusted for inflation, this is the most expensive roller coaster ever built. A lot of the cash supposedly went into research and development on then-unproven steel coaster technology that engineers enjoy free use of today, but it certainly looks like that entire budget was put to use where all could see it as we depart the open-air boarding platform and duck into an elaborate bat-infested cavern on the approach to the first lift. A massive chamber filled with stalagmites and stalactites is discovered off to the left, appearing almost as if we’ve entered the belly of the leviathan as we proceed upward towards the light from the mouth. A cascade of water spilling over the tracks is split by an overhead boulder so we squeeze between the streams in a way that will make sure we keep our arms tucked in. Emerging into the sunlight, our runaway train makes a sharp right bank downhill and the adventure begins.

Thunder Mountain’s greatest trick is that the elaborate mountain set allows the undulating track to remain at or below ground level at all times to dramatically enhance the sense of speed. Canyons, caves, and foliage limit our field of view so we can’t anticipate anything much more than fifty feet in advance, and the attraction is full of blink-and-you’ll-miss-it gags like an opossum literally thrown for a loop by our train, or a set of massive gears laid out like a Mickey Mouse head (although if you’re bored enough to be playing spot the mouse ears the ride isn’t doing what it’s supposed to). Granted, there still isn’t any dramatic sense of speed, considering it maxes out at 28 miles per hour, but questions of velocity become irrelevant once we realize we’re moving at the ideal clip to enjoy the scenery while still generating excitement. This technique wrings

Thunder Mountain’s greatest trick is that the elaborate mountain set allows the undulating track to remain at or below ground level at all times to dramatically enhance the sense of speed. Canyons, caves, and foliage limit our field of view so we can’t anticipate anything much more than fifty feet in advance, and the attraction is full of blink-and-you’ll-miss-it gags like an opossum literally thrown for a loop by our train, or a set of massive gears laid out like a Mickey Mouse head (although if you’re bored enough to be playing spot the mouse ears the ride isn’t doing what it’s supposed to). Granted, there still isn’t any dramatic sense of speed, considering it maxes out at 28 miles per hour, but questions of velocity become irrelevant once we realize we’re moving at the ideal clip to enjoy the scenery while still generating excitement. This technique wrings far more utility per foot of track than I would have imagined possible; there are three full minutes of continual, non-stop action, yet a 2671’ length is, incredibly, shorter than a ride like Top Thrill Dragster.

far more utility per foot of track than I would have imagined possible; there are three full minutes of continual, non-stop action, yet a 2671’ length is, incredibly, shorter than a ride like Top Thrill Dragster.

Yet with all of this successful theory, I can’t help but think that Big Thunder Mountain doesn’t live up to its full potential. For every attention paid to every detail, the broad scope of the entire roller coaster seems to be missing that timeless something. There are three sections of runaway coaster track between lift hills that each last no longer than thirty seconds for blocking purposes. The only dramatic progression I could find between these three sections is that each seemingly becomes even more randomized and meandering than the last. I’d have to mine deep into my memory recesses to recall any specific developments on this ride that weren’t a part of the show setting. Small dip, curve, curve, curving dip, hill, curve… I think there’s a full helix somewhere in the middle. Of course this is all fun in the moment, but my impression was that if Big Thunder Mountain was going to live up

Yet with all of this successful theory, I can’t help but think that Big Thunder Mountain doesn’t live up to its full potential. For every attention paid to every detail, the broad scope of the entire roller coaster seems to be missing that timeless something. There are three sections of runaway coaster track between lift hills that each last no longer than thirty seconds for blocking purposes. The only dramatic progression I could find between these three sections is that each seemingly becomes even more randomized and meandering than the last. I’d have to mine deep into my memory recesses to recall any specific developments on this ride that weren’t a part of the show setting. Small dip, curve, curve, curving dip, hill, curve… I think there’s a full helix somewhere in the middle. Of course this is all fun in the moment, but my impression was that if Big Thunder Mountain was going to live up to the classic status it is so often vaulted to, it was going to have to eventually pull a trick out of its hat that makes everyone stop and go “wow”, that one thing above all else we’ll remember about the ride. The first two acts are nearly indistinguishable from each other, with the same general speed, length, dynamics, curve-to-drop ratio, and so on… Finally, there’s dramatic progression inside the enclosed third lift, in which a dynamite “cave-in” effect (with bent track rails that cause the train to tip back and forth on the chain lift) seems to be intended as prelude to build tension and raise stakes before the big cathartic finish at the other end.

to the classic status it is so often vaulted to, it was going to have to eventually pull a trick out of its hat that makes everyone stop and go “wow”, that one thing above all else we’ll remember about the ride. The first two acts are nearly indistinguishable from each other, with the same general speed, length, dynamics, curve-to-drop ratio, and so on… Finally, there’s dramatic progression inside the enclosed third lift, in which a dynamite “cave-in” effect (with bent track rails that cause the train to tip back and forth on the chain lift) seems to be intended as prelude to build tension and raise stakes before the big cathartic finish at the other end.

We would be mistaken. What follows is the shortest, slowest and gentlest of the three gravity-driven portions of track, in plain view of the queue and midways, such that the story becomes actively anticlimactic. After a generic set of more curves and dips, what’s our spectacular finale that defines the lasting memory everyone will take home? A small water splashdown beneath a cheesy dinosaur fossil. I found this disappointing for at least three reasons:

A): We’ve already seen this finale from the queue so no element of it is a surprise.

A): We’ve already seen this finale from the queue so no element of it is a surprise.

B): It does relatively little to enhance the passenger experience, designed more for the visual appeal for spectators (see point A).

C): The idea is obviously carbon-copied from Big Thunder Mountain’s predecessor, the Matterhorn, only to lesser success. Not only does this immediately signal cheap creative shortcutting by a company that should know better, but the Matterhorn sports a real splashdown that’s as thrilling to riders as spectators. Meanwhile, Big Thunder Mountain’s splash appears obviously staged with the row of water nozzles “hidden” beneath the track that’s nowhere close to skimming the water.

It’s probably my own damn fault for coming away from Big Thunder Mountain so very underwhelmed, because I made the mistake of riding the Parisian version first. That attraction, the fourth Big Thunder iterant that opened in 1992 with help from Vekoma, has a truly incredible finale: a long continuous descent into an underground cavern that nearly doubles the top speed of the ride before bottoming out beneath the Rivers of America basin. The entire ride is defined by that finale. Every moment, no matter how arbitrary, is contextualized by the fact that it moves us inexorably closer to that final descent. The fast-building momentum at the end creates a slow-building momentum throughout the first two-thirds. The California version is the inverse, and although I always knew it would be weaker by comparison, the resulting psychological payoff is displaced by several magnitudes.

slow-building momentum throughout the first two-thirds. The California version is the inverse, and although I always knew it would be weaker by comparison, the resulting psychological payoff is displaced by several magnitudes.

Perhaps it’s unfair to compare the original against the newest model, and I’m not respecting the achievement Big Thunder Mountain Railroad was for its time. Nevertheless, I’ll argue that even Arrow Dynamics had achieved much more compelling layout narratives more than a decade prior, and with far more limited resources. All of the original Six Flags mine trains in Texas, Georgia, and Missouri end with their largest, steepest drops, unforeseen into an underground (or underwater!) tunnel. Installations at Magic Mountain, Cedar Point, and Hersheypark all finish with accelerating downward helices that manage to rouse some emotions (and lateral forces) before reaching the final brake run. Even King’s Island’s Adventure Express… well, at least people will always remember and talk about that finale!

with accelerating downward helices that manage to rouse some emotions (and lateral forces) before reaching the final brake run. Even King’s Island’s Adventure Express… well, at least people will always remember and talk about that finale!

Maybe someday I’ll have a chance to return and give the Big Thunder Mountain Railroad another chance. Maybe it will finally click for me, and I’ll understand why it is one of the most-loved mine trains ever built. Maybe I’ll get off it and think to myself, “ya’know, that’s a really good roller coaster.”

Or maybe not.

We did not venture onto Tom Sawyer Island on this occasion; perhaps I would have warmed to Frontierland more if we had. Of this I’m skeptical, however, as my park guide tells me that the island has recently been rethemed to replace all of the musty Twain literary references with newfangled tie-ins to the Pirates of the Caribbean film franchise. Huh, pirates in the pioneer west? Well, I guess that’s not quite as bad as Six Flags’ positioning of Greek mythology in their western theme section, especially since they didn’t have the opportunity to promote a lucrative intellectual property as an excuse. While I can’t account for any personal experiences with swashbucklers stranded rural America, my aunt Christine whom I was visiting with did have a story to share about this island. She recalled that on her second date

We did not venture onto Tom Sawyer Island on this occasion; perhaps I would have warmed to Frontierland more if we had. Of this I’m skeptical, however, as my park guide tells me that the island has recently been rethemed to replace all of the musty Twain literary references with newfangled tie-ins to the Pirates of the Caribbean film franchise. Huh, pirates in the pioneer west? Well, I guess that’s not quite as bad as Six Flags’ positioning of Greek mythology in their western theme section, especially since they didn’t have the opportunity to promote a lucrative intellectual property as an excuse. While I can’t account for any personal experiences with swashbucklers stranded rural America, my aunt Christine whom I was visiting with did have a story to share about this island. She recalled that on her second date with my uncle they went to Disneyland, where they shared a jarred pickle together at the food stand on Tom Sawyer Island. When they finished they still had the container of pickle juice left over. Rather than dump it, she offered to drink the remainder. This amazed my uncle because he thought he was the only person in the world that drank plain pickle juice. After their Disneyland date finished he called his parents and told them “I think I’ve finally met the girl I want to marry! She also likes pickle juice!”

with my uncle they went to Disneyland, where they shared a jarred pickle together at the food stand on Tom Sawyer Island. When they finished they still had the container of pickle juice left over. Rather than dump it, she offered to drink the remainder. This amazed my uncle because he thought he was the only person in the world that drank plain pickle juice. After their Disneyland date finished he called his parents and told them “I think I’ve finally met the girl I want to marry! She also likes pickle juice!”

I guess sometimes there are real happily-ever-after stories at Disneyland.

Footnotes & Annotations

[1] A hyperreal environment is always limited by the comparison to the place it imitates, regardless if the source is an exact real-life counterpart or a historical fiction that never actually existed. No matter how “good” Frontierland is, it could always be “better” if it were somehow believed to be the authentic Old West, and is therefore always judged to be “imperfect” by this failed criterion. The Great Disneyland Experiences embrace rather than hide the fact that they are telling a story with theme park technology, which results in an originality of experience that effectively removes comparison to any alternative, idealized world outside of Disney’s gates, thereby allowing the attraction to achieve “perfection”.

Big Thunder was a resounding disappointment when I rode it opening year and repeat rides over the years just reinforced that opinion. I won’t even bother with it anymore.