Shanghai, China – Thursday, September 8th & Friday, September 9th, 2016

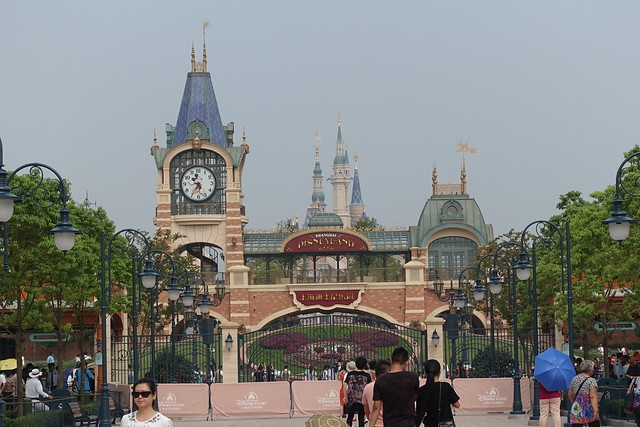

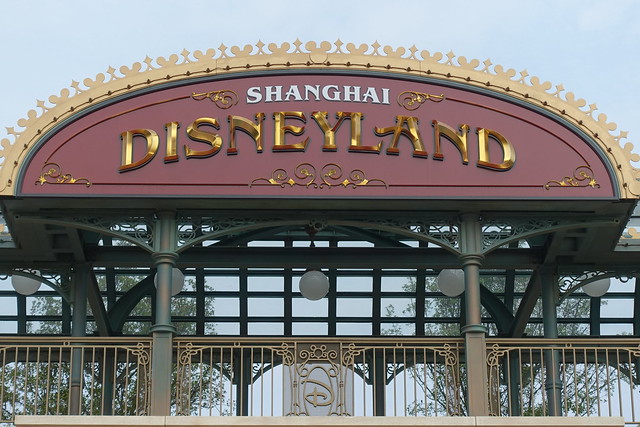

Shanghai Disneyland is the sixth Magic Kingdom-style Disney park whose gates I walked through. Looking around on my first visit during the grand opening year of 2016, some things immediately appear familiar: There’s the Main Street train station to guard over the entrance, slightly larger than the others (yet without train). In some ways this entrance makes Shanghai more typical to the form than either Paris or Tokyo, with their imposing architectural statements placed up front. But there’s also a key difference with this entryway that marks it as perhaps a more radical departure over all the other Magic Kingdom-style parks.

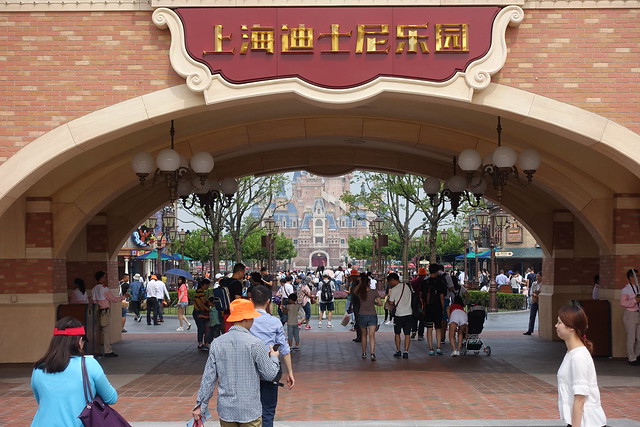

This large scale, centrally-positioned portal serves a vastly different role than the other Magic Kingdom-style parks, which are narrow and in most cases split to either side of the station, to create a compression moment and stronger sense of separation and passageway from the outside world and in; the traditionally offset design also requires visitors to enter Main Street Plaza from the edges so that they will wander and absorb the atmosphere of the town square for several moments before revealing the central Main Street corridor with the castle punctuating the end as the climax of this arrival sequence. At Shanghai, this sequence is wholly replaced with singular, static spectacle.

This large scale, centrally-positioned portal serves a vastly different role than the other Magic Kingdom-style parks, which are narrow and in most cases split to either side of the station, to create a compression moment and stronger sense of separation and passageway from the outside world and in; the traditionally offset design also requires visitors to enter Main Street Plaza from the edges so that they will wander and absorb the atmosphere of the town square for several moments before revealing the central Main Street corridor with the castle punctuating the end as the climax of this arrival sequence. At Shanghai, this sequence is wholly replaced with singular, static spectacle.

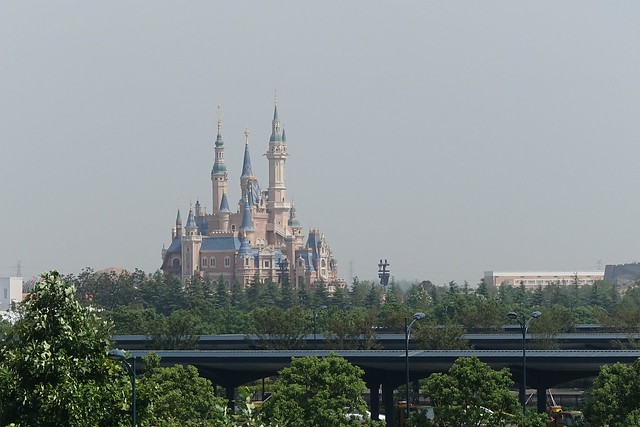

Before you even enter the park, the castle peaks out above the landscape, beckoning from miles away.

The walkway through the trainless train station forgoes the small, wordy plaques that introduce the thesis of Disneyland’s multi-land narrative structure, in favor of a singular, unified entry statement that is simply summarized as “Shanghai Disneyland”.

The portal does little to mask or compress the transition from outside world to inside. Instead, it functions more as a frame around the castle to mark the correct perspective and heighten the sense of scale.

One last thing to note: the keystones to the archways feature beveled “Disney D” corporate icons, and, atop it all, the traditional old-time clock face is replaced with a friendly (and contemporary) Mickey Mouse pointing to the day’s time.

This entrance pretty well summarizes what makes Shanghai Disneyland different from all the other Magic Kingdom-style parks.1 On the surface everything is familiar, but in function it all serves very different ends. At every turn, the park is built for spectacle. The “Story” is now often reducible to the “Icon”. This is somewhat ironic given that individual attractions within the park become more narratively focused than ever before. But the focus of the park as a whole is no longer about the balanced sequence of discovery between distinct lands, but about the unification of the entire property around the singular icon for the Disney Empire:

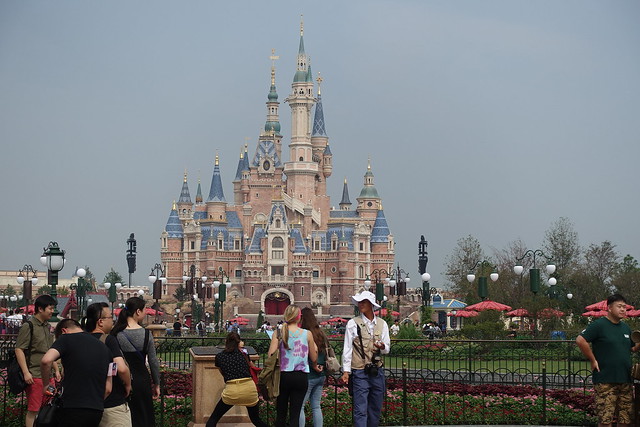

Seriously, look at how big this castle is:

The castle is no longer just a gateway and symbol for Fantasyland, but is the central icon that encompasses everything on the Shanghai Disneyland property. Of course the castle has always served this central symbolic role to some degree, but from 1955 to 2016 that role has shifted from an honorary designation to an absolute justification – not just for its own existence, but for the existence of the entire park surrounding the castle. The castle doesn’t so much support the lands as it is that the lands support the castle.

The castle is no longer just a gateway and symbol for Fantasyland, but is the central icon that encompasses everything on the Shanghai Disneyland property. Of course the castle has always served this central symbolic role to some degree, but from 1955 to 2016 that role has shifted from an honorary designation to an absolute justification – not just for its own existence, but for the existence of the entire park surrounding the castle. The castle doesn’t so much support the lands as it is that the lands support the castle.

The vision for Shanghai Disneyland was (very) often touted by Bob Iger as being “authentically

The vision for Shanghai Disneyland was (very) often touted by Bob Iger as being “authentically Disney and distinctly Chinese”. At its most obvious interpretation suggests the park will balance and blend both Disney and Chinese elements, and indeed this can be seen in some obvious places, in particular around the Gardens of Imagination where the Wandering Moon Teahouse sits opposite Dumbo the Flying Elephant, and the Garden of the Twelve Friends finds a none-too-subtle connection between both traditions. Yet after visiting the park, I had to unpack this default viewpoint of a binary symbiosis in favor of a different interpretation: Shanghai Disneyland became more distinctly Chinese by becoming more authentically Disney.

Disney and distinctly Chinese”. At its most obvious interpretation suggests the park will balance and blend both Disney and Chinese elements, and indeed this can be seen in some obvious places, in particular around the Gardens of Imagination where the Wandering Moon Teahouse sits opposite Dumbo the Flying Elephant, and the Garden of the Twelve Friends finds a none-too-subtle connection between both traditions. Yet after visiting the park, I had to unpack this default viewpoint of a binary symbiosis in favor of a different interpretation: Shanghai Disneyland became more distinctly Chinese by becoming more authentically Disney.

This sounds strange, but the truth is that the original form of the Magic Kingdom parks was never particularly concerned with representing Disney as a brand. Castle and pixie dust have traditionally been a very small sliver of the Disney theme park identity. Despite the highly specific Disney identity created through marketing outside the parks (and evident inside the parks primarily through costumed characters, parades, and shows), the overall themes of the Magic Kingdom parks have long been more archetypal, evoking broad cultural and national narratives, while the details often skewed towards the culturally specific, sometimes even the esoteric (at least for 21st century audiences). Shanghai Disneyland turns this approach on its head, with the overall themes of the park becoming highly specific – the branded content of the Disney canon – while the details have become more generic, more formally idealized, more readable without cultural context beyond a basic familiarity with the intellectual properties being presented. The fact that China is now the official host and cultural peer to this most spectacularly scaled expression of a globally-recognized brand is what makes Shanghai Disneyland simultaneously authentically Disney and distinctly Chinese. The modern Disney brand promises grandiosity and spectacle, and Chinese audiences, tired of second-tier knock-offs, now distinctly demand the most authentic expression of that global brand, stripped of the specific cultural quirks that were a cornerstone of previous parks.

of the Disney theme park identity. Despite the highly specific Disney identity created through marketing outside the parks (and evident inside the parks primarily through costumed characters, parades, and shows), the overall themes of the Magic Kingdom parks have long been more archetypal, evoking broad cultural and national narratives, while the details often skewed towards the culturally specific, sometimes even the esoteric (at least for 21st century audiences). Shanghai Disneyland turns this approach on its head, with the overall themes of the park becoming highly specific – the branded content of the Disney canon – while the details have become more generic, more formally idealized, more readable without cultural context beyond a basic familiarity with the intellectual properties being presented. The fact that China is now the official host and cultural peer to this most spectacularly scaled expression of a globally-recognized brand is what makes Shanghai Disneyland simultaneously authentically Disney and distinctly Chinese. The modern Disney brand promises grandiosity and spectacle, and Chinese audiences, tired of second-tier knock-offs, now distinctly demand the most authentic expression of that global brand, stripped of the specific cultural quirks that were a cornerstone of previous parks.

This emphasis on representing the Disney brand over more traditional themed storytelling is nothing new within Imagineering, but it is the first time that their recent design practices for rides and themed lands has been scaled up to encompass an entirely new master planned theme park. It’s particularly evident when you look at the balance of Shanghai Disneyland, which is radically different from any other Magic Kingdom park — and not just because the designated Tomorrowland and Adventureland zones swapped sides. The whole central corridor, reaching from Mickey Avenue through Gardens of Imagination to Fantasyland, is now one giant “Classic Disney” brand zone. Mickey Avenue is basically

This emphasis on representing the Disney brand over more traditional themed storytelling is nothing new within Imagineering, but it is the first time that their recent design practices for rides and themed lands has been scaled up to encompass an entirely new master planned theme park. It’s particularly evident when you look at the balance of Shanghai Disneyland, which is radically different from any other Magic Kingdom park — and not just because the designated Tomorrowland and Adventureland zones swapped sides. The whole central corridor, reaching from Mickey Avenue through Gardens of Imagination to Fantasyland, is now one giant “Classic Disney” brand zone. Mickey Avenue is basically “Disney Characters in America”, Gardens of Imagination is “Disney Characters in China”, and Fantasyland is “Disney Characters in Europe”.

“Disney Characters in America”, Gardens of Imagination is “Disney Characters in China”, and Fantasyland is “Disney Characters in Europe”.

While each of these three zones has its own design language, the heavy Disney character unifies and eases the transitions in this corridor in ways that traditional Main Street, Hub, and Fantasyland designs kept segmented. This corridor is also massive, with the combined area easily taking up a majority of the park acreage. The traditional “Hub-and-Spoke” design is replaced with a ringed “Lollypop” or “Butterfly” layout, with a broad parade artery circling around the Gardens of Imagination and Fantasyland to separate these areas as the “core”, while Tomorrowland and the combined Adventurelands now feel like secondary wings on either side, as if they’re outlying vassal states on the outskirts of this Magic Kingdom’s territory. The masterplan is not necessarily off-balance in the same way that the expansion rings around the western sides of Hong Kong and now Anaheim have thrown those parks slightly askew, but there is an unequal balance in which not all lands and brands get their fair share when seated around a circular table. There’s a thematic hierarchy in this park’s layout used to accentuate the spectacle over the sequence, one that doesn’t exist in any of the other Magic Kingdoms, and that’s what makes Shanghai Disneyland such a radical departure.

combined Adventurelands now feel like secondary wings on either side, as if they’re outlying vassal states on the outskirts of this Magic Kingdom’s territory. The masterplan is not necessarily off-balance in the same way that the expansion rings around the western sides of Hong Kong and now Anaheim have thrown those parks slightly askew, but there is an unequal balance in which not all lands and brands get their fair share when seated around a circular table. There’s a thematic hierarchy in this park’s layout used to accentuate the spectacle over the sequence, one that doesn’t exist in any of the other Magic Kingdoms, and that’s what makes Shanghai Disneyland such a radical departure.

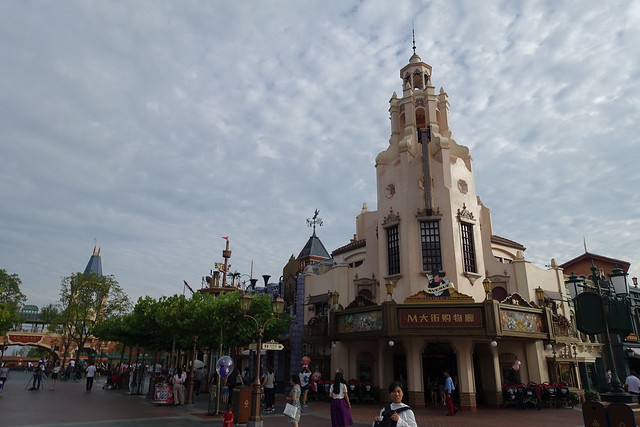

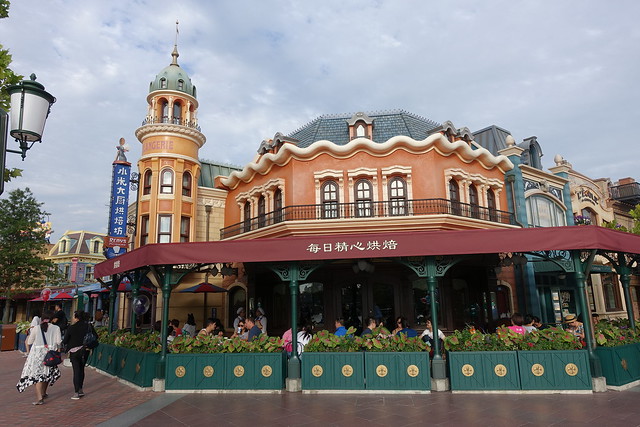

So let’s take a tour of Shanghai Disneyland. The park begins with Mickey Avenue, one of the newly designed lands just for Shanghai Disneyland that replaces the more culturally specific Main Street U.S.A. with a brand specific street filled with Disney characters.

On paper, a description of Mickey Avenue can seem positively groan inducing: A street inhabited by all the Disney cartoon characters sounds an awful lot like it could go the route of Toontown, but with random bits of architectural design pulled from the blueprints from recent projects like Buena Vista Street at California Adventure or Ratatouille at the Studios Park.

On paper, a description of Mickey Avenue can seem positively groan inducing: A street inhabited by all the Disney cartoon characters sounds an awful lot like it could go the route of Toontown, but with random bits of architectural design pulled from the blueprints from recent projects like Buena Vista Street at California Adventure or Ratatouille at the Studios Park.

Fortunately, instead of the dog’s breakfast I might have expected, Mickey Avenue thankfully forgoes the oversaturated, ballooning aesthetic of Toontown in favor of a consistent design language of real architecture, yet with a more defined sense of place and story, and enough whimsical details that it doesn’t come off as just another outdoor dining and retail district. It’s about as clever and tasteful as you could hope of a Disney themed environment called “Mickey Avenue”.

Fortunately, instead of the dog’s breakfast I might have expected, Mickey Avenue thankfully forgoes the oversaturated, ballooning aesthetic of Toontown in favor of a consistent design language of real architecture, yet with a more defined sense of place and story, and enough whimsical details that it doesn’t come off as just another outdoor dining and retail district. It’s about as clever and tasteful as you could hope of a Disney themed environment called “Mickey Avenue”.

If I have one major criticism of Mickey Avenue, it’s that it, like many theme park entry avenues, the route is experientially empty, overstuffed with food and retail that you simply have to walk through if you’re not interested in buying anything. There are fun details to notice, but it doesn’t get much deeper than that. Since the entry street is basically a cul-de-sac except for when you’re entering and leaving the park, Mickey Avenue doesn’t get much natural usage during the middle of the day unless you want to go out of your way for a food option not available in one of the other lands, or at the end of the day during the souvenir rush.

If I have one major criticism of Mickey Avenue, it’s that it, like many theme park entry avenues, the route is experientially empty, overstuffed with food and retail that you simply have to walk through if you’re not interested in buying anything. There are fun details to notice, but it doesn’t get much deeper than that. Since the entry street is basically a cul-de-sac except for when you’re entering and leaving the park, Mickey Avenue doesn’t get much natural usage during the middle of the day unless you want to go out of your way for a food option not available in one of the other lands, or at the end of the day during the souvenir rush.

The Walt and Mickey “Partners” statue makes an appearance at the end of Mickey Avenue. Interestingly, they went with the design from California Adventure rather than the standard Walt statues from the other parks. My hunch is that Walt’s outstretched arm in the standard statute may be too reminiscent of Chairman Mao, so they went with a statue that makes him look more casual and American.

Next, Gardens of Imagination replaces the Hub at the center of the park with a significantly expanded land featuring several rides and attractions. It’s this addition that in my opinion marks the most radical departure from previous Magic Kingdom parks since it changes the sense of balance and center. It is, nevertheless, a welcome addition, providing a nice landscaped area to explore and escape the crowds, as well as becoming a palette cleanser when traversing between lands:

It’s also where most of the specifically Chinese elements of Shanghai Disney have ended up, and the overall concept of a large garden area was intended to appeal to Chinese audiences. Whether these were legitimately included to appeal to Chinese audiences or if they were included more to appease government officials mindful of making certain “Chinese cultural quotas” in approving the park design, I can’t say for sure. Notable among these is the Chinese Zodiac-inspired Garden of the Twelve Friends:

Wandering Moon Teahouse:

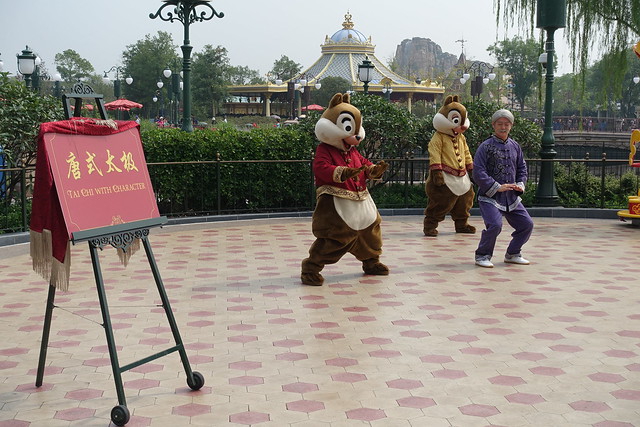

And, perhaps most oddly, was a morning event we stumbled upon called “Tai Chi with Character”.

Okay, so I get the costumed Chip and Dale, but why does the instructor also wear such a phony costume?

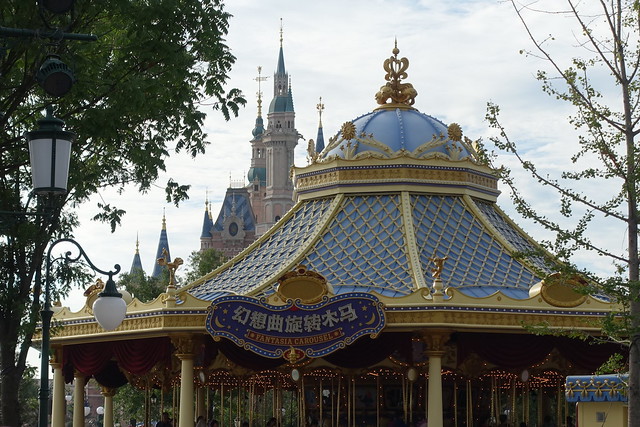

To balance out the Chinese elements (and, for once, to have some actual attractions before reaching the castle), there are a couple of classic Disney rides that I guess were too iconic to tuck away in Fantasyland, where they might be thematically ill-fitted anyway: Dumbo the Flying Elephant and Fantasia Carousel.

I didn’t ride either.

A parade called Mickey’s Storybook Express also wraps around the wide avenue surrounding the Gardens of Imagination a couple times each day. I missed the beginning, but the overall concept is apparently that of a railroad train with different character floats as “cars”.

Unfortunately while the float and costume design is generally all very competent, this is one of the more cloying examples of Disney’s “character stew” approach to their theme parks, that often seems to manifest itself the worst in live entertainment. The parade seems designed not so much by a creative director but a marketing director, one determined to cram in only the top IP’s they want to push that season, and finding the flimsiest excuse for a “story” to bookend it.

Also, while Chinese patron behavior overall was not any better or worse than anything you’d find at the American parks,2 the one key cultural difference to watch out for is umbrellas. It’s not raining. For whatever reason, many Chinese people don’t like sunscreen, and instead will bring umbrellas to protect them from the sunlight, even if they’re standing in the front row of a parade or show.

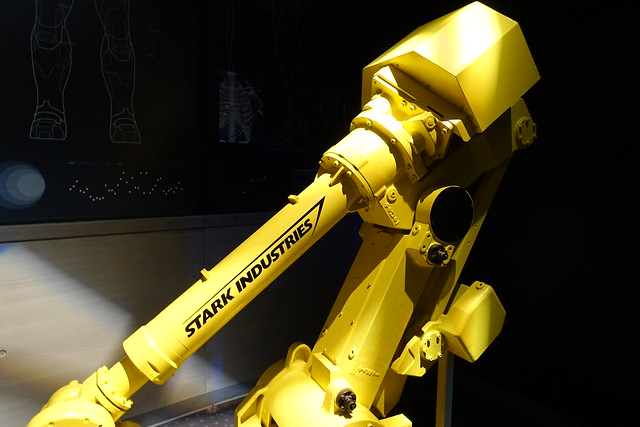

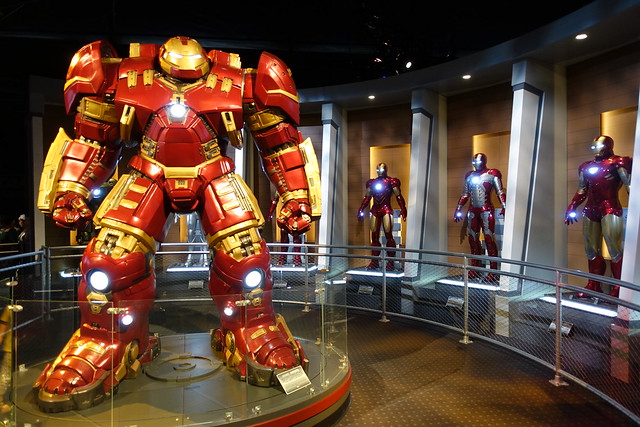

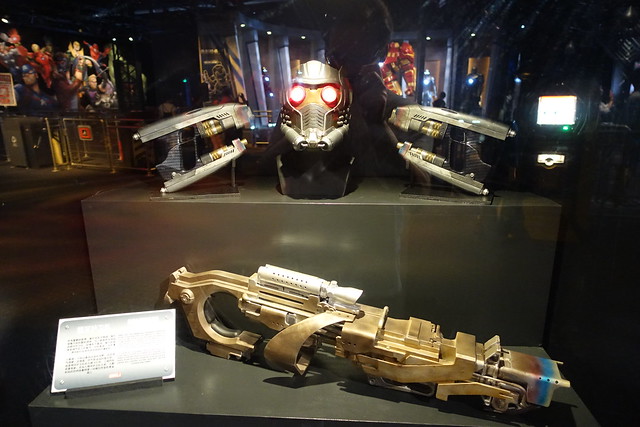

The Gardens of Imagination is also somewhat idiosyncratically home to the Marvel Universe exhibit. The fact that Marvel and Star Wars (purchased by Disney in 2012) are represented by low-budget exhibits stuffed into small buildings in odd locations in the park, while 2010’s TRON got an elaborate E-ticket anchor attraction at the center of Tomorrowland, should give you a pretty good idea of the timeline when master plans for Shanghai Disneyland were greenlit and locked.

Inside Marvel Universe are a lot of fairly cheap interactives and 2D character cut-outs. How is it that Disney has had the rights to Marvel for over four years and this is still the best use they can put in their parks?

On the plus side, their Captain America was actually American! (Or at least Canadian as a possible alternative.) Of course, lines of Chinese people wanting to get their photo taken with a white foreigner is nothing new.

Footnotes & Annotations

[1] Of course they’re all different from each other, but this one perhaps moves further from the median than any park that came before it. Anaheim and Orlando established the form, Paris elaborated on it using the masters who learned from their work on the first two parks, while Tokyo and Hong Kong basically carbon-copied Orlando and Anaheim respectively, at least with their opening day designs. This makes Shanghai Disneyland somewhat unprecedented: a Magic Kingdom-style park for the first time designed entirely by a generation of Imagineers without a direct line of connection to the original.

[2] Blog posts showing the most egregious examples of guest behavior at Shanghai Disneyland are often just as if not more loudly criticized by fellow Chinese than people overseas.