Disneyland – Anaheim, California_______________

On July 17th, 1955, Walt Disney debuted to the world his vision for Disneyland, welcoming the very first patrons to this happy place dedicated to the ideals, the dreams, and the hard facts that created America. While the dedication would make the history books, the rest of the day would be referred to within the company as Black Sunday. From that moment on, the American amusement park would be irreversibly ruined.

It wasn’t the overcrowding, the unfinished cement walkways, the lack of water supply, or the gas leak in Fantasyland that was responsible for the ruination. Those events would be quickly forgotten with time. In fact, it was for quite the opposite reason. What Disney did was achieve a resounding success through the fabrication of a lie. Everything in Disneyland is artifice. Nothing here is real. The buildings are all in forced perspective. The rugged landscapes are all painted. You look into the eyes of a human and there’s nothing behind them but whirring machinery. Despite admitting nearly fifteen million people each year, the place is a ghost town of dead things and ideas, made to appear alive by the forces of consumerism. Socrates would have been much quicker to drink the hemlock if he could have known that over 2000 years later the pinnacle of popular culture would be an imitation of an imitation of an imitation.1

the opposite reason. What Disney did was achieve a resounding success through the fabrication of a lie. Everything in Disneyland is artifice. Nothing here is real. The buildings are all in forced perspective. The rugged landscapes are all painted. You look into the eyes of a human and there’s nothing behind them but whirring machinery. Despite admitting nearly fifteen million people each year, the place is a ghost town of dead things and ideas, made to appear alive by the forces of consumerism. Socrates would have been much quicker to drink the hemlock if he could have known that over 2000 years later the pinnacle of popular culture would be an imitation of an imitation of an imitation.1

Disneyland was nothing new, as fake museums and cities had long been in operation. But they were a negligible cultural curiosity, easily ignored by artists and intellectuals. America was the birthplace of Emerson and Thoreau. Its monuments were constructed by Frank Lloyd Wright, and its artistic currency printed by Mark Rothko. It was a place of brutal beauty. Brutal because it was real and sometimes ugly, beautiful because it was true. And what was this country’s beacon shining across the Atlantic, the first sight European travelers would encounter? Not the Statue of Liberty; it was an amusement park. A place where the tawdry and the fantastical became one and the same, where a million twinkling lights symbolized the promises of a generation, and where it didn’t have to be disguised as something it wasn’t to be beautiful.

had long been in operation. But they were a negligible cultural curiosity, easily ignored by artists and intellectuals. America was the birthplace of Emerson and Thoreau. Its monuments were constructed by Frank Lloyd Wright, and its artistic currency printed by Mark Rothko. It was a place of brutal beauty. Brutal because it was real and sometimes ugly, beautiful because it was true. And what was this country’s beacon shining across the Atlantic, the first sight European travelers would encounter? Not the Statue of Liberty; it was an amusement park. A place where the tawdry and the fantastical became one and the same, where a million twinkling lights symbolized the promises of a generation, and where it didn’t have to be disguised as something it wasn’t to be beautiful.

While Coney Island and its kind were already going into decline with or without Walt, what Disneyland did was cement the term “Theme Park” in the English lexicon. American culture’s interest in imitation wax museums and reconstructed ghost towns were probably destined to become historical footnotes, a minor postwar trend in escapism that offered little creative or artistic potential and was largely (and rightly) ignored by the intelligent public. But then Walt took the concept of faked, “hyperreal” environments and turned it into a national obsession by making it the key selling feature that differentiated Disneyland from the competition, and placed his park on a pedestal so high even the Soviet Premier couldn’t get it out of sight and threw a tantrum when he was denied entrance on his diplomatic visit. Disneyland set a new agenda for the amusement business for the remainder of the century such that the traditional amusement parks of old could never return unaffected by the themed fad. The public was hooked on the absolute fake.

Nowadays we’re given a false dichotomy to choose from. Either it’s an “amusement park”, and it’s just a collection of unadorned rides built on a piece of land for our instantaneous sensual gratification; or it’s a “theme park”, and it’s married to this specific idea Walt Disney had of making little fake worlds that were somehow better and happier than the real world. Although most parks fall along a gradient between the ideals, what the success of Disneyland (and, therefore, the Theme Park) did was eliminate the possibility of a third dimension by constricting our use of language to this two-dimensional plane. Towards one end of the axis are parks where everything must be disguised with artifice, and toward the other is the don’t-give-a-shit carnival park presentation. And if we’re to believe anything that Karl Marx tells us, it’s that our material reality tends to be limited by the language we have to represent it. Is it even possible to imagine a third park category that’s unbounded by both the vanilla-plain “amusement park” and the spectacularly fake “theme park”? Let’s try.

I’d argue that the Luna Parks, Dreamlands, and White Cities of yesteryear fit this third unnamable category. These were places where, relative to their time, attention to detail was no less meticulous than modern day theme parks. Beauty was just as important as the entertainment value, but the difference was the concept of “theming” was completely left out of the equation. What were these places themed to? An arbitrary few attractions theatrically recreated stories and history, but the emphasis was on the act of storytelling rather than simulating and enhancing lifelikeness. Advancing time a couple of decades, we also have the art deco splendor of a place like Denver’s Lakeside Park. It imitates nothing, the park symbolizes only itself, but it would also seem mildly insulting to file it among bread-and-butter amusement parks. What do we call these places?

Of course, the sad truth is that Lakeside is a small historical relic that’s not becoming fresher with age, and its relevance to the 21st century is only slightly more than a nostalgic time capsule. After Lakeside Park, World War II broke out which halted the aesthetic evolution of the business. And before these parks could reorganize, clean themselves up, and get going again, Disney came along with all the power of a media empire and redefined the aesthetic principles of the business such that these dirty parks would be left behind forever. If Luna Park hadn’t burned down and was still as dynamic and innovative as it had been 100 years ago, what would this “brutally beautiful” place look like today? Certainly nothing like the theme park imitation of Old Luna Park that’s currently sitting on that lot. But it’s hard to even imagine, so far has Disneyland and its line of successors redirected the evolutionary line of park design, that even our language has a hard time describing a park that does not fabricate mimesis. And I think we’re the worse off for that.

It’s ironic that for a place that was supposed to inspire the imagination of all who visited it, one of Disneyland’s biggest measures of success is how much it’s been copycatted by every other theme park built in the time since its debut. If you visit enough parks you begin to understand they’re all variations on the same theme, and that lineage can be traced all the way back to Anaheim. There must be a centerpiece icon, and the park must have big midways laid out in a radial or circular design (because crowds absolutely must be controlled along these routes). The entrance midway is always an exclusive collection of gift shops and food outlets, and you can make a good bet that one of the theme zones will involve some element of jungle adventure, children’s fantasy, science fiction, or the western frontier. And theme parks are now always viewed as a synergized distribution channel for some media outlet, with the most technologically advanced dark rides beholden to marketing the parent company’s most prized intellectual properties.

Disneyland is where the brutally beautiful America is sent to die, only to be resurrected in hagiographic form. Even when it imitates a natural or slightly unattractive part of the world, it looks too clean and perfect. Art is supposed to lead us to Truth, but there’s nothing real or truthful about “theming”. Heck, it’s not even a real word. Where were all the grammar Nazis on chat forums when people starting sticking the gerund onto a word that’s already a noun? Nevertheless, it seems to be the only word in our vocabulary that’s capable of describing the scenic things we find in Disneyland and its progeny, that doesn’t have the negative connotation of the next best alternative “imitation”.

When my external environment is “themed”, I go through my day in a state of perpetual cognitive dissonance, aware of the inherent phoniness while attempting to make believe it is real. If I don’t look in the direction the designers tell me to look or emote in the way I’m supposed to emote on cue, then the enjoyment is lost. Looking beneath the surface to discover the inner structural machination (literally and figuratively) is a vice instead of a virtue at Disneyland. Even if it seems a harmless game of make-believe, the encouragement of such an ethic should send a chill down the spine of anyone who wishes for a more enlightened society. Thankfully we all have self awareness and control over this cognitive dissonance, and it becomes a source of amusement. Notice how many people laugh when they’re confronted with a themed object that would be horrible if they actually believed it to be real. The unresolved mental conflict produces an emotional response that functions almost identically to humor.

As a result of this conflict, it seems that Disneyland is most appreciated by technophiles who put themselves with at least one foot outside the experiential realm of an attraction so they can look down on the rides and attractions from the same perspective as the designers. The buzzphrase for describing a Disney park is always “attention to detail”. Notice it’s not simply the detailing by itself, the praise is on the transitive act of designing and building an attraction, the attentive role of the Imagineers always beneath the surface of the parkgoer’s judgment. The best part of a Disneyland experience is when one is left wondering “how’d they do that?” I think every Disneyland aficionado secretly or not-so-secretly wants to play the role an Imagineer. Simple spectatorship always offers diminishing returns.

The problem with technophilia is that aesthetics are discussed is rather crass materialistic terms, where quality is usually linked to how expensive it looks, or how little mental work is required to convince one of a degree of realism. Story and mood become ciphers. There’s no intrinsic value to stories or styles; any form is acceptable as long as the attraction is done ‘correctly’. The compliments are rarely just for the richness and depth of the raw subjective experience by itself, although many hold a deep appreciation for the richness and depth of Disney’s pockets. “If this theme looks like it costs more than the competition, then it must be better a better theme!” It’s the nature of the hyperreal worlds of Disney to encourage this kind of appreciation, but I’m not certain if I personally have much use for it.

Before I get an influx of comments complaining that, A): I’m not the right person to criticize Disney because I don’t know how to simply immerse myself in the magic of the experience, B): speculating that I’m actually a closeted Disney fan in denial, or C): accusing me of holding Disneyland to a higher standard than I do for any other park, let me reply to these three comments right now.

A): Maybe. When other future enthusiasts were growing up on the Pirates of the Caribbean, I grew up on the Magnum XL-200. My first complete Disney experience didn’t happen until my junior year of college. Since then I have been incredibly fortunate to visit every Disney park outside the state of Florida in a little over a year.

In that year I’ve discovered something fundamental missing from these theme park experiences, something that could not be solved by more or better theming. Maybe it’s anhedonia. I’m not of the right psychology. I feel elated after being in the presence of a great “depressing” movie, and lousy after watching a Hollywood ending.

But I don’t think this proves me a curmudgeonly cynic. Quite the opposite.

To people who pay hundreds if not thousands of dollars to willfully “escape from reality” for the better part of a week, it is you I feel sorry for. Is life really that horrible? Is the rest of the world really that shitty? You really need to take a Disneyland vacation in the same way you need to take painkillers and antidepressants?

Those who leave behind their critical faculties in the car in order to maximize their enjoyment of Disneyland are the real cynics. Great art needs no shield from close scrutiny. In fact, its powers are only enhanced by critical analysis. If you need to cultivate some form of ignorance to enjoy something, no matter how minor or innocent that ignorance is, then you’ve already failed to achieve an authentically meaningful experience. I’m not saying I have any answers, but I do try to search for that authentic reality using the faculties I’ve been given.

Yes, I too wish upon a star that the world could always be a happy place. However, I don’t believe delusion is ever a good justification for happiness, no matter what the advertisements say.

Don’t worry. There’s still hope for Disneyland, which brings me to…

B): There is absolutely no truth that I’m a closeted Disney fan, because I’ll openly admit right now that I have a great time in their parks and I always look forward to returning. Their human resources and customer relations departments are perhaps the best I’ve ever witnessed in the amusement industry. After being aggravated again and again by bad management at both small family run and big chain regional parks, I cannot describe how refreshing it is to spend a day at a park where the management truly “gets it”. They keep lines moving at an obscene rate, and it is extremely rare that I notice a way in which capacity is not being maximized. I can always count on their employees (err, excuse me, “cast members”) to be efficient and courteous; no small feat considering most of them are pulled from college campuses.

Also, I’ve found the stereotype of Disneyland as a lawyer-heavy, nickel-and-dime happy, borderline fascistic universe to be untrue. In other parks if I try to take a picture where I’m arbitrarily not supposed to be standing or smuggle unsecured glasses on a ride, or violate any other of their 100 victimless rules, I get a screaming pimple-faced banshee sent after me. I am genuinely impressed and appreciative by how much common sense Disney has in establishing their park policies. They don’t hound you to use five dollar lockers at the entrance of every ride. You’re allowed to bring a camera on almost every ride, even many of the roller coasters. The FastPass system is completely free and egalitarian in design. Most impressive, where on-ride photos are present at the exit of an attraction, they do nothing to discourage people from snapping their own photo off the monitors, even though this quite obviously curbs the sale of prints, because they want their guests to have a take-home souvenir even if it doesn’t always mean more money in their pockets. They’re smart enough to understand that ‘clever’ profit-making schemes and constant legal defense maneuvers never achieves the same return on investment that a dedication to customer satisfaction and loyalty does.2

There are also the diversified attraction offerings, the always clean premises and facilities, the quality of craftsmanship, and the obvious huge amounts of research and effort that it takes to construct and maintain such a park. Like St. Peter’s Basilica, one is left in awe at the magnitude of this feat of human labor, so much so that one wonders if God had a hand in creating it. Both certainly attract a great many pilgrims seeking a deep religious experience worshipping their central deities, whether they be Jesus Christ or Mickey Mouse. But above all of this, there’s one reason in particular that I like Disneyland, which conveniently leads me to my final point.

C): I do hold Disney parks to a higher standard than any other park. Besides being the most expensive attractions-based parks worldwide, they’ve also got nearly unlimited creative resources and R&D funds, and have achieved huge economies of scale. Is it not unreasonable to expect more from the company that has always set the standard?

And that’s what I love most. Disneyland is the only place in the world where I can make all the miniscule, esoteric judgments about theme park theory without feeling guilty about bashing the best efforts of those who worked on it with limited means. When I praise other parks it’s usually against a background of limited expectations. If I judged every park at the same theoretical level I do for Disneyland, my reviews would all sound the same and it would be totally counterproductive. Disneyland thinks it is one of the happiest, most perfect places on earth, a place that’s supposed to inspire the imaginations of all who visit. I think that is probably true, as it inspires me to set my ideals at the highest level my powers of imagination can conceive. What is the most life-enriching experience we can conceivably create in the existing theme park format?

In fact, I would go so far to say this makes me one of the best fans Disneyland has, because I respect the talents of everyone involved in making these dreams a reality. Even the harshest of criticism is always in some form a compliment. It means the critic respects your innate potential at the very highest level. Anyone who says “I take Disneyland too seriously and should just enjoy it for what it is,” is making a much bigger insult to the Imagineers than they are to me. They say a theme park (amusement park, whatever we want to call it) can’t be an artistic masterpiece, that we should limit our expectations to disposable vacation entertainment. I say Disneyland can achieve this… and for every failure there are cases where they do indeed approach genius, and make me reconsider how much more perfect perfection can be made.

That’s why I’m going to Disneyland.

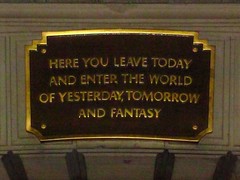

Our journey begins with an announcement that here we leave the world of today and enter the world of yesterday, tomorrow, and fantasy. Under the railroad tracks and through the rabbit hole we go, emerging on the other side in Main Street, U.S.A. This is an idealized recreation of Walt Disney’s childhood Missouri home, complete with City Hall, a fire station, cinema, penny arcade, trolley cars, and Abraham Lincoln. (Remember, this is the idealized version!) Pay close attention, not even space and time are quite what they seem. The buildings, you will notice, are all in forced perspective, meaning that the lower, ground-level floor is built at the standard 1:1 scale, while the second and third levels might be at 2:3 or 1:2, to give the illusion that the upper floors are further away than they really are. What’s more, the shop fronts are all angled slightly toward the Fantasyland castle, so that as we enter the park in the morning it appears as though we have an entire city to cross, while coming back the other way at night with sore and tired feet, Main Street has suddenly shrunken to a miniscule half-block. Even better than a magic trick, not only do the majority of visitors not know how it’s done, we don’t even realize an illusion

the shop fronts are all angled slightly toward the Fantasyland castle, so that as we enter the park in the morning it appears as though we have an entire city to cross, while coming back the other way at night with sore and tired feet, Main Street has suddenly shrunken to a miniscule half-block. Even better than a magic trick, not only do the majority of visitors not know how it’s done, we don’t even realize an illusion is unfolding before our very eyes!

is unfolding before our very eyes!

Nevertheless, there is a subconscious realization that somehow our bodies have been magnified, and that this smaller, better world is intrinsically linked to the manifestation of a bigger, better version of ourselves. It’s quite empowering and cathartic, which we need at this moment to stave off the emotional deflation of being just another head among the inrushing crowds. And what do we do with our newfound fantastical powers? Surely we won’t waste them

linked to the manifestation of a bigger, better version of ourselves. It’s quite empowering and cathartic, which we need at this moment to stave off the emotional deflation of being just another head among the inrushing crowds. And what do we do with our newfound fantastical powers? Surely we won’t waste them on the Disney Gallery, Main Street Cinema, or Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln? No, we’re in Disneyland,

on the Disney Gallery, Main Street Cinema, or Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln? No, we’re in Disneyland, so we’re going to partake in that one activity that makes us so smug to be an American: we shop!

so we’re going to partake in that one activity that makes us so smug to be an American: we shop!

Rows of mom-and-pop businesses invite our entrance, tantalizing us with caramelized sweets and playful knickknacks. There are no little Dickensian children pressing their noses against the glass in sad wistfulness in this universe. We’ve already paid our admission up front, so we know everything on display is designed exclusively for our own pleasures. It’s still a functioning Main Street, but one that’s been defanged from of the cruel bite of reality. We’re in a world where rules are only for games, and everything is make-believe. Our eyes are caught by make-believe advertisements, and we step over a make-believe curb to reach the make-believe doors, and inside we find a gigantically oversized emporium of make-believe goods and commodities, which we pay for with our make-believe money that’s burning a hole straight though our make-believe pockets.

so we know everything on display is designed exclusively for our own pleasures. It’s still a functioning Main Street, but one that’s been defanged from of the cruel bite of reality. We’re in a world where rules are only for games, and everything is make-believe. Our eyes are caught by make-believe advertisements, and we step over a make-believe curb to reach the make-believe doors, and inside we find a gigantically oversized emporium of make-believe goods and commodities, which we pay for with our make-believe money that’s burning a hole straight though our make-believe pockets.

Ah, I see what just happened! There is one rule within Main Street that remains unmodified from those governing the world outside of the Disney gates. It’s the law of capitalism. While the attention to detail is immaculate at transporting us back to 1908 in every slightest way, price inflation is the one remaining aspect that has not been adjusted for maximum lifelikeness. The facades invite us to pretend we’re still role-playing a game, even though they know and we know (and we know they know) that the Lincolns we’re exchanging over the counter are still more real than the Lincoln reciting Four Score and Seven Years Ago down the street. But we’re still playing the Disney game, and the first person to say aloud what isn’t make-believe ruins the fun for everyone. By the way, if that’s our working definition of “fun”, then it’s a game that Disneyland is very good at playing.

of the Disney gates. It’s the law of capitalism. While the attention to detail is immaculate at transporting us back to 1908 in every slightest way, price inflation is the one remaining aspect that has not been adjusted for maximum lifelikeness. The facades invite us to pretend we’re still role-playing a game, even though they know and we know (and we know they know) that the Lincolns we’re exchanging over the counter are still more real than the Lincoln reciting Four Score and Seven Years Ago down the street. But we’re still playing the Disney game, and the first person to say aloud what isn’t make-believe ruins the fun for everyone. By the way, if that’s our working definition of “fun”, then it’s a game that Disneyland is very good at playing.

Me, I’ll skip this pretend consumerism game for now. But I will come back to it at the end of the night, as I’ve got the start of a magnet collection from Disney parks around the world that I need to keep growing. First thing in the morning, I’ve got more immediate concerns in Adventureland.

Footnotes and Annotations

[1] For Socrates and Plato, art was condescendingly dismissed for imitating things found in the real world, which were already an imperfect imitation of the Ideal Form. Hence a theme park imitating art would be a third order imitation… and an incredibly dangerous place to have in the Republic, corrupting and deluding the population on a level of magnitude no Sophist could have even dreamed of.

[2] Then again, maybe it’s because they have so many lawyers they can be relaxed about some of their rules. Even if you were to get raped by Donald Duck they’ll always find a way to avoid liability, and then maybe file counter-suit too!

Another great report, I love your site and your analysis and I think part of the joy is that you can question or agree with it yourself and relate to the parks you feature,

Thanks for running such a great site,

Oliver

some disjointed brainfarts from me.

I personally do not understand your unease. I would argue that Disney offers subjective realism but Disney never forces you to accept it as a true reality because it never really tries to be the definition of the real world. Disney is a honey pot of effective representations but you dont have to buy into the fact that these representations are better than the real life counterparts. Thats ultimatly down to perception which is individual. In any example, a reflection will never be ‘real’ and we live by this and understand this even as children. The park boundaries may be infinate inside but they sure as hell are not from the outside. A blot of rainbow colours on an otherwise monochrome world creates a happy juxtoposition not because its better but just because its differnt. Its a convenient, capitalist coincidence that most people, passively accept Disneyland to be a better form of life in the same way that people accept the cast of friends to actually be friends. To me that just seems odd.

Alex, let me try to reconstruct your argument to make sure I understand you correctly. Stop me if I get anything wrong. Disney offers an alternative, more colorful reflection of the real world. It is up to each individual viewer to determine whether this intentional interpretation by the Imagineers is in fact “better” (but due to the nature of the park’s marketing and so on, most people incidentally do believe it is “better”). However, we do not assume the Disney environments to be in any way real. They are simply the equivalents of three dimensional paintings, artistically representative of the real world. It is through the comparison of the limited inner world of Disney with the infinite outer world that we experience a sense of happiness through the spectatorship of this more pleasing aesthetic.

I think to a degree you are correct, and that’s why, empirically, Disney is so successful. For me, the unease is generated by the fact that, unlike traditional art forms, there is no context, filter, or fourth wall in a theme park. The theme park lacks the media barrier that is constantly consciously reminding us that what we see isn’t “real” and is some other person’s representation of the real world. I.e., in photography and film you have a flat 2D screen and the cinematic montage; in sculpture you have the obvious use of a certain media (stone, plaster, wood, etc) and an external context (museum, city park, etc).

Theme parks occupy real space in real time, and the context is such that the environment attempts immersion on all sides, so that even if we always understand it as storytelling and representation (obviously no one ever believes theme parks to be literally true) we also understand these environments have a designed intentionality to make us believe as if these are authentic, spontaneous environments. Even in cases like Fantasyland, we’re supposed to believe the objects have different properties than they ordinarily do (“the Magic” isn’t quite as magical if we say “ah, this lovely scenery is made of Styrofoam and is only a few decades old”).

That is, for the themed environment to be effective, we have to want to believe there is something more transcendent beyond only being a themed environment. The problem is there isn’t transcendence and we know there isn’t, but we still want to believe there is to maximize our enjoyment of the design, so we go through the environment in a state of cognitive dissonance. It’s that internal dissonance within the viewer that’s the problem for me. It’s sort of like if a movie was filled with continuity errors and the crew in the field of view. We’re constantly made aware that what we authentically witness is something not 100% identical to what we wish we could be witnessing (that the film is fluidly unfolding before our eyes; some directors intentionally put ‘errors’ in their movies to make us aware of the subtextual metafilm and to create uneasy dissonance).

However, as with anything it’s more complex then that, and I’ll give examples later on where Disney does achieve an authentic experience that syncs with the artificial ‘make-believe’ experience.

I hope I adequately clarified my position enough such that you at least understand my argument better than I originally put forth. I really enjoy getting criticism back because it helps me figure out where problems are with my writing that will help me be a better communicator or maybe discover I’ve made an error in my argumentative position. Thank you, I hope this dialogue can continue.

Oliver, I’ll also take ordinary praise whenever I can get it. Thank you as well! 🙂

This analysis, particulary points B and C, basically sums up how I feel about Disney. I joke that my right brain doesn’t function; therefore, when I enter a Disney park, it is impossible for me to leave reality behind, not that I would have any interest in doing so. That being said, I enjoy Disney more than the average park-goer. Enjoying Disney analytically is easy, dispite what many people may think.

I have been to Walt Disney World four times, at ages 5, 9, 13, and 17, and still have feelings similar to your college-age-only experiences. (I’m 21 now.) The whole production facinates me, from the transcendent ride capacities to the simple truth that one will neve see two Mickeys at the same time, dispite the fact that they are everywhere.

I don’t really know where I was going with all of this, but please take the following as a serious suggestion and not just “ordinary praise.” Have you ever considered publishing your work as a compilation of essays, in book form? You should! The result would be well-received by the intelligent enthusiest community.

Adam, I like your point about how easy it is to enjoy Disney analytically. It’s fairly counter-intuitive given the image they have and how they sell their product, but I think you’re absolutely right that if you’re going to remain a Disney park fan into your teenage years, chances are you’ll be getting most of your kicks by marveling at the technical side of Disney. I bet they could make a real killing offering official, early morning “behind the scenes” tours of some of their rides like Busch Gardens Williamsburg does with their coasters.

Also, thank you for the book suggestion. That actually was originally part of my plan from before I even bought the domain name, but I want to get more material on top parks and coasters before I consider editing the material into anything that could be considered publishable. It’s good to hear there would be at least some demand for such a product!

I’d demand such a book, too. I love reading these reviews.

Thanks for saying so, Louis-Christophe. I’m really sorry it’s taken me so long to finish this series on Disneyland; I’m going to try to push Fantasyland out in the next couple of days. I finally had some free time over winter break to get a lot of writing done, but having done almost non-stop schoolwork, writing, and/or travel over the past two and a half years, my mind made an unwilled executive decision to sleep in and dick around with video games instead.