By Jeremy Thompson

Introduction

“Theme Park.”

“Amusement Park.”

In the public sphere these terms are often viewed as interchangeable synonyms, and many professionals working in the themed entertainment and amusement industries may be at a loss to describe the precise distinction between the two when questioned by peers, the public, or the press. For many, the similarities might easily overshadow the differences: both are usually ticketed, gated, and self-contained recreational destinations with a collection of mechanical amusement rides as their primary attendance driver. In terms of economics, they’re essentially substitute goods. Even professionals and fans who agree that there is a tremendous aesthetic distinction between theme and amusement parks, and who are quick to correct obvious misusages of these two terms in public forums, may still define each using very different personal criteria.

Nevertheless, if a general consensus among these advocates can be deduced, it’s typically that amusement parks represent locations with many relatively unadorned mechanical rides designed for a high sensation-seeking audience, while theme parks use their mechanical attractions within simulated fantastical or faraway environments, combining the sensation-seeking appeal of an amusement park with an element of storytelling to imbue these locations with special meaning (and create synergistic opportunities with whatever media company is sponsoring the park). However, such distinctions are often based on vague generalizations or intuition rather than a systemic analysis of the inherent properties to each, and many questions remain unresolved.

and many questions remain unresolved.

Is categorization a matter of hierarchies, whereby all theme parks are amusement parks but not all amusement parks are theme parks? Or is it more like a Venn diagram, with theme and amusement parks each occupying their own separate spheres that have overlapped? Is there a continual spectrum from one ideal form to the other, or are there too many separate sub-categorical branches that make the theme and amusement park dichotomy a false choice? And is the word properly spelled “themeing” or “theming,” assuming that either is correct?

The primary goal of this project is to answer the question: “What is a theme park?” especially as to how it relates to amusement parks and other location-based experiential entertainment. This project will first require a historical tracing of the conditions under which both terms were originally minted and how their usage evolved over time. It will then examine today’s “common” definitions of theme and amusement parks, and problematize several assumptions that are carried with these definitions. Next, it will propose a theoretical outline for codifying theme parks and amusement parks in terms of their different aesthetic qualities, primarily in terms of relationships between symbols. (This principled approach is favored because, as will be seen in the historical and problematization sections, a more empirical approach that statistically “checks off boxes” under each category will inevitably result in omissions and overlaps, given the complex, intertwined relationship between actual theme and amusement parks.) It will then use this theoretical framework to fill in gaps in the spectrum of location-based entertainment that fall outside or between these two most popular established categories, and finally this project will conclude with a few recommendations for proper usage of terms.

“What is a theme park?” especially as to how it relates to amusement parks and other location-based experiential entertainment. This project will first require a historical tracing of the conditions under which both terms were originally minted and how their usage evolved over time. It will then examine today’s “common” definitions of theme and amusement parks, and problematize several assumptions that are carried with these definitions. Next, it will propose a theoretical outline for codifying theme parks and amusement parks in terms of their different aesthetic qualities, primarily in terms of relationships between symbols. (This principled approach is favored because, as will be seen in the historical and problematization sections, a more empirical approach that statistically “checks off boxes” under each category will inevitably result in omissions and overlaps, given the complex, intertwined relationship between actual theme and amusement parks.) It will then use this theoretical framework to fill in gaps in the spectrum of location-based entertainment that fall outside or between these two most popular established categories, and finally this project will conclude with a few recommendations for proper usage of terms.

Origins

This lack of clarity on terminology likely originates from the fact that widespread adoption of each phrase evolved from distinct historical conditions that reflected the popular design trends of American amusements from different eras. These interrelated trends continued their evolution throughout the 20th century with little concern for semantic precision until recent decades as they grew into a major industry with a need for uniform representation. This segment will attempt to briefly trace the origins of “amusement” and “theme” parks, both as terms and as the places these terms represent.

What is today known as amusement parks have their origins in 18th and 19th century Europe, where they were known as “Pleasure Gardens.” Although they were largely inspired by (or repurposed from) the aristocratic gardens and park spaces from earlier centuries, these pleasure gardens were built with the explicit intent to provide entertainment for the growing middle class population fueled by the industrial revolution. Many gardens featured early mechanical amusement rides alongside other attractions such as concert halls, bandstands, picnic grounds, zoos, and exotic architecture and theatrical entertainment. Even in these early gardens, some of the prototypical amusement and theme park distinctions could be witnessed, with some gardens known for their follies and amusing pastimes (the earliest roller coasters have their origins in pleasure gardens as tobogganing hills for Russian and French aristocrats), while others were more focused on creating elaborate artificial landscapes that provided the opportunity for humans to feel themselves masters over the natural environment, causing nature itself to seemingly conform to enlightenment-era ideals and mythologies, even if only for a limited space. With time (and revolutions) these gardens came to shed some of their elite enlightenment-era values with more populist expressions of civic entertainment, but the basic concepts remained in place.

some of the prototypical amusement and theme park distinctions could be witnessed, with some gardens known for their follies and amusing pastimes (the earliest roller coasters have their origins in pleasure gardens as tobogganing hills for Russian and French aristocrats), while others were more focused on creating elaborate artificial landscapes that provided the opportunity for humans to feel themselves masters over the natural environment, causing nature itself to seemingly conform to enlightenment-era ideals and mythologies, even if only for a limited space. With time (and revolutions) these gardens came to shed some of their elite enlightenment-era values with more populist expressions of civic entertainment, but the basic concepts remained in place.

The concept of large public entertainment spaces eventually migrated across the Atlantic to Coney Island, New York in the mid-to-late 1800’s. Evolving from a collection of beach resorts, sideshows, and standalone amusements, the area eventually saw the debut of the first modern amusement park facility, Sea Lion Park, opened in 1895. It was distinguished as the first permanent park to enclose the property and charge one-price admission, as well as by its heavy emphasis on aquatic shows and mechanical rides, all features commonly associated with today’s amusement parks.

Steeplechase Park opened on a neighboring plot of land two years later, and to stay competitive Sea Lion Park was transformed in 1903 by new owners into Luna Park. Taking inspirational cues from World Expo design (notably the Colombian Exposition of 1893 and the Pan-American Exposition of 1901), Luna Park showcased a broad, centrally organized midway, fantastical exotic-Victorian architecture, dazzling light displays, and theatrical mechanical attractions such as it’s namesake, A Trip to the Moon, simulating a Vernian voyage to a paper machete moon with costumed actors playing the roles of Selenites. A third park opened its gates a year later as Dreamland, nearly as magnificent as its predecessor, although Luna Park remained the most iconic and set many of the standards for amusement parks in the decades to follow.

Steeplechase Park opened on a neighboring plot of land two years later, and to stay competitive Sea Lion Park was transformed in 1903 by new owners into Luna Park. Taking inspirational cues from World Expo design (notably the Colombian Exposition of 1893 and the Pan-American Exposition of 1901), Luna Park showcased a broad, centrally organized midway, fantastical exotic-Victorian architecture, dazzling light displays, and theatrical mechanical attractions such as it’s namesake, A Trip to the Moon, simulating a Vernian voyage to a paper machete moon with costumed actors playing the roles of Selenites. A third park opened its gates a year later as Dreamland, nearly as magnificent as its predecessor, although Luna Park remained the most iconic and set many of the standards for amusement parks in the decades to follow.

The term “amusement park” first appeared in print around the middle of the 1900’s decade, coinciding with the ascension of Coney Island from local playground to national jewel. However, the name “amusement park” was not the only generic descriptor that could be used for these parks during the initial golden age that lasted from roughly 1903 to 1929. There were several other generic names, including “trolley park” which was adopted due to the fact that many of these parks in cities around the country were owned and operated by trolley companies, and were built at the end of the lines to drive rail traffic during the weekends. Other parks simply adopted the monikers of their inspiration sources to easily communicate to their audiences what sort of experience they’d provide, and as a result hundreds of Coney Islands, Luna Parks, Dreamlands, White Cities, and Electric Parks sprouted up across the country and around the world. In fact, in several languages (French, Greek, Polish, Turkish, etc.) “amusement park” still translates as “luna park.” Such was the cultural impact of the Coney Island original.

Furthermore, these early parks still differed from today’s most generic definition of an amusement park as a permanent collection of rides on a plot of land. Although low-rent funfair parks have long existed, the landmark places that spawned imitators and popularized the concept of amusement parks were known for their neatly gardened park grounds and ornate architecture, and many featured theatrical and elaborately detailed scenic railways, cycloramas, and tunnels of love (often cited as predecessors to today’s dark rides and themed attractions) alongside their Ferris wheels and wooden coasters. Even the oft-cited staple of the amusement park, the carousel, in its original intent was essentially “themed” (if such retroactive nomenclature is relevant) to simulate medieval jousting and horse racing.

Furthermore, these early parks still differed from today’s most generic definition of an amusement park as a permanent collection of rides on a plot of land. Although low-rent funfair parks have long existed, the landmark places that spawned imitators and popularized the concept of amusement parks were known for their neatly gardened park grounds and ornate architecture, and many featured theatrical and elaborately detailed scenic railways, cycloramas, and tunnels of love (often cited as predecessors to today’s dark rides and themed attractions) alongside their Ferris wheels and wooden coasters. Even the oft-cited staple of the amusement park, the carousel, in its original intent was essentially “themed” (if such retroactive nomenclature is relevant) to simulate medieval jousting and horse racing.

Although the term had been around since the early 1900’s, it wasn’t until heading into the Great Depression in the late 1920’s that a growing majority of parks with mechanical attractions used the words “amusement park” in their names and advertisements to describe their business. By that point the economic downturn and war rationing left scarce resources to maintain the elaborate ornamentation that defined the “Luna Parks” and “White Cities” of old (nor was the nation’s war-weary mood as amenable to those park’s excessive Europeanized style); the mass market saturation of electric lighting robbed the “Electric Parks” of their novelty appeal; and with many trolley companies driven out of business as more Americans purchased automobiles, the term “trolley park” became an anachronism to the surviving parks they left behind.

Although the term had been around since the early 1900’s, it wasn’t until heading into the Great Depression in the late 1920’s that a growing majority of parks with mechanical attractions used the words “amusement park” in their names and advertisements to describe their business. By that point the economic downturn and war rationing left scarce resources to maintain the elaborate ornamentation that defined the “Luna Parks” and “White Cities” of old (nor was the nation’s war-weary mood as amenable to those park’s excessive Europeanized style); the mass market saturation of electric lighting robbed the “Electric Parks” of their novelty appeal; and with many trolley companies driven out of business as more Americans purchased automobiles, the term “trolley park” became an anachronism to the surviving parks they left behind. Absent of these alternative titles, “amusement park” was transformed from a description to a recognizable label by which all of these parks could be identified by. Characterized in the 40’s and 50’s by their relatively humble (some might say dirty) appearance and focus on simpler mechanical rides that could produce small but reliable profit margins, fast becoming a cultural relic in the age of television, the amusement park inherited a connotation with cheap entertainment that often persists to this day.

Absent of these alternative titles, “amusement park” was transformed from a description to a recognizable label by which all of these parks could be identified by. Characterized in the 40’s and 50’s by their relatively humble (some might say dirty) appearance and focus on simpler mechanical rides that could produce small but reliable profit margins, fast becoming a cultural relic in the age of television, the amusement park inherited a connotation with cheap entertainment that often persists to this day.

When Walt Disney announced his plans to build his Disneyland Park during the postwar economic boom of the 1950’s, the company realized that it needed to differentiate his product from the oft-perceived seedy and rundown amusement parks that speckled the country. Although in the first several years of operation Disneyland was simply “Disneyland,” an amusement park-like place unlike any other, the term “theme park” was eventually coined in the early 1960’s first in a newspaper article and then adopted as a piece of advertising copy to communicate to the public Disneyland’s distinctive brand of clean, organized simulated environments (or “lands” as they became known), built by Hollywood set designers and based on popular movie and fiction genres of the era. Like Luna Park, Disneyland took much of its inspiration from World Fairs and Expositions, as well as European pleasure gardens such as Tivoli Gardens in Denmark (itself inspired from older parks in France, England, and Italy). Also like Luna Park, Disneyland kick-started a wave of imitators that redefined the amusement business and even prompted changes to the vernacular. However, unlike Luna Park (which, despite its opulent façades, was located in a place once colloquially known as “Sodom by the Sea”) Disneyland rejected the maximalist, laissez-faire philosophy underlying the original Coney Island that gave it its somewhat tawdry sense of spectacle, and instead went with a clean, organized approach to design that emphasized continuity and cohesiveness.

Although Disney’s theme park was in many regards radically different from the cheap amusement parks of the era, it was not by itself a radical concept, but instead radical only in the way it mixed existing concepts together; in this case, the amusement park, the pleasure garden, and (perhaps most importantly) the living museum. While dioramas and other re-created spaces had been part of the original Coney Island parks, they were generally fairly limited and had proscenium-like boundaries, while Disney’s model drew more from large scale experiential history centers that re-created an entire community “as it would have appeared” in the day. Immersive, artificial environments were a growing popular trend in American museums and popular amusements through the 40’s and 50’s, spurred by a desire to create respectable family entertainment

Although Disney’s theme park was in many regards radically different from the cheap amusement parks of the era, it was not by itself a radical concept, but instead radical only in the way it mixed existing concepts together; in this case, the amusement park, the pleasure garden, and (perhaps most importantly) the living museum. While dioramas and other re-created spaces had been part of the original Coney Island parks, they were generally fairly limited and had proscenium-like boundaries, while Disney’s model drew more from large scale experiential history centers that re-created an entire community “as it would have appeared” in the day. Immersive, artificial environments were a growing popular trend in American museums and popular amusements through the 40’s and 50’s, spurred by a desire to create respectable family entertainment with pedagogic value, to bring a safe, romanticized, war-free vision of the world to American shores, as well as a desire to create a connection, however artificial they may be, with developing American historical mythologies as the country established itself on the world stage. Many of these prototypical theme parks were based around the nation’s revolutionary origins and western frontier, as could be seen in Michigan’s Greenfield Village, Virginia’s Colonial Williamsburg, or California’s Knott’s Berry Farm.

with pedagogic value, to bring a safe, romanticized, war-free vision of the world to American shores, as well as a desire to create a connection, however artificial they may be, with developing American historical mythologies as the country established itself on the world stage. Many of these prototypical theme parks were based around the nation’s revolutionary origins and western frontier, as could be seen in Michigan’s Greenfield Village, Virginia’s Colonial Williamsburg, or California’s Knott’s Berry Farm.

Disneyland’s very publicly visible success helped demonstrate the theme park as a sound business model, which consequently launch a renaissance of new regional parks built in the 1960’s and 1970’s, the majority of which were eager to self-apply the “theme park” label to distinguish their product as new and different from the original “amusement park” boom from the 1900’s to 1920’s. Some older parks even retroactively applied the term to themselves after Disneyland popularized the concept, such as Knott’s Berry Farm or the former Santa Claus Land in Indiana. The result of this wave of usage was that “theme park” became a similar generic term as “amusement park,” often intended to connote an image of the new and trendy rather than directly speak to the park’s content.

the majority of which were eager to self-apply the “theme park” label to distinguish their product as new and different from the original “amusement park” boom from the 1900’s to 1920’s. Some older parks even retroactively applied the term to themselves after Disneyland popularized the concept, such as Knott’s Berry Farm or the former Santa Claus Land in Indiana. The result of this wave of usage was that “theme park” became a similar generic term as “amusement park,” often intended to connote an image of the new and trendy rather than directly speak to the park’s content.

Gradually, however, parks began to discover what audiences responded to best and niche markets within the industry started to diverge. On the one side there was Disney’s theme park model, which throughout the 1960’s continued to emphasize story and immersive environments, further transitioning away from the living museum and decorated amusement park of its early years. Another major model developed which was the ride park, where huge, sensational roller coasters and other mechanical attractions spurred by technological innovations (especially prompted by the introduction of tubular steel-tracked looping roller coasters in the mid-1970’s) drew large crowds from regional suburban markets and could guarantee a reliable return on investment without the complicated theatrical elements required by a Disneyland-type experience. In response to these divergent styles, the distinction between theme and amusement parks had fairly well solidified by the 1980’s and 90’s, although confusion continues to remain to this day.

model, which throughout the 1960’s continued to emphasize story and immersive environments, further transitioning away from the living museum and decorated amusement park of its early years. Another major model developed which was the ride park, where huge, sensational roller coasters and other mechanical attractions spurred by technological innovations (especially prompted by the introduction of tubular steel-tracked looping roller coasters in the mid-1970’s) drew large crowds from regional suburban markets and could guarantee a reliable return on investment without the complicated theatrical elements required by a Disneyland-type experience. In response to these divergent styles, the distinction between theme and amusement parks had fairly well solidified by the 1980’s and 90’s, although confusion continues to remain to this day.

Much of this confusion stems from the fact that many of these parks represent a mix of features commonly attributed to either theme or amusement parks, which has made many efforts to categorize the two extremely difficult. Most modern amusement parks display some theme park characteristics, and vice versa. Although amusement and theme parks are not synonymous, the sheer number of facilities that overlap the two concepts (and the scarcity of “purebred” examples) makes it so that either these terms could be reasonably applied to a majority of large parks around the world.

Cincinnati’s Kings Island, which opened under the Taft Broadcasting Company in 1972, was a prime example of this mixed content. It borrowed heavily from Disneyland-style themed design, complete with an international version of Main Street anchored by a centerpiece Eiffel Tower replica, and was surrounded by proxies of Adventureland, Frontierland, and a Fantasyland-inspired Hanna-Barbera area. (Not coincidentally both Anaheim and Cincinnati

Cincinnati’s Kings Island, which opened under the Taft Broadcasting Company in 1972, was a prime example of this mixed content. It borrowed heavily from Disneyland-style themed design, complete with an international version of Main Street anchored by a centerpiece Eiffel Tower replica, and was surrounded by proxies of Adventureland, Frontierland, and a Fantasyland-inspired Hanna-Barbera area. (Not coincidentally both Anaheim and Cincinnati parks shared talent, including art director and production designer Bruce Bushman.) However it also opened with a large signature area known as “Coney Mall” that replicated the look and feel of traditional amusement parks, particularly the famous Coney Island Ohio park formerly located in Cincinnati, and featured a large, elegant racing wooden roller coaster named The Racer. Following an appearance in an episode of the Brady Bunch in 1973, The Racer launched a rebirth in classic wooden roller coaster design, once again becoming a staple of nearly every regional park across the country regardless of whether they labeled themselves a theme or amusement park. Kings Island’s parent company was later acquired by Paramount Pictures, which brought Universal Studios-style movie attractions to the park alongside the Racer, as well as several large, relatively undecorated thrill rides.

parks shared talent, including art director and production designer Bruce Bushman.) However it also opened with a large signature area known as “Coney Mall” that replicated the look and feel of traditional amusement parks, particularly the famous Coney Island Ohio park formerly located in Cincinnati, and featured a large, elegant racing wooden roller coaster named The Racer. Following an appearance in an episode of the Brady Bunch in 1973, The Racer launched a rebirth in classic wooden roller coaster design, once again becoming a staple of nearly every regional park across the country regardless of whether they labeled themselves a theme or amusement park. Kings Island’s parent company was later acquired by Paramount Pictures, which brought Universal Studios-style movie attractions to the park alongside the Racer, as well as several large, relatively undecorated thrill rides.

The Six Flags theme parks have a similar mixed heritage, beginning life strictly as theme parks devoted to local and regional American history (debuting in Texas, with later parks opening in Georgia and St. Louis). The original “six flags” referred to the different national flags flown over the state of Texas, which has different themed areas for Spain, France, Mexico, the Republic of Texas, the United States, and the Confederate States. Later in life, particularly after an acquisition by Time-Warner, the parks then transitioned to include both roller coasters and Warner Bros. movie properties, while a later acquisition by Premier Parks saw capital expenditures focused on high-profile roller coasters with relatively minimal attention paid to cohesive theme design. Today it’s not uncommon for a Six Flags amusement/theme park to contain several old-timey

The Six Flags theme parks have a similar mixed heritage, beginning life strictly as theme parks devoted to local and regional American history (debuting in Texas, with later parks opening in Georgia and St. Louis). The original “six flags” referred to the different national flags flown over the state of Texas, which has different themed areas for Spain, France, Mexico, the Republic of Texas, the United States, and the Confederate States. Later in life, particularly after an acquisition by Time-Warner, the parks then transitioned to include both roller coasters and Warner Bros. movie properties, while a later acquisition by Premier Parks saw capital expenditures focused on high-profile roller coasters with relatively minimal attention paid to cohesive theme design. Today it’s not uncommon for a Six Flags amusement/theme park to contain several old-timey buildings collectively labeled on the map as something like “Colonial Square” or “Lickskillet,” which will double as the showcase plaza for a new, brightly colored hypercoaster named something like “Goliath,” and located next to a semi-immersive themed environment for DC Comics. In cases such as this it’s impossible to categorize an entire park as strictly a theme or amusement park; the most that can be done is to identify which layers or components of these parks are better sorted into either category.

buildings collectively labeled on the map as something like “Colonial Square” or “Lickskillet,” which will double as the showcase plaza for a new, brightly colored hypercoaster named something like “Goliath,” and located next to a semi-immersive themed environment for DC Comics. In cases such as this it’s impossible to categorize an entire park as strictly a theme or amusement park; the most that can be done is to identify which layers or components of these parks are better sorted into either category.

The conclusion of this historical review is that neither the term “amusement park” nor “theme park” has a clear origin that precisely describe the types of attractions they represent. Today’s commonly mixed, overlapping usages of the two terms stem from a history in which the meaning of these terms was even more muddled and murky, and attempts to create a clear, precise distinction between the two are only a fairly recent phenomenon. In many regards both terms were created under similar conditions: as ways to differentiate the new parks of their respective eras from the old, and the collection of design methods that became associated with each term tended to reflect popular business models of the time rather than fit to a neatly organized theory.

This isn’t to suggest that there’s no significant distinction between the two forms beyond subtleties in marketing jargon. To the contrary, there is a huge stylistic gulf that can make amusement and theme parks two entirely different media for entertainment and creative expression. However, making that distinction clear will require a more theoretical approach rooted in aesthetics, rather than a historically oriented approach rooted in statistics. The purpose of such a categorical understanding of experiential entertainment shouldn’t be to simply draw arbitrary boundaries that create limiting claims such as, “an average amusement park contains 4.8 roller coasters, 1.8 carousels, 1.3 Ferris wheels, etc.” Theme, amusement, and other related entertainment forms still have tremendous room for creative growth, and a critical examination of what makes these parks such uniquely singular aesthetic experiences will help future designers better understand their craft.

Problematizing the Divide

For many fans and professionals in the world of themed entertainment, discussing the difference between theme and amusement parks is frequently regarded as a problem of public relations. If the public can be properly educated about the difference between theme and amusement parks, then the misusage of terminology will cease and the problem will go away. Even if there’s room for debate over how to categorize certain specific parks that mix elements from the theme and amusement categories, the general defining elements of each category are assumed to be relatively concrete and immutable. An amusement park is a collection of rides on a park ground with shops and other supporting facilities, while the theme park takes the foundation of an amusement park and overlays it with immersive environmental story worlds and characters.

However, this common approach to the divide between theme and amusement parks introduces several problems. Firstly, it presents a potential fallacy of false choice. Given the somewhat circumstantial origins of the terms “amusement park” and “theme park,” the question should immediately be raised of whether these really are the only two categories of parks that exist within location-based entertainment, or if there are more categories that simply didn’t have as good a marketing team behind them when it came time to mint new linguistic currency. I will propose in a later segment that there are indeed distinct missing categories that are often improperly grouped under theme or amusement labels; and in fact that theme and amusement parks are better thought of as subsets of larger categories that include numerous other related types of design.

Additionally, the current theme and amusement park dichotomy introduces a hierarchical structure to the categorization that designates theme parks as inherently more complex, more creative, or even categorically “better” (depending on who’s interpreting) than amusement parks. As the argument often goes, an amusement park plus themed design equals a theme park; theme parks are therefore “above” amusement parks and represent a higher-order level of quality. Because theme parks are highly organized to maintain a cohesive narrative structure, it reasons to follow that amusement parks must represent an opposing tendency to be disorganized or visually chaotic by comparison. There have been several recent opinion pieces comparing these two categories that describe amusement parks with similarly unflattering language. One notable example, Margaret J. King and J.G. O’Boyle stated in the essay The Theme Park: The Art of Time and Space, “A theme park without rides is still a theme park: an amusement park without rides is a parking lot with popcorn.” (7) This was among many other statements suggesting that amusement parks are limited experiences that are less than an artform in comparison to theme parks.

This hierarchic classification generally ignores the complexities of amusement park design and requires inventing an “amusement park” stereotype resembling traveling carnivals that has little empiric support when surveying actual amusement parks of similar size and scale to their theme park counterparts. Many large modern amusement parks share with theme parks an emphasis on attractive and artistic presentation, carefully managed sightlines when considering attraction placement, and crafting emotional sequences for guests that follow narrative-like structures, but none of which is done for the purpose of creating a fictional story-world to parallel or cover over the park-going experience. This suggests that there’s a unique language to amusement park design that’s separate from theme park design, and they both deserve to be represented separately in a survey of design theories. Dismissing amusement parks as inferior, incomplete theme parks seems a bit like dismissing popular music as an inferior, incomplete attempt at classical music.

Hierarchical categorization also has the tendency to become a self-fulfilling prophecy; parks with lower budgets frequently receive the amusement park label as a way to denote that their audience is from a lower socio-economic rung, and a majority of both new park projects and amusement parks that are looking to upgrade the quality of their experience are more frequently turning to themed design as a way to easily prove to guests that theirs is the more expensive product. Wanting to avoid this negative label, there are an increasing number of instances of cheap, patchwork themed design elements being overlaid on classic amusement parks in misguided attempts to “class up” the park, which have arguably compromised the park’s original authentic design. A traditional, rustic countryside park might suddenly begin to sport fiberglass pirate-themed props under the misguided belief that any form of simulacra is an improvement to the guest experience over no simulacra; and then the small park wonders why comparisons to world class theme parks is always negative. In many cases, the theme and amusement park distinction has become coded for a distinction between the middle and lower class, which become particularly problematic when it’s also inferred that one is of greater cultural and social merit than the other. Disney or Universal-style hyperreal themed design is far from the only kind that can be applied to a world-class park, even if their immense brand recognition has meant that most world-class parks have also adopted this style looking to emulate their success.

It’s true that theme parks on average are more expensive and technically complex than amusement parks, but this isn’t necessarily because of an innate aesthetic hierarchy (in which amusement parks are just theme parks missing theming), but simply from the economic reality that today’s consumer preferences and design trends allows for more capital to go to themed projects. It also has to do with the fact that the popular hyperreal style of themed design requires many more resources to properly realize, in the same way a CGI-laden science fiction fantasy film requires a bigger budget than a cinéma vérité character melodrama. Just as these different styles of filmmaking shouldn’t be misconstrued as falling under an aesthetic hierarchy, neither should theme and amusement parks be considered to be part of their own hierarchy; amusement parks offer rich creative opportunities if designers and fans are willing to look closely.

A final problem facing the topic “what is a theme park,” is to consider the question: “What is a theme?” Theme is a literary term, and while it might seem appropriate given that theme park designers share much in common with storytellers in other media, there’s a frequent disconnect between this word’s application in amusement industry jargon and its use in broader contexts. This lack of semantic precision can pose additional challenges to the task of defining a theme park.

Theme is an abstract noun. It refers to other abstract nouns: the ideas, motifs, or values that unify a work of art and allows for meaningful interpretations by the viewer. A theme is typically stated as something like “the love of life,” “the spirit of adventure,” or “the danger of unchecked ambition.” However, when referring to a theme within a theme park context, the colloquial usage typically reifies these subjects into concrete nouns: pirates, space travel, Harry Potter, etc. These aren’t “dramatic themes” in the literary tradition of the word but rather “tag themes” that indicate a particular setting or subject matter, similar to the theme of a prom or birthday party.

This reification of “theme” may be taken one step further so that the word refers directly to the physical props, sets, and decorations that compose a theme park. This is done by transforming the word into the verb form “to theme,” (e.g. “The designers will theme this area to nautical exploration,”) from which is derived the noun form “theming,” (e.g. “This fake rockwork and wood panel theming is very realistic,”) and adjective form “themed,” (e.g. “Now we’re walking through the western-themed area of the park”). Although these usages have become widespread within industry jargon and among fans, there are still several unresolved issues with their continued use. Firstly, the majority of dictionary usage panels continue to reject these forms derived from the verb “to theme.” The word “theming” also becomes overly malleable to encompass nearly any form of decorative element in a park, thus narrowing the useful distinction between theme and amusement parks, since virtually all contemporary public spaces include some form of ornamentation that could be considered “theming.” Additionally, by redefining a valuable abstract literary term to mean something more concrete, it risks robbing theme parks of a sense of their artistic merit. Imagine if theme park fans discussed a park’s themes in the same way that a literary critic would discuss a new novel’s? Reconciling and organizing this nomenclature is another necessary step for defining a theme park.

The next section will address the underpinnings of aesthetic theory that will attempt to offer an admittedly incomplete solution to the question, “What is a theme park?” Bearing in mind the problems addressed in the preceding paragraphs, this solution will view theme and amusement parks as two distinct aesthetic categories, albeit categories that can be endlessly mixed along a spectrum. Later, it will also consider the possibility of additional categories of parks that are missing from the current amusement and theme park division.

Theme Parks as Stories, Symbols, and Series

Theme parks sell stories. Stories are their brand. They are places where an audience goes to experience a story in a living environment, where the forth wall is removed and patrons live completely within the diegetic construct of the storyteller’s world. This immersion into story is one of the factors that allow theme parks to continue to resonate for twenty-first century audiences, and is typically considered the defining feature that sets them apart from amusement parks, where such story worlds are absent. This association with story is unsurprising given the medium’s strong historical ties to the film industry, with Disney and Universal Studios continuing to be flag bearers for the theme park identity to this day. Although many theme parks are renown for their collection of mechanical rides, their intended function is usually different than in an amusement park. While in an amusement park the ride is generally an “ends to entertainment” in itself, in a theme park rides are treated as tools to a reach a different end – to tell a story – where ride vehicles function either as characters or props within the story (e.g. a runaway mine train escaping from an abandoned mine), or as a means to establish an invisible third person perspective (e.g. an omnimover dark ride that functions as a panning camera lens).

given the medium’s strong historical ties to the film industry, with Disney and Universal Studios continuing to be flag bearers for the theme park identity to this day. Although many theme parks are renown for their collection of mechanical rides, their intended function is usually different than in an amusement park. While in an amusement park the ride is generally an “ends to entertainment” in itself, in a theme park rides are treated as tools to a reach a different end – to tell a story – where ride vehicles function either as characters or props within the story (e.g. a runaway mine train escaping from an abandoned mine), or as a means to establish an invisible third person perspective (e.g. an omnimover dark ride that functions as a panning camera lens).

That said, story is also one of the most frequently misunderstood terms associated with theme parks. Story both defines what a theme park is in a way that an amusement park is not; yet it can also confuse an understanding of how theme parks actually function. The word “story” typically implies narrative storytelling, which is a representation of characters and settings within a sequence of events (or plot) by a narrator that assumes a singular fixed point of view (usually described as taking place in the first, second, or third person).

In truth, a theme park, by its permanent physical presence and free exploratory design, is actually a fairly difficult medium for traditional narrative storytelling. Such narratives in a theme park are typically achievable only in standalone theatrical attractions that force guests along a single, linear point of view for the duration of the experience. Some theme parks, most notably the Universal Studios parks, do attempt to place a large emphasis on narrative storytelling by employing a fairly neutral “studio backlot” appearance for the majority of the park space to link standalone attractions that contain a relatively complex narrative arc that begins and ends at the show building walls. Another common solution to narrative storytelling in theme parks takes the form of “book report” dark rides based on a popular story, in which key scenes are stitched together to create a summary of the source material, and are typically based on familiar media properties that use the audience’s prior knowledge of the brand’s setting and characters to help fill in narrative gaps that would otherwise be difficult to convey in a three minute experience.

contain a relatively complex narrative arc that begins and ends at the show building walls. Another common solution to narrative storytelling in theme parks takes the form of “book report” dark rides based on a popular story, in which key scenes are stitched together to create a summary of the source material, and are typically based on familiar media properties that use the audience’s prior knowledge of the brand’s setting and characters to help fill in narrative gaps that would otherwise be difficult to convey in a three minute experience.

However, many theme parks lack clearly defined narratives, whether in individual attractions or across the entire park, and in such instances “story” can have very different implications. Even those parks that do rely heavily on traditional storytelling in their dark rides and media attractions might have large themed plazas outside these attractions which have a more ambiguous relationship to narrative storytelling. These forms of stories might be labeled variously as “environmental storytelling” (i.e. immersing the visitor in a rich, unfamiliar sense of place that acts as a stage for the patron’s imagination to create their own back stories), “interactive storytelling” (i.e. the audience participates in creating their own narrative stories within a set of parameters provided by the author using methods typical of augmented reality games), or “forensic storytelling” (i.e. the visitor happens upon a scene and is forced to re-create the story based on information obtained from props and messages left behind by absent characters; exploratory attractions such as the Swiss Family Treehouse or Tom Sawyer Island

dark rides and media attractions might have large themed plazas outside these attractions which have a more ambiguous relationship to narrative storytelling. These forms of stories might be labeled variously as “environmental storytelling” (i.e. immersing the visitor in a rich, unfamiliar sense of place that acts as a stage for the patron’s imagination to create their own back stories), “interactive storytelling” (i.e. the audience participates in creating their own narrative stories within a set of parameters provided by the author using methods typical of augmented reality games), or “forensic storytelling” (i.e. the visitor happens upon a scene and is forced to re-create the story based on information obtained from props and messages left behind by absent characters; exploratory attractions such as the Swiss Family Treehouse or Tom Sawyer Island at Walt Disney World’s Magic Kingdom are prime examples of this type of non-narrative storytelling). An investigation into the different ways “story” can be applied in a theme park, especially those that lack narrative in the traditional sense, would be endlessly fascinating (and quite possibly endless), and a topic for a different paper. Although “story” is a useful tool for communicating what a theme park is to the general public, it’s also an extremely broad concept with too many special cases and exemptions to make a fine-tuned distinction between theme and amusement parks, many of which share some of the more abstract forms of story.

at Walt Disney World’s Magic Kingdom are prime examples of this type of non-narrative storytelling). An investigation into the different ways “story” can be applied in a theme park, especially those that lack narrative in the traditional sense, would be endlessly fascinating (and quite possibly endless), and a topic for a different paper. Although “story” is a useful tool for communicating what a theme park is to the general public, it’s also an extremely broad concept with too many special cases and exemptions to make a fine-tuned distinction between theme and amusement parks, many of which share some of the more abstract forms of story.

Instead, theme parks can perhaps best be conceptualized in terms of “symbols” and “series.” A story at its most basic level is, after all, a series of symbols, whether they’re words arranged on a page or moving images sequenced on a screen. But symbols and series are also inclusive of many unique elements of theme park design that “story” might miss, and are less awkward in describing a physical location, lacking some of the strict temporal requirements of narrative. Additionally, because all forms of location-based entertainment, including both amusement and theme parks, use symbols and series to entertain and communicate with their visitors, identifying the different ways that these concepts can be applied will help make distinctions between the two types of park while avoiding reductive hierarchical structures that define amusement parks in terms of what they’re “missing” from theme parks.

a series of symbols, whether they’re words arranged on a page or moving images sequenced on a screen. But symbols and series are also inclusive of many unique elements of theme park design that “story” might miss, and are less awkward in describing a physical location, lacking some of the strict temporal requirements of narrative. Additionally, because all forms of location-based entertainment, including both amusement and theme parks, use symbols and series to entertain and communicate with their visitors, identifying the different ways that these concepts can be applied will help make distinctions between the two types of park while avoiding reductive hierarchical structures that define amusement parks in terms of what they’re “missing” from theme parks.

Symbols represent one of the most distinguishing characteristics of theme parks, and are mostly contained in the concept of “theming” or a “themed object” – the latter is a slightly more academic-sounding variant of “theming” that I prefer to use for the way the concept is located in a single, specific concrete object, and thus emphasizes the bricks and mortar that compose a theme park (unlike “theming” which, among other usage issues, takes a verb form that makes the concept seem more abstract and transient than it really is). A themed object, in essence, is a symbol for a concrete object that’s manifested in a similar concrete form. For example, consider an audio-animatronic crocodile (ever a theme park staple) as a symbol contained in a physical object: physically it’s just a mechanical mass of painted latex rubber concealing the metal superstructure and hydraulic parts that give the figure its animated life, but it also acts as a symbol for a real crocodile, specifically for the way that it recalls many of the emotional responses one would associate with a live croc encounter: fear, disgust, curiosity, admiration, and so on.

A themed object, in essence, is a symbol for a concrete object that’s manifested in a similar concrete form. For example, consider an audio-animatronic crocodile (ever a theme park staple) as a symbol contained in a physical object: physically it’s just a mechanical mass of painted latex rubber concealing the metal superstructure and hydraulic parts that give the figure its animated life, but it also acts as a symbol for a real crocodile, specifically for the way that it recalls many of the emotional responses one would associate with a live croc encounter: fear, disgust, curiosity, admiration, and so on.

However, the symbolism of a themed object is perceived differently from symbolism in more traditional dimensional arts. For example, a statue might be symbolic of the person or thing it represents, but it’s still perceived as is; a statue is never intended to be confused with its living, breathing referent. A themed object, on the other hand, is perceived through a mechanism of substitution rather than representation. With a combination of lifelikeness and suspension of disbelief, the audience witnesses not a mechanical representation of a crocodile, but a real crocodile virtually indistinguishable from its biological brethren. A themed object is a symbol that attempts to replace that which it symbolizes. It’s a copy that substitutes itself for the original; a tangible simulation of the real world within a faked hyperreal world, and it wants viewers to believe, if only for a split second, that the fictional construct before them is authentic.

For example, a statue might be symbolic of the person or thing it represents, but it’s still perceived as is; a statue is never intended to be confused with its living, breathing referent. A themed object, on the other hand, is perceived through a mechanism of substitution rather than representation. With a combination of lifelikeness and suspension of disbelief, the audience witnesses not a mechanical representation of a crocodile, but a real crocodile virtually indistinguishable from its biological brethren. A themed object is a symbol that attempts to replace that which it symbolizes. It’s a copy that substitutes itself for the original; a tangible simulation of the real world within a faked hyperreal world, and it wants viewers to believe, if only for a split second, that the fictional construct before them is authentic.

Thus, a theme park can partly be defined as a place that is significantly composed of theming or themed objects – in either case, symbols – that cause a displaced sense of location. The referent for the theme park symbol is almost always external to the park, meaning that a theme park requires a certain amount of cultural literacy, usually about distant environments and time periods in order to be properly read and understood. If the referent is meaningless to a viewer, so too is the themed object. This requirement is also perhaps why most theme parks tend to skew towards relatively high concept themes or familiar brands whose symbols can be easily read by a majority of audiences.

Some of these external referents might be real places; for example, Disneyland’s Main Street, U.S.A. consists almost entirely of symbols that have some referents in American architecture, even if they’re from outside the Midwest. Others might be based entirely

Some of these external referents might be real places; for example, Disneyland’s Main Street, U.S.A. consists almost entirely of symbols that have some referents in American architecture, even if they’re from outside the Midwest. Others might be based entirely in fiction, such as Universal Studio’s Wizarding World of Harry Potter that contains multitudes of symbols alluding to the imaginative worlds of the popular novels and films. Others are murkier amalgamations of symbols that reference broader cultural trends and ideals rather than any specific objects located in the real world, such as the retro-futurist design found in Disney’s Tomorrowlands. And some theme parks, especially those with environments presented predominantly through architecture, might be so identical to their source that they venture into the thorny grey areas where symbols and their referents begin to overlap (i.e. If one pagoda is constructed with the same materials and techniques as every other pagoda, is there a meaningful difference if it’s located in Tokyo or Florida?).

in fiction, such as Universal Studio’s Wizarding World of Harry Potter that contains multitudes of symbols alluding to the imaginative worlds of the popular novels and films. Others are murkier amalgamations of symbols that reference broader cultural trends and ideals rather than any specific objects located in the real world, such as the retro-futurist design found in Disney’s Tomorrowlands. And some theme parks, especially those with environments presented predominantly through architecture, might be so identical to their source that they venture into the thorny grey areas where symbols and their referents begin to overlap (i.e. If one pagoda is constructed with the same materials and techniques as every other pagoda, is there a meaningful difference if it’s located in Tokyo or Florida?).

It’s from here that the second part of the equation defining a theme park can be added: the series. After all, physically manifested symbols, even those that are hyperreal and meant to substitute for the real thing, make up a vast portion of the modern landscape and are found in countless places that would never be considered a theme park, from restaurants to shopping malls to children’s bedrooms. What sets theme parks apart is the way that those physical symbols are placed in series, allowing them to control meaning and manipulate identity in a way that isolated symbols are unable to do. Series are what gives theme parks their distinctive “story” quality, in which the brain processes information in a sequential order that allows for the reveal of key emotional moments. However, while all narratives are series, not all series are manifested as narratives. John Hench, former senior vice president of Walt Disney Imagineering, articulated the concept of the series as it applies to theme parks in the essay “Disneyland is Good For You,” from an interview with New West Magazine in December 1978:

“[Disneyland] is easily understandable when you think of it like a film and how identity is controlled in a film. Identity is a figure-ground relationship: Scene five takes its identity from scenes one, two, three and four. If you put scene five against that background, you understand it, but if you just dropped it in the audience’s laps they wouldn’t know what was going on. […] One side of Main Street is aware of the other side. It was planned for this very effect, and who else but motion-picture people, who design sets, could do it? Walt understood the relation between scene one and scene two, he knew how to identify something and how to hold the identity due to something the Germans call gestalt. Nothing has an identity of its own until it’s related to something else. If you can control that relation, you can control identity. You can use images in a literate way.” (16)

Although series can be used to describe temporal relationships that make up narrative in theme parks and especially dark rides or shows, series also represent the way that a themed environment can establish identity or even tell a story through purely spatial relationships. Hench’s words are perhaps most evident in the entry sequence to the most noteworthy project he was involved in, the original Disneyland and Main Street U.S.A. First of all, consider how the relationship between a series of images or symbols can be used to control identity. The series on Main Street is used to establish a fixed sense of time and place: A City Hall is followed by a Fire Department, then a row of commercial establishments with typical Victorian architectural details including a Penny Arcade and Nickelodeon theater, and numerous gas lamps and horse-drawn buggies are interspersed between these elements. When taken individually, these symbolic objects could be interpreted in a number of different ways, but when taken together as a series, the relationship between these objects and the fact that they all share a common category creates a single, unified identity:

in the entry sequence to the most noteworthy project he was involved in, the original Disneyland and Main Street U.S.A. First of all, consider how the relationship between a series of images or symbols can be used to control identity. The series on Main Street is used to establish a fixed sense of time and place: A City Hall is followed by a Fire Department, then a row of commercial establishments with typical Victorian architectural details including a Penny Arcade and Nickelodeon theater, and numerous gas lamps and horse-drawn buggies are interspersed between these elements. When taken individually, these symbolic objects could be interpreted in a number of different ways, but when taken together as a series, the relationship between these objects and the fact that they all share a common category creates a single, unified identity: a turn-of-the-century American town. This type of series might also be called a “stratified series,” referring to the stacked accumulation of details in a particular area that create a consistent identity of time and place.

a turn-of-the-century American town. This type of series might also be called a “stratified series,” referring to the stacked accumulation of details in a particular area that create a consistent identity of time and place.

Especially important to note is that this stratified series is both complete and exclusive. Not only does each symbol complement each other in a way that creates a complete dimensional image of Americana, but they’re also arranged to deliberately exclude any visual information that isn’t part the primary series. This principle of exclusivity in theme parks is what often lends to them being called “immersive,” as there are no (or, at least, as few as possible) signals that contradict the dominant series and thus break the illusion that the spectator is located in a fictional environment outside the park. Exposed mechanical ride hardware is a typical example of common visual intrusions in a theme park’s stratified series (unless the area’s theme would make sense having mechanical rides in it, such as Disney Animal Kingdom’s vintage roadside Americana inspired Dinoland U.S.A.), but it also includes other anachronistic details (contemporary pop music playing in an area that’s supposed to represent the distant past, for example) or structures visible from outside the theme park’s berm (hotels or skyscrapers visible over the horizon in the middle of what’s supposed to be a remote tropical outpost). In many transition zones between themed areas, buildings or props visible from both locations are often designed to be reasonably convincing as part of either series. (The nondescript planks of a wooden shack located between a western frontier area and a jungle adventure area, for example.)

Especially important to note is that this stratified series is both complete and exclusive. Not only does each symbol complement each other in a way that creates a complete dimensional image of Americana, but they’re also arranged to deliberately exclude any visual information that isn’t part the primary series. This principle of exclusivity in theme parks is what often lends to them being called “immersive,” as there are no (or, at least, as few as possible) signals that contradict the dominant series and thus break the illusion that the spectator is located in a fictional environment outside the park. Exposed mechanical ride hardware is a typical example of common visual intrusions in a theme park’s stratified series (unless the area’s theme would make sense having mechanical rides in it, such as Disney Animal Kingdom’s vintage roadside Americana inspired Dinoland U.S.A.), but it also includes other anachronistic details (contemporary pop music playing in an area that’s supposed to represent the distant past, for example) or structures visible from outside the theme park’s berm (hotels or skyscrapers visible over the horizon in the middle of what’s supposed to be a remote tropical outpost). In many transition zones between themed areas, buildings or props visible from both locations are often designed to be reasonably convincing as part of either series. (The nondescript planks of a wooden shack located between a western frontier area and a jungle adventure area, for example.)

The stratified series is also arranged in space rather than time. Again, while “story” typically implies a dramatic arc and therefore a series of events that change over time, a theme park such as Disneyland often uses series for the opposite effect: to create a permanent, immutable image of an environment frozen in time. The props and buildings in Main Street represent a plurality of unique objects and each have their own distinctive features and quirks, but because they all share a common category, “Small Town Americana,” the themed area can establish a fixed identity. For Hench, the value of a theme park’s organized, stratified series is to create a sense of environmental harmony that contrasts the chaotic feel of the typical cities with many discordant visual elements that create a threatening (although stimulating) impression on its inhabitants.

However, this isn’t to say that environmental storytelling in a theme park is all about using a series of images that identify a fixed, unchanging setting. As the visitor’s eyes scan the surrounding theme park environment they will usually process these objects one-by-one in a sequence, and as they move through the park the series of objects before them will naturally change with location, allowing for a rudimentary form of montage to be established via these spatial relationships. This themed design technique might be called a “relational series,” in which the flow between different elements or areas is strategically controlled. Main Street’s opening sequence is also an excellent example of how juxtapositions to create several key changes and moments of reveal can craft a subtle dramatic arc that primes the visitor’s experience of the rest of the park.

However, this isn’t to say that environmental storytelling in a theme park is all about using a series of images that identify a fixed, unchanging setting. As the visitor’s eyes scan the surrounding theme park environment they will usually process these objects one-by-one in a sequence, and as they move through the park the series of objects before them will naturally change with location, allowing for a rudimentary form of montage to be established via these spatial relationships. This themed design technique might be called a “relational series,” in which the flow between different elements or areas is strategically controlled. Main Street’s opening sequence is also an excellent example of how juxtapositions to create several key changes and moments of reveal can craft a subtle dramatic arc that primes the visitor’s experience of the rest of the park.

As guests approach Main Street, they first pass through a narrow tunnel that constricts their point of view to a collection of attraction posters that build anticipation for the many exciting experiences to come; a series that’s tantamount to movie previews or flipping through a Playbill booklet. They then enter on either side of the town square, “Scene 1,” where they’re suddenly revealed a sprawling series of iconic American imagery that instantly identifies the place and time. As they move down the street, however, there’s a reveal of another large icon that’s specifically intended to break this first established series and create the transition to the next: Sleeping Beauty’s Castle. The juxtaposition of these elements creates intentionally conspicuous contrasts that prompt spectators for interpretation; a castle in the context of a small American street becomes metaphoric in a way that a castle in the middle of a European hamlet might not be. The park’s layout of themed lands can each be thought of as a self-contained series that constitutes a complete scene or act, and the transition areas between lands represent the dramatic equivalent of scene changes, jump cuts, or match cuts.

As guests approach Main Street, they first pass through a narrow tunnel that constricts their point of view to a collection of attraction posters that build anticipation for the many exciting experiences to come; a series that’s tantamount to movie previews or flipping through a Playbill booklet. They then enter on either side of the town square, “Scene 1,” where they’re suddenly revealed a sprawling series of iconic American imagery that instantly identifies the place and time. As they move down the street, however, there’s a reveal of another large icon that’s specifically intended to break this first established series and create the transition to the next: Sleeping Beauty’s Castle. The juxtaposition of these elements creates intentionally conspicuous contrasts that prompt spectators for interpretation; a castle in the context of a small American street becomes metaphoric in a way that a castle in the middle of a European hamlet might not be. The park’s layout of themed lands can each be thought of as a self-contained series that constitutes a complete scene or act, and the transition areas between lands represent the dramatic equivalent of scene changes, jump cuts, or match cuts.

Even the two cannons that sit silently in Town Square are examples of how a spatial series like Main Street can use juxtaposition to add dramatic depth within a purely environmental story. At first these symbols of early industrial warfare likely appear out of place within the rest of the Main Street series, but their contextualized placement against the tranquil surroundings transforms them into an symbol of a “diffused threat” that underscores Disneyland’s central theme of reassurance, and reminds visitors of Walt Disney’s opening dedication of the park to “the hard facts that have created America.” It’s examples like these, among many others, that demonstrate how themed environments use symbols and series in ways to create meaning that, although not technically a “story,” is nevertheless complex and literate.

Even the two cannons that sit silently in Town Square are examples of how a spatial series like Main Street can use juxtaposition to add dramatic depth within a purely environmental story. At first these symbols of early industrial warfare likely appear out of place within the rest of the Main Street series, but their contextualized placement against the tranquil surroundings transforms them into an symbol of a “diffused threat” that underscores Disneyland’s central theme of reassurance, and reminds visitors of Walt Disney’s opening dedication of the park to “the hard facts that have created America.” It’s examples like these, among many others, that demonstrate how themed environments use symbols and series in ways to create meaning that, although not technically a “story,” is nevertheless complex and literate.

Extending the Spectrum: Amusement Parks and More

With theme parks representing one category of location-based entertainment, the question next turns to where and how amusement parks fall in relationship on the spectrum, as well as other types of attractions that may fit between (or beyond) these two formats. Since the focus of this project is primarily on aesthetics, it should avoid hierarchical categorization between theme and amusement parks in favor of a more equal qualitative analysis. There is however, some value in hierarchical classifications from an economic perspective, as the business models that have evolved around these different categories have, in practice, followed a multi-tier niche differentiation pattern, with world-class immersive themed environments coming in near the top of the pyramid in terms of technical complexity and capital expenditure, and small local amusement parks appearing at the bottom.

Amusement parks, like theme parks, rely heavily on symbols and series to communicate their brand and create emotional connections for guests. In many cases they share the same techniques to achieve these ends, such as entrance sequences that convey a special sense of arrival, or “big reveals” of key icons or dramatic vistas. Compare for example the Magic Kingdom’s crossing of the Seven Seas Lagoon and passing beneath the “Here you leave today…” plaque to Cedar Point’s reveal of it’s coaster-dominated skyline across the causeway and passing beneath the gateway arches formed by the GateKeeper roller coaster. Despite the clear differences between the Florida theme park and Ohio amusement park, functionally these title card sequences serve very similar purposes of creating a series of “boundary lines” and iconic imagery that psychologically denote the transition from the ordinary world into the special environment of the theme or amusement park.

Despite the clear differences between the Florida theme park and Ohio amusement park, functionally these title card sequences serve very similar purposes of creating a series of “boundary lines” and iconic imagery that psychologically denote the transition from the ordinary world into the special environment of the theme or amusement park.

However, where amusement parks differ most significantly from theme parks is in the types of symbols they use.  Whereas theme park symbols are almost entirely externalized – the themed objects in Disneyland’s New Orleans Square require the external referent of the real French Quarter New Orleans to make any sense – amusement parks use symbols that are typically organized around their own internal logic. This means that the symbols are typically more abstract in nature (which isn’t to imply an association with the avant-garde, simply that the object doesn’t literally resemble any other concrete object), or if an external symbol is introduced, it’s done more obliquely and to recall an associated mood rather than to directly simulate the referent. An amusement park doesn’t attempt to situate guests in a representation of a far-away or fictional environment, but rather they present a highly stylized, extravagant version of the world as it is before them.

Whereas theme park symbols are almost entirely externalized – the themed objects in Disneyland’s New Orleans Square require the external referent of the real French Quarter New Orleans to make any sense – amusement parks use symbols that are typically organized around their own internal logic. This means that the symbols are typically more abstract in nature (which isn’t to imply an association with the avant-garde, simply that the object doesn’t literally resemble any other concrete object), or if an external symbol is introduced, it’s done more obliquely and to recall an associated mood rather than to directly simulate the referent. An amusement park doesn’t attempt to situate guests in a representation of a far-away or fictional environment, but rather they present a highly stylized, extravagant version of the world as it is before them.

While a roller coaster in a theme park might become fictionalized to simulate the experience of space flight or a runaway mine train, the amusement park presents a roller coaster as an original creation that represents nothing else found in the world except for itself; a sort of postmodern kinetic sculpture towering over the landscape. Thus the concepts of symbols and series as used in an amusement park roller coaster shift to more abstract considerations: the aesthetics of form and movement, choreographing a kinesthetic experience that produces a unique emotional sequence, and creating an attractive kinetic sculpture for onlookers to admire. Where decorative elements are present, they’re typically used to heighten the roller coaster’s intended aesthetic impression, and any signs or symbols typically function through gentle reference rather than aggressive substitution. The most popular of these examples typically involve industrial or horror-inspired design elements to emphasize the adrenaline-induced fear caused by this gravity-driven technology, but the possibilities are endless. A seaside coaster might use a distinctive architectural design and color selection for the loading platform that abstractly connotes the soaring of gulls and rolling of the ocean waves to the movement of the track and trains. Or a steel coaster might stage a series of multicolored loops next to each other as a symbolic tribute to the Olympic games. Likewise, carousels are a prime example of a staple amusement park attraction in which formerly external referents have become internalized. Whereas carousels might have once been seen as a crude form of simulated horse race or jousting tournament, today carousels are more widely regarded as an objet d’art to be appreciated on their own terms; the horses, like sculptures in a museum, are perceived as an expression of artistic craft rather than hyperreal substitutes for the real thing.

connotes the soaring of gulls and rolling of the ocean waves to the movement of the track and trains. Or a steel coaster might stage a series of multicolored loops next to each other as a symbolic tribute to the Olympic games. Likewise, carousels are a prime example of a staple amusement park attraction in which formerly external referents have become internalized. Whereas carousels might have once been seen as a crude form of simulated horse race or jousting tournament, today carousels are more widely regarded as an objet d’art to be appreciated on their own terms; the horses, like sculptures in a museum, are perceived as an expression of artistic craft rather than hyperreal substitutes for the real thing.

Although contemporary amusement parks typically deemphasize some of these aesthetic considerations in favor of maintaining a large collection of mechanical rides (such are the financial realities of the business), there are many notable examples of how good amusement park design is unique from good theme park design, the most notable of which are perhaps the original American amusement parks at Coney Island. The extravagant architecture was world-class relative to the time, and it used symbols and series in a way that made the environment feel distinctly unique from the ordinary outside world, like a toy city for the entertainment of the masses. Although the parks were partly inspired by Greek, Arabian, and Asian architecture (and included some theatrical attractions featuring histories and mythologies associated with those cultures, undeniable precursors to modern themed design), on the whole they were far-removed from the simulated environments that developed in later decades, and were presented as a uniquely American spectacle of technological progress, cultural heritage, and (some might say most importantly) raw hedonism. Flamboyantly self-aware of their theme of American exceptionalism, the Coney Island parks represented only themselves, rather than rely

The extravagant architecture was world-class relative to the time, and it used symbols and series in a way that made the environment feel distinctly unique from the ordinary outside world, like a toy city for the entertainment of the masses. Although the parks were partly inspired by Greek, Arabian, and Asian architecture (and included some theatrical attractions featuring histories and mythologies associated with those cultures, undeniable precursors to modern themed design), on the whole they were far-removed from the simulated environments that developed in later decades, and were presented as a uniquely American spectacle of technological progress, cultural heritage, and (some might say most importantly) raw hedonism. Flamboyantly self-aware of their theme of American exceptionalism, the Coney Island parks represented only themselves, rather than rely on external referents to supply meaning.

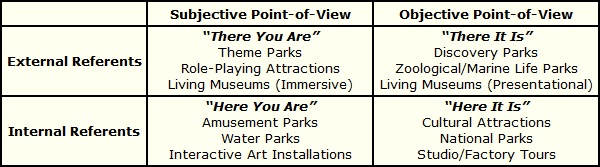

on external referents to supply meaning.