Kings Island – Cincinnati, Ohio

Kings Island – Cincinnati, Ohio

What kind of animal is the Beast supposed to be? It’s been thirty years since its debut, and I don’t believe a clear answer has ever been given to that question. All that’s known is it has two orange-furred, five-clawed paws reaching out from the vanishing point along the track, where the titular lettering rests. What if that lettering was removed and we could see its face? Would we see some sort of feline? Canine? Bear? Chimera?

It’s been thirty years since its debut, and I don’t believe that question has ever been asked because there’s no need to. What waits for us beyond those claws doesn’t need to be filled in by our mind’s eye, everything we need is all there. The Beast is the unknown. It’s the darkness of the night that threatens to engulf us, swallow us whole and spit out our bones. The Beast doesn’t terrify because it’s right in front of you, it terrifies because it’s around the next corner, just out of sight.

doesn’t need to be filled in by our mind’s eye, everything we need is all there. The Beast is the unknown. It’s the darkness of the night that threatens to engulf us, swallow us whole and spit out our bones. The Beast doesn’t terrify because it’s right in front of you, it terrifies because it’s around the next corner, just out of sight.

The Beast has traditionally been regarded as one of the greatest wooden coasters ever built, but within the past decade there has been a backlash from the newer generation of coaster enthusiasts who dismiss the ride because, despite its record length, it doesn’t appear to do much. There’s no airtime hills, no tight transitions or convoluted layout. There are some laterals, most notably at the double helix finale, but even these are sparsely found between looooooooong straightaways that, by all modern criteria, are simply dead space.

looooooooong straightaways that, by all modern criteria, are simply dead space.

To understand the Beast requires that one throw away all expectations and prior knowledge of what makes a good coaster. The Beast isn’t about g-forces, intense pacing or anything of that nature. Other coasters are championed for being radical when they include some extreme variation on those traditions, such as the Voyage with its bounty of extreme banking and drops. The Beast is the only coaster that I would ever call truly radical, because rather than take a pre-established idea to an extreme conclusion, it forces me to rethink the very elemental properties of what makes a good coaster. The Voyage cannot make that claim. That is why the Beast still is the greatest wooden roller coaster ever built.

That is why the Beast still is the greatest wooden roller coaster ever built.

“Sure,” says Timmy the coaster enthusiast, “I could appreciate a long classic ride out in the woods; that might even be top ten for me. But the Beast is not that coaster. There are too many dead sections of track. It may be a good coaster based on the few merits it has, but there could theoretically be a better coaster that featured air hills where there are flat sections, GCI-like twists and turns where there are only level, wide-radius curves.”

“No,” I reply. “That would be a worse coaster”

The Beast is just that radical.

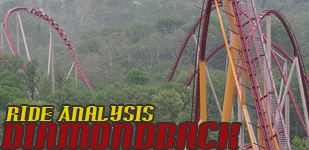

The Beast ride I am going to describe is one that takes place on a busy summer weekend evening; it is both your first ride on the Beast and the last ride of the night, after spending all day riding the fun but uninspired and excruciatingly high-concept Diamondback. The ride begins not at the top of the first lift, not when it first leaves the station, nor when you first board the train, but before you even enter the queue. No coaster hides itself from public

The Beast ride I am going to describe is one that takes place on a busy summer weekend evening; it is both your first ride on the Beast and the last ride of the night, after spending all day riding the fun but uninspired and excruciatingly high-concept Diamondback. The ride begins not at the top of the first lift, not when it first leaves the station, nor when you first board the train, but before you even enter the queue. No coaster hides itself from public view as well as the Beast. Especially as enthusiasts, think about how much information we glean from watching a coaster from off-ride before riding it ourselves. Even if it’s only a first drop or final set of curves that’s visible, it automatically makes the experience that awaits us that much more finite, having been reigned in from the uncharted possibilities by seeing part of it in the flesh (or wood) with our own two eyes. The best the Beast gives us before boarding is the image of the train disappearing from the top of the lift, and everything that happens after it is left to the imagination until actually sitting above those two rails ourselves. In all the years that I’ve known the Beast, I’ve never seen for myself the ‘meat’ of the ride from a spectator’s perspective. Everything I know firsthand about the drops, tunnels and final helix were gathered from only a first-person vantage. Psychologically that’s an extremely different relationship to have with a coaster.

view as well as the Beast. Especially as enthusiasts, think about how much information we glean from watching a coaster from off-ride before riding it ourselves. Even if it’s only a first drop or final set of curves that’s visible, it automatically makes the experience that awaits us that much more finite, having been reigned in from the uncharted possibilities by seeing part of it in the flesh (or wood) with our own two eyes. The best the Beast gives us before boarding is the image of the train disappearing from the top of the lift, and everything that happens after it is left to the imagination until actually sitting above those two rails ourselves. In all the years that I’ve known the Beast, I’ve never seen for myself the ‘meat’ of the ride from a spectator’s perspective. Everything I know firsthand about the drops, tunnels and final helix were gathered from only a first-person vantage. Psychologically that’s an extremely different relationship to have with a coaster.

The information it does give away to potential riders in line is craftily manipulated. When first entering the queue, all that’s visible is the very top of the lift from a distance, as well as a bit of the turnaround out of the station. The queue housing is quite tight and even a bit claustrophobic at times, well protected from the elements but also limiting the field of view. It’s on the ramp upwards to the station that the first up-close glimpse of the Beast happens, watching the departing trains leave the station and slowly make their way around to the lift, which increasingly becomes out of view. The people we see on those trains are a mirror of our present selves: unsure, unknowing individuals and nothing has happened to them yet. It’s not until we are a few trainloads away from our ride that we witness what our future selves might be:

The information it does give away to potential riders in line is craftily manipulated. When first entering the queue, all that’s visible is the very top of the lift from a distance, as well as a bit of the turnaround out of the station. The queue housing is quite tight and even a bit claustrophobic at times, well protected from the elements but also limiting the field of view. It’s on the ramp upwards to the station that the first up-close glimpse of the Beast happens, watching the departing trains leave the station and slowly make their way around to the lift, which increasingly becomes out of view. The people we see on those trains are a mirror of our present selves: unsure, unknowing individuals and nothing has happened to them yet. It’s not until we are a few trainloads away from our ride that we witness what our future selves might be: passengers disembarking from an epic coaster experience that can’t be defined by words but through expressions.

passengers disembarking from an epic coaster experience that can’t be defined by words but through expressions.

Before boarding the train I implore one to take a good look around the station. Thirty years with hardly any updates (the gates are still arranged for a four-bench car configuration the trains had for its first several seasons) and a station that was once designed to approximate a rustic look is now the real deal. So much atmosphere is contained in that house without the need for any props or facades the big-time themers need to give their rides whatever artificial feeling of atmosphere they can. While standing in line for the last ride of the night I passed the time by watching spiders capture and devour insects in a web spun over an old television screen that played static. You simply can’t get that at Disney, I dare them to even try.

Before boarding the train I implore one to take a good look around the station. Thirty years with hardly any updates (the gates are still arranged for a four-bench car configuration the trains had for its first several seasons) and a station that was once designed to approximate a rustic look is now the real deal. So much atmosphere is contained in that house without the need for any props or facades the big-time themers need to give their rides whatever artificial feeling of atmosphere they can. While standing in line for the last ride of the night I passed the time by watching spiders capture and devour insects in a web spun over an old television screen that played static. You simply can’t get that at Disney, I dare them to even try.

Where are we sitting? Front row, all the way. The back is great for rides when you’d like to try it with an extra-aggressive edge to the rattling capable of knocking your filling out (and I mean that in a positive way), and I’ve found the middle a great spot to enjoy a zen-like series of early morning re-rides on the Gold Pass early ride time (on my last visit over Halloween weekend, I got thirteen rides in a row without having to get off the train), but if you’re going to do the Official Beast Night Ride, waiting extra for the front row is the only option available. There’s nothing better than an unobstructed view to highlight the fact that we can’t see anything in the pitch black around us.

There’s nothing better than an unobstructed view to highlight the fact that we can’t see anything in the pitch black around us.

Now we are in the front row, sitting down, waiting to be dispatched for a coaster we still have not seen. The first, slow station turn, past the transfer track, curving along the brake run, engaging the lift hill and then slowly, slowly approaching the top can easily take more than a minute to complete, longer than most modern coasters that hurry to the action as fast as possible for fear that the riders might get bored. Why are we not yet bored of all this… waiting? Because none of this yet, the lift, the station turn, the queue line itself, was waiting in boredom, it was waiting in anticipation, slowly being given bit by bit more information, each piece revealing nothing but acting as a signifier, telling us we are one step closer to this great unknown. And here we are, about to crest the lift hill, and we still haven’t seen any part of the actual ride!

We crest. And there it all is.

That iconic, geometrically balanced image: a long descending straightaway dashed perpendicular to us along the horizon, bridging the double helix on the lower right with the second lift on the upper left. From there the eye notices a ground-level left hand curve that balances the left side of the frame; we trace it until it comes straight down the center, which draws our attention to the most immediate concern, that long straightaway drop into a perilously small tunnel.

that long straightaway drop into a perilously small tunnel.

Many people probably won’t realize this, but we’re now at the exact halfway point of the Beast experience. I’m certain many detractors of the ride saw it their first time through online POV videos and thereby based their initial opinions having unknowingly missed half of the ride. It’s at the crest of the lift where the long buildup in which nothing was known and everything imagined is over. What we have laid out in front of our eyes is the promise of a really rock-and-roll roller coaster… just look at that finale we have coming at the end!

And, for a moment at least, the Beast complies with those expectations. The build-up and anticipation is over, the coaster is here. The first drop is “thrilling” in the most traditional sense of the word. A true wooden roller coaster drop, a massive onslaught of speed and power intended to kick-start the adrenaline from neutral to overdrive in as fast as gravity will allow. Well, most enthusiasts will notice the dynamics of this drop are slightly altered in a way that is to become distinctly Beast-esque; most of the fall is taken over a perfectly straight ramp (it’s officially angled at 45 degrees although I would swear it’s steeper than that), compared to other coasters, particularly modern designs, where the curvature of the lead-in and out factors into much more of the drop. Some first-drop quality air is still present, although that mostly comes from the basics physics equation that tells us anything dropping at an exponential rate of speed will subjectively experience less than one g-force, as there is no curvature that creates outward centrifugal forces as well. I personally would take the Beast’s approach over any other, as the long descent still creates a dramatically fast increase in speed while placing a visual focus on the tunnel and accompanying pull-out that’s about to hit in three…… two… one!

And, for a moment at least, the Beast complies with those expectations. The build-up and anticipation is over, the coaster is here. The first drop is “thrilling” in the most traditional sense of the word. A true wooden roller coaster drop, a massive onslaught of speed and power intended to kick-start the adrenaline from neutral to overdrive in as fast as gravity will allow. Well, most enthusiasts will notice the dynamics of this drop are slightly altered in a way that is to become distinctly Beast-esque; most of the fall is taken over a perfectly straight ramp (it’s officially angled at 45 degrees although I would swear it’s steeper than that), compared to other coasters, particularly modern designs, where the curvature of the lead-in and out factors into much more of the drop. Some first-drop quality air is still present, although that mostly comes from the basics physics equation that tells us anything dropping at an exponential rate of speed will subjectively experience less than one g-force, as there is no curvature that creates outward centrifugal forces as well. I personally would take the Beast’s approach over any other, as the long descent still creates a dramatically fast increase in speed while placing a visual focus on the tunnel and accompanying pull-out that’s about to hit in three…… two… one!

The pull-out hits hard and the tunnel comes fast; it’s incredibly clear at this moment that we are on a wooden coaster, with all the noise and out-of-control intensity that implies. The first drop is much farther than many people probably expect, thanks to the tunnel, which is plenty deep, dark, and over very fast. Yes, that’s what we expect from our coasters, out-of-control intensity that hurries us along from one moment to the next in as quick an order as our synapses will allow. And the Beast continues to comply with those expectations as we blast into a fast, high-intensity left turn without wasting a beat.

Dodging the wooden support structure from the second lift (yet another ‘traditional’ wooden coaster element the ride throws at us in the first ten seconds) riders find themselves poised on the edge of a second drop into a natural ravine. What use of terrain this is! Not only do riders once again find themselves plummeting farther down than the hill up before it was, but the forest here becomes the only thing visible on all sides, a dense canopy sheltering overhead and the ground is invisible from a bottomless sea of evergreen tree-trunks. While perhaps impressive during daylight hours, at night this becomes a haunting awakening to the ride that lay ahead. Suddenly purged from the lights surrounding the first drop and turn, one is unable to tell ground from sky, a hand six inches away from track sixty feet away, for everything their eyes can see has congealed into a single, bible-black canvas. Tunnels only wish they could be this dark.

Dodging the wooden support structure from the second lift (yet another ‘traditional’ wooden coaster element the ride throws at us in the first ten seconds) riders find themselves poised on the edge of a second drop into a natural ravine. What use of terrain this is! Not only do riders once again find themselves plummeting farther down than the hill up before it was, but the forest here becomes the only thing visible on all sides, a dense canopy sheltering overhead and the ground is invisible from a bottomless sea of evergreen tree-trunks. While perhaps impressive during daylight hours, at night this becomes a haunting awakening to the ride that lay ahead. Suddenly purged from the lights surrounding the first drop and turn, one is unable to tell ground from sky, a hand six inches away from track sixty feet away, for everything their eyes can see has congealed into a single, bible-black canvas. Tunnels only wish they could be this dark.

Anyone unable to label those first fifteen seconds as belonging to a great ride ought to be considered criminally insane (or worse, a B&M fanboy). But now begins the controversial part.

(or worse, a B&M fanboy). But now begins the controversial part.

Pulling up from this second drop we slide around a right turn, much more leisurely paced than the first, and we are met with a long covered brake run. Quick! Do what I always do when confronted with a midcourse brake run and try to ignore it as much as possible until we get back into the ride proper! No, the Beast won’t have it. This stretch of track is long, time consuming, and unlike other rides, there’s no going back to the steep drops and sharp turns when it’s over; from here on in, the Beast is doing things its own way.

–

Hold on, time out. So, this is the Beast’s “own way”? Come on! A brake run!?!? How, on any coaster, no matter what kind it is, could a flat brake run be anything less than a dead spot? Maybe on some coasters a brake run at least isn’t a detracting element, but, returning to Timmy the coaster enthusiast’s theory, it should always be fact that a better coaster could exist if it had something more exciting here than a brake run.

And while I hate to spoil things before we get to them, let’s cut the bullshit and fast-forward what’s coming until the second lift hill: wide, flat turn, pause as we enter a tunnel, another flat turn in the tunnel, out of the tunnel a few more straight runs of track with some minor flat turns, no where are any drops more than 15 degrees steep, nor any real g-forces in any direction except a few brief laterals… nothing but running along flat, ground-level track. And then a chain lift.

This is the ride I described as “Greatest Wooden Roller Coaster Ever Built” at the beginning of the analysis. Am I stark raving mad, admitting this all to you? Throughout the history of the Beast there’s been a tradition among enthusiasts where Beast fans try to divert attention away from the indisputable fact that their beloved is mostly flat, forceless sections of track, while emphasizing only the positives:

away from the indisputable fact that their beloved is mostly flat, forceless sections of track, while emphasizing only the positives:

The surroundings are very dark, and it’s evident we’re being taken very far out into No Man’s Land with this stretch of track. Quite a bit of speed is still maintained, and this isn’t Diamondback where you always feel like you’re riding in a luxury sedan no matter what rate of speed you’re traveling at. The Beast trembles, shakes and sometimes heaves in direct correlation to the speed it is traveling as it navigates further downhill and away from civilization. Prowling deeper and deeper through the woods at night in the pitch black on a runaway train ride… that’s why we love the Beast, and there isn’t another coaster on the planet that does what the Beast does any better.

Perhaps that’s all there needs to be. The Beast can be defended as adhering to a doctrine of the minimalist aesthetic principle. Watch the Gus Van Sant movie Gerry while listening to the Philip Glass orchestra, then translate that experience into the coaster realm, and that’s more or less the Beast.

That’s yet to factor the height difference in terrain into the Beast’s equation. While the Beast might have endless stretches of straight track, there is an extremely important distinction that needs to be made: they are endless stretches of straight track angled slightly downhill.

After the long stretch of brake run, the Beast makes a right hand curve that brings us all the way down to ground level to enter a tunnel, and as such our instincts might be that this is as fast as this second part of the ride will get. The tunnel becomes its own highlight just by virtue of how long it holds us in an all-encompassing blackness, at least during night rides. This tunnel is actually two short underground segments at either end bridged by a longer aboveground segment that’s mostly enclosed. During the day a lot of light is leaked through; on my last visit I don’t believe there was any paneling along the bottom of the track, and the wooden planks that form the sides had small gaps between them, creating the appearance of a solid tunnel when looking forward but when viewed at from the side a zoetrope effect was created

After the long stretch of brake run, the Beast makes a right hand curve that brings us all the way down to ground level to enter a tunnel, and as such our instincts might be that this is as fast as this second part of the ride will get. The tunnel becomes its own highlight just by virtue of how long it holds us in an all-encompassing blackness, at least during night rides. This tunnel is actually two short underground segments at either end bridged by a longer aboveground segment that’s mostly enclosed. During the day a lot of light is leaked through; on my last visit I don’t believe there was any paneling along the bottom of the track, and the wooden planks that form the sides had small gaps between them, creating the appearance of a solid tunnel when looking forward but when viewed at from the side a zoetrope effect was created with the passing woodland scenery on the outside.

with the passing woodland scenery on the outside.

The track inside the tunnel is another one of those moments where nothing really happens besides a long, wide turn to the right; by all accounts it’s essentially just as much ‘dead track’ as the shed-covered brake run that preceded it, it’s just that this stretch one-ups it a little bit by being completely enclosed, and by taking place along a curve it not only throws some minor laterals into the mix but it hides what’s coming ahead. The shed run, by opposites, was all about anticipating what’s coming after it, the end remaining in sight along the entire stretch and yet elusively out of reach because the track is just so long. That is actually a recurring theme found throughout the Beast, an awareness of space and motion achieved by approaching vanishing points (another reason why sitting in the front row is a must).

However, nearing the end of the tunnel, one might detect a sensation that we are now gaining speed. The last straightaway leading us back into the exposed outdoors is in fact pulling us downhill at a surprisingly strong pace, surprising because we don’t recall ever starting to slope this steeply downhill, and it’s impossible to sense from the surrounding terrain that we even have moved downhill at all from when we first entered the tunnel; this gaining speed since the shed run seems to be ex nihilo, created from nothing.

What amazes me about this stretch of the Beast is not just that it’s capable of mysteriously building speed (the track remains consistently five feet above the ground at all times after exiting the tunnel), but somehow that it’s able to exponentially increase the rate of gained speed. Presumably this is because the land we’re traveling over somehow becomes steeper, but a glance around at our surroundings gives the illusion we’ve not experienced more than a twenty-foot change in elevation since the beginning of the ride; the land at least appears mostly all flat, without the ravines or valleys we might normally associate with so much speed gain.

Pouring hard into the next right hand turn out of the tunnel, this one builds upon the last turn further by providing even more laterals and increased speed. That’s not to say that this coaster is ‘about’ laterals in the same way a ride like the Legend might be described. In an absolute sense the lateral forces here are still somewhat light, but relatively speaking every second is “building” on the one before it, even though it’s not “in intensity”. The speed is ever increasing, and perhaps most notably it’s the increased shaking and rattling of the cars that best signifies increased danger. It all adds together to create the indelible impression that we are climaxing towards something, but what, it’s hard to say…

Pouring hard into the next right hand turn out of the tunnel, this one builds upon the last turn further by providing even more laterals and increased speed. That’s not to say that this coaster is ‘about’ laterals in the same way a ride like the Legend might be described. In an absolute sense the lateral forces here are still somewhat light, but relatively speaking every second is “building” on the one before it, even though it’s not “in intensity”. The speed is ever increasing, and perhaps most notably it’s the increased shaking and rattling of the cars that best signifies increased danger. It all adds together to create the indelible impression that we are climaxing towards something, but what, it’s hard to say…

A slight pattern emerges in this last dash of the ride as a straight, ground level stretch of track builds in speed as it anticipates a curve to the right, which is repeated a total of three times after exiting the tunnel. After the second turn, which has a slight crest over a natural hill, the track follows a downward contour in the land and the speed really explodes in these final moments as we charge into the final right turn. Laterals are probably at their most intense on this final maneuver but it’s a quick turn that’s over before even realizing it. It’s much more about the lead into this curve, a long prebank that feeds directly into the turn with no transition from straight to curve, so the laterals hit hard all at once before they just as quickly dissipate.

The official speed of the Beast is listed as 64.77 mph, (an absurdly precise measurement especially for a wooden coaster) but there’s a bit of confusion over exactly where that happens. One normally assumes this refers to the first drop, but the park clarifies this speed as occurring on the ‘third hill’, a bit of an ambiguity since there are no real drops after the second one into the ravine, possibly referring to the second lift drop into the helix. However, rumor has it that back in the day it was actually at this moment where the Beast achieved maximum velocity, an astounding feat considering there haven’t been any authentic drops after finishing with the shed run; that speed was created via nothing but a long and arduous buildup that takes nearly a minute to reach its full potential, and once it’s been reached, the coaster does nothing with it but quickly let up and start the climb back uphill and into the second lift. It even goes so far as to tease us, once the speed has mostly been lost, with another slight downward slope that feels like we start to get some of the power back before the pace once again quits for good with the lift.

this speed as occurring on the ‘third hill’, a bit of an ambiguity since there are no real drops after the second one into the ravine, possibly referring to the second lift drop into the helix. However, rumor has it that back in the day it was actually at this moment where the Beast achieved maximum velocity, an astounding feat considering there haven’t been any authentic drops after finishing with the shed run; that speed was created via nothing but a long and arduous buildup that takes nearly a minute to reach its full potential, and once it’s been reached, the coaster does nothing with it but quickly let up and start the climb back uphill and into the second lift. It even goes so far as to tease us, once the speed has mostly been lost, with another slight downward slope that feels like we start to get some of the power back before the pace once again quits for good with the lift.

A minute of buildup with no payoff at the end? That’s looking at it the wrong way. In dramatic structures, the more powerful tension comes from a build-up that doesn’t allow a release from its hook after it’s done, rather than one that ends with the expected payoff and catharsis which trivializes the suspense that preceded it. As we climb the second lift hill, instead of cheering and wiping our brow relieved, we’re still engaged with the ride even though at the moment it appears to have stopped; it still haunts us. And for those that know what’s waiting for us on the other end of the lift (everyone had a good glimpse of it at the top of the first lift) knows that the Beast isn’t finished yet.

Reaching the top of the second lift, we are momentarily disengaged from all that accumulated, unresolved tension as for the first time since we left the station we feel a sense familiarity of our surroundings. There’s Vortex, the Eiffel Tower, Racer and Son of Beast off in the distance, and as we start to turn left we even spy Diamondback sticking up over the hills, pathetically scratching into the deeper reaches of the woods we’ve just been through. This turn isn’t exactly the archetype of quality engineering; the cars creak oddly as they try to tilt into the bank, and the inconsistent radius gives the appearance that we’re straightening out before it smashes us hard to the right as it attempts to align with the long down ramp. And straight ahead is a sight even more memorable than the one seen at the top of the lift.

Reaching the top of the second lift, we are momentarily disengaged from all that accumulated, unresolved tension as for the first time since we left the station we feel a sense familiarity of our surroundings. There’s Vortex, the Eiffel Tower, Racer and Son of Beast off in the distance, and as we start to turn left we even spy Diamondback sticking up over the hills, pathetically scratching into the deeper reaches of the woods we’ve just been through. This turn isn’t exactly the archetype of quality engineering; the cars creak oddly as they try to tilt into the bank, and the inconsistent radius gives the appearance that we’re straightening out before it smashes us hard to the right as it attempts to align with the long down ramp. And straight ahead is a sight even more memorable than the one seen at the top of the lift. Two rails skewing around to the right as they coalesce into a black hole.

Two rails skewing around to the right as they coalesce into a black hole.

The next six seconds as we angle down this 141 ft. drop angled at only 17 degrees are a potent repackaging of everything from the last two minutes: straight track with long banking leadins, accumulating speed, vanishing points, and ratcheting psychological tension without any physical aggression. By emulating these same techniques the mind is able to better contextualize this moment than if it had been randomly inserted in the middle of a traditional coaster experience. The repetition in familiar elements creates the subconscious sensation that this too will end without payoff, sharply conflicting with new sensations and setting that indicate we’re anticipating something new and altogether terrifying.

This is an incredible finale. There are no g-forces on this lead-in, besides the pull from the increased banking, yet you would have to have ice for blood to feel nothing. The increasing wind, the train shaking and heaving more and more, the track tipping us over farther and farther as we anxiously wait for that still intangible helix to inevitably hit (the track seems to just end at the mouth of the tunnel, so we can’t actually see what it is we are bracing for).

Closer and closer, faster and faster, steeper and steeper… ______ but still not there…

It hits. Pummeling us against the other side of the train. The world goes black. Screams from the riders are inaudible over the screaming of steel wheels. The train tries to break free from the track. Laterals so strong they make the Legend look weak. Rarely does a coaster ever scare me these days, but this helix easily would make my list of the five or so coaster moments that still do, even after having ridden them many times.

We burst out of the tunnel, and there’s a sudden calm as the train navigates the next 180 degrees. It can be hard to tell but this helix contours against a steep hillside, and the lower, covered portion of the helix is probably a good 50 ft. below this upper portion. Call this the eye of the hurricane before the train enters the upper level of the tunnel. Again, the train shakes, howls and mercilessly throws us against the right side of our seats, this sensory overload for our ears and nerves while devoid of visual stimulus is perfectly contrasted by the serene, open air middle portion of the helix. After a half hour of anticipation, we have finally gotten to the payoff. And it was well worth it.

As soon as we exit the upper level of the tunnel, there is once again quiet, the intense laterals seeming to let up the moment we can see light (or at least, moonlight). I always hate a ride that, after the big finale, tries to entertain us a bit more with lesser filler material before reaching the brake run. While we still have to get around the final leg of the turn and up into the brake run, it’s so gentle that compared to the helix my brain hardly ever registers it, and the ride is as good as over at this moment. We return to the station, secretly wishing we could turn back the clock and rejoin those unknowing faces still waiting for their turn in the station. Every time I feel that envy I know I’ve just been on a truly great roller coaster.

As soon as we exit the upper level of the tunnel, there is once again quiet, the intense laterals seeming to let up the moment we can see light (or at least, moonlight). I always hate a ride that, after the big finale, tries to entertain us a bit more with lesser filler material before reaching the brake run. While we still have to get around the final leg of the turn and up into the brake run, it’s so gentle that compared to the helix my brain hardly ever registers it, and the ride is as good as over at this moment. We return to the station, secretly wishing we could turn back the clock and rejoin those unknowing faces still waiting for their turn in the station. Every time I feel that envy I know I’ve just been on a truly great roller coaster.

Still, I feel as though I’ve failed to justify my original claim that the Beast is the Greatest Wooden Coaster Ever Built. Holiday World’s Voyage can easily be described as at least most of those things, and there’s a lot more happening with that ride as well. Okay, even the Voyage doesn’t have quite as strong a factor of venturing into the unknown that the Beast has when climbing aboard, but things like the record amount of airtime, underground triple down and ninety degree banking should more than make up for all that and put it at least on par if not well above the Beast. And if not the Voyage, there are other coasters that are equally strong contenders, such as El Toro’s extreme airtime, power and precision, Thunderhead’s intricate turns and lightning fast pacing, or the Phoenix’s classical and abundant airtime appeal. Each more than succeeds at doing what it’s intended to do, so why am I giving special treatment to the Beast just because it also seems to succeed at what it does?

Still, I feel as though I’ve failed to justify my original claim that the Beast is the Greatest Wooden Coaster Ever Built. Holiday World’s Voyage can easily be described as at least most of those things, and there’s a lot more happening with that ride as well. Okay, even the Voyage doesn’t have quite as strong a factor of venturing into the unknown that the Beast has when climbing aboard, but things like the record amount of airtime, underground triple down and ninety degree banking should more than make up for all that and put it at least on par if not well above the Beast. And if not the Voyage, there are other coasters that are equally strong contenders, such as El Toro’s extreme airtime, power and precision, Thunderhead’s intricate turns and lightning fast pacing, or the Phoenix’s classical and abundant airtime appeal. Each more than succeeds at doing what it’s intended to do, so why am I giving special treatment to the Beast just because it also seems to succeed at what it does?

Frankly, I grappled with that problem a long time. After my first rain-slicked night ride on the Voyage in 2006 when it was running with lightning pacing, by all my own declared standards of what makes a #1 coaster I should have then and there dumped the Beast from my top position and replaced it with that ride. But I couldn’t. Was it just that I had become too sentimentally attached to my long-time favorite roller coaster? Secretly I thought I might have been, but I held belief that there was something besides sentiments that made the Beast the better ride. And slowly, I think I uncovered what it is.

Every other coaster ever built since La Marcus Adna Thompson first envisioned a gravity thrill device for the shores of Coney Island all work in a near identical psychological fashion. They’re experiences created by individual moments. A sentient being existing at a specific point in space-time, contorted in whatever way possible best maximizes that beings’ immediate enjoyment via instantaneous neural feedback created by unusual physical and sensual scenarios. A hill followed by a turn followed by a loop and so on. Sometimes that’s best achieved by allowing a second of pause to set up and highlight next big moment, but the ride is always fundamentally about these moments.

The Beast isn’t. After teasing the rider with a glimpse of a traditional roller coaster experience in the first few seconds off the chain lift, it abruptly and willfully abandons those traits for an experience that has no specific moments for our minds to latch onto. We are taken out of the moment and instead are looking forward into the building kinetic energy that waits ahead. The shed-covered brake run becomes a highlight of the ride only after the moment has passed, somewhere down along the high speed ground section before the second lift, where without the contrast of a seemingly anticlimactic moment earlier in the experience would render that later section of the ride trivial. The mind expands and begins to think of the coaster as something that doesn’t happen in the here-and-now but across space-time. To do something like build an airtime hill in the middle of this coaster would completely destroy the creation of tension and anticipation and put us back into riding for individual experiential moments.

In addition, the sheer length of the Beast creates a different psychological state than you would get at the end of a ride half its size. Unlike many coasters we might finish the ride with the beginning of it still in our short-term memory. With the Beast, by the time we get to the conclusion, as we reflect back on how this whole epic experience started we are instead reaching into our long-term memory and the result is surprisingly different. While on any coaster under two minutes I still feel temporally connected to the outside world, while on the Beast my entire sense of existence starts to become defined by the ride and I become lost in the experience (not entirely dissimilar to the experience of watching an epic movie and eventually forgetting about the reality outside the film because my entire sense of being has been completely absorbed by it).

This all might delve into a deeper, philosophical of the role of the human mind. As someone is consciously riding a roller coaster, is the mind only engaged in the experience to the extent that it is used as a receptacle for sensory data? Many people seem to be content with that function, and if so I hope that attitude doesn’t carry on to the rest of their life because to claim that human consciousness is limited only to sensation seems to be rob us of a vital element of our humanity. It implies that right now all your mind is doing is sensing an arrangement of black and off-white pixels, and that later you will become fearful of death not out of any existential understanding of what death is but solely because your genetic code is programmed to release chemicals that create negative sensations deter you from the thought. It is not enough, at least not for me, to simply extrinsically sense lateral g-forces or airtime or what have you. It is necessary to also intrinsically comprehend these sensations and understand what they mean within the context of my own being.

With so many long, flat sections of track, it’s clear that the secret of the Beast has hardly anything to do with just perceptual sensations. It plays with human emotions in a way no other coaster does. When we round that first right-hand turn after the ‘exciting’ ravine drop and encounter the long strip of deceleration, even I still feel a sense of disappointment and sadness at first. These are real emotions I am experiencing, just as valid to the ride experience as a sense of thrill or enjoyment that we normally expect from a coaster and use to benchmark how good or bad a ride is. (I’ve often wondered if it’s possible to design a ride that evokes other emotions, in that someone’s response wouldn’t just be scream or cheer, but to laugh, cry, feel pensive or envious or regretful or nostalgic.) Later, when the Beast is once again hauling down the hillside at full speed, by cognitively reflecting on that original emotional state of disappointment it is then transformed into new emotions of at first relief and then anxiety and excitement; none of these feelings are caused by the sensory feedback of the immediate riding environment. The result is that if you’re not in at least some degree psychologically ‘in-tuned’ with what the Beast is trying to do, then you will still be able to feel nothing from the ride. However for people that can understand what I’m (perhaps poorly) trying to communicate here, then perhaps you can see what I meant when I first called the Beast radical in ways that no other coaster is.

Alas, I must confess that everything written above might be for naught (assuming it made any impact to begin with; I fear I might have been swimming in waters above my head with the previous few paragraphs, but I suppose it’s better to try and fail than to not try at all). If you were to drive out to Kings Island today you would not be able to ride exactly the coaster I described above. In the park’s numerous attempts to ‘modernize’ the Beast over the past several years (most notably with the replacement of the original skid brakes with magnetic brakes in 2002) they have perhaps unknowingly taken a lot away from the ride. These magnetic brakes now severely hold the train on the first drop, second drop into the ravine, along the old skid brake run and along the downward ramp into the helix, each dramatically impeding that sense of slowly building climax I emphasized so strongly in my defense of the coaster. Admittedly all of those locations with the exception of the ravine drop had skid brakes along them before, but those were barely effective and even if they did rob the train of some forward momentum the deceleration was spread over a much longer stretch of track so it wasn’t a noticeable force thrusting us forward into the restraints. On the first ride of the morning on a cold October morning when I was the only passenger in the train, we probably came within walking speed at the exit of the shed run brake (that it still powered through the last few curves on that stretch of track is a testament to how much terrain difference is utilized in that middle section).

The coaches we ride in aren’t the ideal they used to be, although given what some parks do to their wooden coaster trains it could be a lot worse. Actually the retracting seatbelt feature is nice, it helps with load times and makes sure everyone’s in securely without ever being tight or restrictive. However the seat dividers come up all the way along the seat back and can jab at the ribs if you’re not careful. Again, this is all a bit nitpicky and there have certainly been far more horrendous examples of wood coaster rolling stock, but it’s still a far cry from the days it had single-position lapbars, no headrests and no seat dividers, which I sadly never got to experience it with. I remember on my first ride ever on the Beast in 1996 my lapbar ratcheted down really tight on the first drop and I spent the rest of the ride watching my legs turn blue. I hated the Beast until I visited it again in 2001 (the year before the magnetic brakes) and that last ride of the night made a very permanent impression on me, to say the least.

it helps with load times and makes sure everyone’s in securely without ever being tight or restrictive. However the seat dividers come up all the way along the seat back and can jab at the ribs if you’re not careful. Again, this is all a bit nitpicky and there have certainly been far more horrendous examples of wood coaster rolling stock, but it’s still a far cry from the days it had single-position lapbars, no headrests and no seat dividers, which I sadly never got to experience it with. I remember on my first ride ever on the Beast in 1996 my lapbar ratcheted down really tight on the first drop and I spent the rest of the ride watching my legs turn blue. I hated the Beast until I visited it again in 2001 (the year before the magnetic brakes) and that last ride of the night made a very permanent impression on me, to say the least.

What’s interesting to note is that none of these complaints come from the fact that the ride isn’t being well-maintained by the park as is normally the case with older wooden coasters like this, but rather from the park taking too proactive a stance in preserving the ride for loving guests. Their latest endeavor is perhaps the most sadly ironic of them all… the complete retracking of the helix finale. Normally that’s a very good thing, but not only was it retracked, many of the ledgers and supports have also been replaced; fairly extravagant treatment for a wooden coaster that’s 30 years old, especially one owned by a corporate park. So why did that have to include considerably increasing the banking pitch of the helix? On my first ride of the season last May, this is how the narrative actually went:

What’s interesting to note is that none of these complaints come from the fact that the ride isn’t being well-maintained by the park as is normally the case with older wooden coasters like this, but rather from the park taking too proactive a stance in preserving the ride for loving guests. Their latest endeavor is perhaps the most sadly ironic of them all… the complete retracking of the helix finale. Normally that’s a very good thing, but not only was it retracked, many of the ledgers and supports have also been replaced; fairly extravagant treatment for a wooden coaster that’s 30 years old, especially one owned by a corporate park. So why did that have to include considerably increasing the banking pitch of the helix? On my first ride of the season last May, this is how the narrative actually went:

Closer and closer, faster and faster, steeper and steeper… but still not there…

It hits. Wait, did it really? Just now? I don’t feel much of anything except for some mildly strong positives and with such light, controlled laterals that any CCI would laugh at it. When we got back to the station I asked one of the attendants if they really had increased the banking over the off-season his reply was, “yeah, they sure did! Isn’t it so much smoother now?”

they sure did! Isn’t it so much smoother now?”

I might be slightly understating things when I say that transforming the finale that the entire five minutes of ride time before it had been slowly climaxing toward from the original batshit insane maelstrom into a completely neutered, basic curving maneuver completely and utterly fucks the ride several times over. Listen, Kings Island, I appreciate the thoughtfulness but am I honestly in the minority that thinks the way to a better Beast is by a smoother, more controlled ride? I thought the general consensus was that the feeling of being out of control was what people loved about the ride, so why would you deliberately try to neutralize that experience? As I watch the crowds eat up Diamondback I guess tastes must be changing. Thankfully part of the problem with that first ride this season might have been it just hadn’t fully broken in yet, since it was somewhat more like its old self in August, and over the Halloween weekend, while it wasn’t running as fast as it had been on a hot summer night there was still at least a bit of an edge left over.

One last gripe that’s always been a part of the Beast is that I wish they didn’t have to run that maintenance road along the entire section of track after the second tunnel and before the lift. This is the section of the ride that the woods should make the most powerful presence as we are at the most remote reaches from the park, but instead we feel like we’re somehow out in the clear and not far from home, plus the sense of speed is diminished with the reference points pushed further away from us. I also noticed this year that one or two of the hills on Diamondback are now visible from this back section since we don’t have much tree cover, which might not seem like that big of a deal (I remember when it was first announced I worried they’d try building over the same land as the Beast) but it gives away our location in regards to the rest of the park with the sight of something familiar; when you exit that second tunnel you could almost believe you’re in the next state, so removed from anything resembling an amusement park you are. Thankfully like a few other of the Beast’s drawbacks, this problem is alleviated at night.

For anyone out there that is planning a first-time visit to Kings Island, I would recommend including an evening ticket before a full day in the plans, since not only is there probably that much to do in the park but it’ll let one experience the Beast for the first time after night fall, which is how everyone should experience it for the first time in their lives, even if it doesn’t win you over and also ends up being your only time.

Despite my numerous complaints about the performance of the coaster in recent years, the core of the ride experience is still all there (although the helix modifications came really close to fundamentally altering that essential core). And although Diamondback may have been garnering the most buzz for the park over this past season, at the end of the night it was still the Beast that played host to the most enthusiastic crowds, the entire trainload erupting into a symphony of cheers when they got back to the station. So congratulations, Beast, you’ve officially completed thirty-one seasons. Here’s to hoping your best years are still ahead of you.

(P.S. This POV video below I think well captures the Beast ride I was trying to describe in this analysis. Including the full preride section and the older pacing before the magnetic brakes, it’s even filmed on a very overcast day, emulating to some degree the night ride environment.)

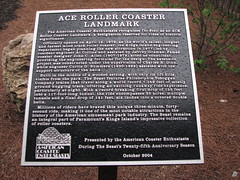

Photos credited to: CoasterImage.com (all backstage offride); Wayne Stueber (Aerial); Kings Island (First drop). Used with permission.

(On-ride photos were provided by a source who wished to remain anonymous to me. Please do not attempt to take on-ride photos of rides yourself without the parks permission.)

Comments