Cleebronn, Germany – Saturday, March 27th, 2010

How meta can this place get? Erlebnispark Tripsdrill is Germany’s oldest operating amusement park, opening in 1929 with a windmill slide built as a side attraction for the restaurant. Over the years as it became more popular, it grew into a symbol for the Germanic culture with museums featuring the local history, buildings constructed using the local architectural styles, and an all-around atmosphere that couldn’t be found anywhere else but in Germany. It’s for attractions like these that we travel, right? But as the zeitgeist marched towards modernity, Tripsdrill became a theme park, and a first-rate one at that. Rides with impressively-detailed settings and elaborate enclosed queues with audio-animatronic characters and multi-media displays meant to create a fully-immersive environment… all themed to what? The very same Germanic culture that this attraction was once a symbol for! Erlebnispark Tripsdrill is a traditional German park themed to traditional German parks!

As I first walked into the gates on their drizzly, overcast opening day of the 2010 season, it struck me as a rather peculiar choice of representation that there should have to be façades themed to be hyper-real versions of the buildings within the same town, animatronic characters representing the very people whom presumably still live not a few kilometers away, and landscaping meant to simulate the German countryside that surrounds it but on a smaller scale. After all, isn’t the main selling point of a theme park to escape from reality into someplace different? For locals this really isn’t an escape and for tourists that have bother to come all the way to Germany, why settle for a replica they could theoretically get anywhere in the world when the real thing lay just beyond the admission gates? There’s probably another one of my

As I first walked into the gates on their drizzly, overcast opening day of the 2010 season, it struck me as a rather peculiar choice of representation that there should have to be façades themed to be hyper-real versions of the buildings within the same town, animatronic characters representing the very people whom presumably still live not a few kilometers away, and landscaping meant to simulate the German countryside that surrounds it but on a smaller scale. After all, isn’t the main selling point of a theme park to escape from reality into someplace different? For locals this really isn’t an escape and for tourists that have bother to come all the way to Germany, why settle for a replica they could theoretically get anywhere in the world when the real thing lay just beyond the admission gates? There’s probably another one of my famous analyses/rants boiling beneath the surface of that thought. I’ll let it simmer for a bit as I do a review of the park and all of the rides, and then pick it back up at the end, okay?

famous analyses/rants boiling beneath the surface of that thought. I’ll let it simmer for a bit as I do a review of the park and all of the rides, and then pick it back up at the end, okay?

The infrastructure layout of Tripsdrill is possibly the strangest I have ever encountered at a park. To get to the corner on which Mammut is located (think of the park as a large square, the entrance and Mammut are at opposite corners) you first have to cross to the back of the park, and then turn around and cross back to the front. You then have to walk along the front edge until finding the open clearing along which the Flume and G’sengte Sau are located, where you may then walk directly back to Mammut. Essentially it’s the same distance as if you were to walk the entire  perimeter of the park once. Incredibly confusing without a map, but once I adjusted it was not without its charms.

perimeter of the park once. Incredibly confusing without a map, but once I adjusted it was not without its charms.

For one, it’s a very beautiful park, especially in the original section near the entrance. Lots of timber-framed buildings, gardens, trees, and other miscellaneous objects scattered about as if a small German hamlet, oddly complete with clotheslines hanging out to dry over the pathways. At the end of the main midway is the park’s first ride, the Maypole, a small, rotating parachute/observation tower of sorts. It doesn’t quite go high enough to get a view of the entire park, but still remains a pleasant diversion and is a good way to begin a visit to the park regardless.

On the left was a woodsy section with a few rides located around a small pond, a petting zoo I believe just beyond it. A few attractions of note include a walkthrough fun house with several sections of downhill catwalks made of rollers that would sure to be banned in the US. Even better however is the Doppelter Donnerbalken, which at first glance appears to be a slightly larger and more expensive version of an S&S Frog Hopper, which in a way it is. Extra height and two-row deep floorless cars are a plus, as is an elaborate treehouse theme disguising the tower (actually towers, as there are two facing each other) which shows no expense was spared. But best of all, is after a bouncy cycle to the top, the entire car suddenly tips forward by several degrees before plunging in freefall all the way to the bottom. As there was no

On the left was a woodsy section with a few rides located around a small pond, a petting zoo I believe just beyond it. A few attractions of note include a walkthrough fun house with several sections of downhill catwalks made of rollers that would sure to be banned in the US. Even better however is the Doppelter Donnerbalken, which at first glance appears to be a slightly larger and more expensive version of an S&S Frog Hopper, which in a way it is. Extra height and two-row deep floorless cars are a plus, as is an elaborate treehouse theme disguising the tower (actually towers, as there are two facing each other) which shows no expense was spared. But best of all, is after a bouncy cycle to the top, the entire car suddenly tips forward by several degrees before plunging in freefall all the way to the bottom. As there was no queue I didn’t get to see a cycle run before I tried it for myself so the effect took me completely by surprise. Honestly a bigger thrill than Tower of Terror five days ago. Definitely a must-ride for anyone visiting the park (hopefully I didn’t spoil the surprise for you).

queue I didn’t get to see a cycle run before I tried it for myself so the effect took me completely by surprise. Honestly a bigger thrill than Tower of Terror five days ago. Definitely a must-ride for anyone visiting the park (hopefully I didn’t spoil the surprise for you).

Around the side of the pond meeting up with the ‘main midway’ (as central a midway as can be found at Tripsdrill, at least) is the Altweibermühle, aka the Old Windmill, and the park’s oldest ride. Inside you can climb to the top, and then take the most awesome burlap sack slide I’ve ever been on back to the bottom. I did this thing at least five times over the course of the day, despite having walked the distance uphill myself, the drop down always goes much further and faster than expected. Another must-visit for the park.

Beneath their large restaurant was a room labeled the Trillarium which I went to investigate what it contained. It turned out to first house a large machine gun collection, followed by a second room filled with various life-size figurines of German people. Odd to say the least. Around the side of the building was another stable with yet more animatronic people on display, a rather creepy sight whose purpose wasn’t entirely clear.

Of more clear purpose were some of the rides in the area, which included a lengthy powered car ride (Weinkübelfahrt), with the cars shaped as spinning barrels which navigated an elaborate course around trees and gardens I’m sure would look stunning if not for it being the first day of the season and they had yet to be in bloom. I passed on a ride on this particular attraction which I shouldn’t have, but such is life. Further back appeared to be another children’s section which I didn’t explore (partly for fear of becoming completely lost even with my park map).

Interactive fountains, dioramas, and other features litter the network of winding narrow pathways almost to the point that the entire park feels like one big walk-through attraction. A few of the mechanical rides present in the area include the Gugelhupf-Gaudi-Tour (a tilt-a-whirl ride themed to a bakery) the iconic Wirbelpilz (Mushroom Swing) and Schlappen-Tour (a sort of Jr. Himalaya themed to shoes). Of most especial note to the coaster enthusiasts is the first roller coaster to find in the park, the Rasender Tausendfüßler.

Interactive fountains, dioramas, and other features litter the network of winding narrow pathways almost to the point that the entire park feels like one big walk-through attraction. A few of the mechanical rides present in the area include the Gugelhupf-Gaudi-Tour (a tilt-a-whirl ride themed to a bakery) the iconic Wirbelpilz (Mushroom Swing) and Schlappen-Tour (a sort of Jr. Himalaya themed to shoes). Of most especial note to the coaster enthusiasts is the first roller coaster to find in the park, the Rasender Tausendfüßler.

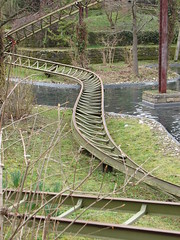

This was having some lift hill problems when I first arrived, but they fixed it after applying the practical diagnostics method of testing it ten times in a row until it spontaneously works one of those times. Technically there’s nothing special about this ride as it’s a basic Large Tivoli layout which can be found at parks all across the world, but what makes this one special is the fantastic landscaping surrounding it making it almost as fun to watch as it is to ride. Riding is great fun too, however, mostly because of how close to the ground it gets. Anyone that wants to can easily reach out and run their fingers through the grass on the

one of those times. Technically there’s nothing special about this ride as it’s a basic Large Tivoli layout which can be found at parks all across the world, but what makes this one special is the fantastic landscaping surrounding it making it almost as fun to watch as it is to ride. Riding is great fun too, however, mostly because of how close to the ground it gets. Anyone that wants to can easily reach out and run their fingers through the grass on the ground-level banked turns, of which the bottom part of the I-beam rails essentially sit flat on the soil. Never before has a 15mph roller coaster feel maybe a little bit too fast.

ground-level banked turns, of which the bottom part of the I-beam rails essentially sit flat on the soil. Never before has a 15mph roller coaster feel maybe a little bit too fast.

As I had not had anything to eat since the vending machine snacks at the Vienna train station the previous night, I needed to grab a lunch. A walk-up tray service location with a long menu seemed the more promising in the park outside of the sit-down restaurant, but unfortunately the menu was entirely German cuisine and they offered no translations. Looking over it I could easily figure the “mit Pommes” phrase attached to every entrée meant “with Fries”, but for the main course itself I was clueless if I might inadvertently be ordering roasted hog’s snout… save for one item I recognized: Bratwurst (mit Pommes). Since today was my first day in Germany I felt I should be a bit more adventurous than that, so I decided to ask at the counter if anyone speaks English, and if so if they can make a menu  recommendation for a first time German traveler.

recommendation for a first time German traveler.

The first lady I spoke to knew almost no English, but they rounded up the one cook who supposedly did speak my mother tongue. I re-asked my question “what is recommended?” (which is a lousy question since it seems all hospitality businesses are required to helpfully unhelpfully answer “whatever you’d like the most”) but my supposed translator looked at me as if I were chanting voodoo incantations, so I gave up and settled on the bratwurst, which wasn’t particularly special, at least for the price.

Rounding out the set of attractions in the original part of the park is Waschzuber-Rafting, which I believe was their  first truly large scale ride investment sometime back in the mid-1980’s. Perhaps against my better judgment given the cold, wet climate I decided to take a ride, not knowing how wet I might get but operating under the impression that “European water rides aren’t that wet”. While I would definitely discover that statement to be false, it would not occur to me today, as I made it through with only the lightest of sprinkles tosses up on some of the rapids. That’s not to say I didn’t nearly shit myself when I saw the channel approaching a large waterfall… which turned off a moment before the raft passed under. Thank god those sensors were working properly the first day of the season. While nicely landscaped and themed (apparently to clothes washing, as there were detailed sets built along the queue illustrating), there wasn’t anything

first truly large scale ride investment sometime back in the mid-1980’s. Perhaps against my better judgment given the cold, wet climate I decided to take a ride, not knowing how wet I might get but operating under the impression that “European water rides aren’t that wet”. While I would definitely discover that statement to be false, it would not occur to me today, as I made it through with only the lightest of sprinkles tosses up on some of the rapids. That’s not to say I didn’t nearly shit myself when I saw the channel approaching a large waterfall… which turned off a moment before the raft passed under. Thank god those sensors were working properly the first day of the season. While nicely landscaped and themed (apparently to clothes washing, as there were detailed sets built along the queue illustrating), there wasn’t anything of particular excitement along the course of the rapids save for the waterfall effect. That’s not counting the whirlpool element near the end, which from offride looks like a pretty fascinating element, but from onride it’s just a flat, curving channel around the outside of a whirlpool effect.

of particular excitement along the course of the rapids save for the waterfall effect. That’s not counting the whirlpool element near the end, which from offride looks like a pretty fascinating element, but from onride it’s just a flat, curving channel around the outside of a whirlpool effect.

Unfortunately for fans of parks featuring quirky, well-landscaped and serpentine midways, the three largest attractions in the park are all located away from the rest of the layout in the middle of a big, cleared grassy field with long empty midways stretched between to connect them. My natural instinct is that this is the site of long-term future developments to eventually fill in the empty space, but if so they’re certainly taking their time as they started this expansion with the Bathtub Flume Ride in 1996 and then  G’sengte Sau in 1998, and haven’t added to it since until Mammut opened in 2008, extending the area of unfilled land back even further. Perhaps it’s useful for picnics and events during warmer months. Regardless, it hasn’t prevented them from applying an attention to detail to these three attractions that would be the envy of larger themers such as nearby Europa-Park.

G’sengte Sau in 1998, and haven’t added to it since until Mammut opened in 2008, extending the area of unfilled land back even further. Perhaps it’s useful for picnics and events during warmer months. Regardless, it hasn’t prevented them from applying an attention to detail to these three attractions that would be the envy of larger themers such as nearby Europa-Park.

First up is the Jungbrunnen (aka Bathtub Flume Ride) which honestly might be my favorite flume ride in the world. I only rode it once as it only operated for a couple hours in the afternoon and I didn’t want to risk getting any more wet from repeat rides, so I can’t remember every detail, but what I do remember is fairly impressive. Starting with the queue, which is practically better described as a museum with bathing artifacts as well as displays apparently concerning the mythology of the Fountain of Youth (as well as some other peculiar odds-and-ends), we eventually board our bathtub boat and then depart around a short flume, feeding us into the first small lift. A refreshing drop of about 25 feet or so gets things off to a good start. The channel curves us around

better described as a museum with bathing artifacts as well as displays apparently concerning the mythology of the Fountain of Youth (as well as some other peculiar odds-and-ends), we eventually board our bathtub boat and then depart around a short flume, feeding us into the first small lift. A refreshing drop of about 25 feet or so gets things off to a good start. The channel curves us around  indoors where another lift is approached, where at the top is a short dark ride section followed by a reversing mechanism feeding the tub directly into a backwards drop I was not anticipating. This next drop is apparently to ensure everyone in the boat, front or back, gets equally doused. Back outdoors, the flume meanders around a bit more before engaging the third conveyor lift which takes us all the way up to the maximum height. At the indoor section on the top is very large set displaying the Fountain of Youth, which includes about fifteen or so very anatomically correct nude female bathing figures. This is still a family ride in a family park, correct? Anyway, after this room we finish with the big drop which seemed steeper than most flume rides (they claim it’s the largest in Europe which I have a hard time believing). A splashdown which wasn’t too horribly wet and then back to the station.

indoors where another lift is approached, where at the top is a short dark ride section followed by a reversing mechanism feeding the tub directly into a backwards drop I was not anticipating. This next drop is apparently to ensure everyone in the boat, front or back, gets equally doused. Back outdoors, the flume meanders around a bit more before engaging the third conveyor lift which takes us all the way up to the maximum height. At the indoor section on the top is very large set displaying the Fountain of Youth, which includes about fifteen or so very anatomically correct nude female bathing figures. This is still a family ride in a family park, correct? Anyway, after this room we finish with the big drop which seemed steeper than most flume rides (they claim it’s the largest in Europe which I have a hard time believing). A splashdown which wasn’t too horribly wet and then back to the station.

Intertwined with parts of the flume structure is G’segnte Sau, Gerstlauer’s debut roller coaster creation and possibly the best non-spinning, single-car family roller coaster I’ve ever been on. Aside from the great landscaping and close flybys with the flume buildings and stone tunnels, it’s simply a complete ride. It fits so many different maneuvers into a logically organized progression sequence that’s normally only associated with massive, multi-million dollar signature attractions which are voted in top ten lists, not a quint little bi-rail family toboggan coaster, but yet it is. Let me bring out my old friend, the sequencing pattern analysis (see Fahrenheit, Thunderhawk, Millennium Force or Voyage for previous examples) to show you exactly what I mean:

(1 = banked spiraling drops/helices; 2 = switchbacks w/ laterals; 3 = airtime hills. Text darkness = intensity)

1 – 2 – 1 – 3 – 1

A simple and effective sequencing pattern, the beauty is that each number represents a radically different ride experience. Although it could be possible to take issue with a sequence that doesn’t end in climax, there’s regardless a sense of closure and satisfaction

A simple and effective sequencing pattern, the beauty is that each number represents a radically different ride experience. Although it could be possible to take issue with a sequence that doesn’t end in climax, there’s regardless a sense of closure and satisfaction with the last gentle, looping figure-eight that echoes the ride’s earliest moments. Having ride carriages which are super lightweight, open air and unobtrusive only helps to up the fun factor by many notches. The second, middle section can feel particularly intense when riding in such vulnerable cars. And then there’s the airtime hill sequence… why does it seem so rare for family rides to do airtime? After the rather hard laterals of the second part and the slightly scary spiraling intensity of the third, to get to the airtime sequence is such a joyful, happy way to start winding back down to the end. Special bonus points to Tripsdrill and Gerstlauer for the landscaped hills these bunny hops follow, and having the last airtime drop reach slightly further down into a trench than the rest. Made me slightly sad I missed Paulton’s Park’s version later that spring, but that one was without the landscaping and final helix.

with the last gentle, looping figure-eight that echoes the ride’s earliest moments. Having ride carriages which are super lightweight, open air and unobtrusive only helps to up the fun factor by many notches. The second, middle section can feel particularly intense when riding in such vulnerable cars. And then there’s the airtime hill sequence… why does it seem so rare for family rides to do airtime? After the rather hard laterals of the second part and the slightly scary spiraling intensity of the third, to get to the airtime sequence is such a joyful, happy way to start winding back down to the end. Special bonus points to Tripsdrill and Gerstlauer for the landscaped hills these bunny hops follow, and having the last airtime drop reach slightly further down into a trench than the rest. Made me slightly sad I missed Paulton’s Park’s version later that spring, but that one was without the landscaping and final helix.

So far I’m two-for-two with Tripsdrill’s large rides, now for their third and largest, Mammut. My gut feeling is that when looking to build Mammut, Tripsdrill originally talked to Great Coasters International about doing the job. It’s all there: curving first drop into a spectacularly banked fan curve, more high-banked, ground-level partial helices before a finale consisting of fast, back-and-forth directional changes. However, after being given an idea of a layout they really liked, were either unable to settle on a contract or simply needed to work with a local German firm instead. Either that or Tripsdrill just went to Stengel from the beginning and said “design us a wooden coaster like that!” (points to Thunderhead).

The ride, as you may know, was designed by Ingenieur Büro Stengel and built by Ingenieur-Holzbau Cordes (the same people responsible for bringing Intamin’s prefabricated wooden coaster technology to life; Intamin has no involvement with Mammut, however) and the result is pretty simply that: A GCI ride built as a Plug-n-Play. If you were to look up both of those terms in the dictionary of Things Coaster Enthusiasts Like, the result should have been orgasmic bliss, but instead it unfortunately serves to highlight the weaknesses of both with few of the advantages. Note the track doesn’t actually use prefabricated track, but the product seen here doesn’t feel that much further off except for allowing a bit more wiggle room for the wheel bases.

of those terms in the dictionary of Things Coaster Enthusiasts Like, the result should have been orgasmic bliss, but instead it unfortunately serves to highlight the weaknesses of both with few of the advantages. Note the track doesn’t actually use prefabricated track, but the product seen here doesn’t feel that much further off except for allowing a bit more wiggle room for the wheel bases.

The reason GCI’s style of layout with plenty of direction changes works is because it can feel out of control. Stengel is generally good at making rides ‘forceful’ or ‘fast-paced’, but unfortunately he seems yet to have developed a computer algorithm for ‘out-of-controlness’. Even in the case of Mammut, those two qualities that are present in rides such as El Toro were missing here. Most dearly absent were the little airtime pops that GCI tends to imbue in their transitions, here I only got a series of over-heartlined s-curves.

Most dearly absent were the little airtime pops that GCI tends to imbue in their transitions, here I only got a series of over-heartlined s-curves.

That’s not to say that these two concepts are both fundamentally incompatible in creating a top-tier wooden coaster, but when also factoring in the three-bench Gerstlauer cars, I’d hazard a guess that makes it especially tough. Not afforded the rotational flexibility of the single-bench Millennium Flyer cars, the transitions into high banking on Mammut are required to ‘sweep’ up and around (along the x and y axes) rather than ‘twist’ inline (along the z axis) as a GCI will do, which produces both slower pacing (more track length is required to reach a certain pitch) and more subdued dynamics which emphasizes light positive g’s over sharper laterals and fast rotational movement.

laterals and fast rotational movement.

Of course for this to be criticism rather than commentary, is to be presupposing the question that Tripsdrill even wanted a coaster as intense as a GCI or as forceful as a Intamin Prefab. Most likely they wanted a ride that was fun without being at all  scary for visitors apprehensive towards riding a wooden coaster (this was after all one of the first modern wooden coasters in the entire region). I will say at this they succeeded, as it manages to be a fun, easily reridable coaster, although moments like the airtime hill lacking anything of the sort do still lend slightly to a feeling of failed ambitions due to over-cautious engineering; it’s also entirely possible part of my lukewarm experiences with Mammut are due to it being the first day of the season and the trains had yet to warm up or break in yet. For a park the size of Tripsdrill this possibly the most perfect attraction they could have added since it’s a new signature ride but doesn’t exert unneeded dominance over the existing rides, the larger ambitions of a full-scale wood coaster standing about equal with G’sengte Sau’s greater

scary for visitors apprehensive towards riding a wooden coaster (this was after all one of the first modern wooden coasters in the entire region). I will say at this they succeeded, as it manages to be a fun, easily reridable coaster, although moments like the airtime hill lacking anything of the sort do still lend slightly to a feeling of failed ambitions due to over-cautious engineering; it’s also entirely possible part of my lukewarm experiences with Mammut are due to it being the first day of the season and the trains had yet to warm up or break in yet. For a park the size of Tripsdrill this possibly the most perfect attraction they could have added since it’s a new signature ride but doesn’t exert unneeded dominance over the existing rides, the larger ambitions of a full-scale wood coaster standing about equal with G’sengte Sau’s greater  relative success as a small family mouse.

relative success as a small family mouse.

This is also the first wooden coaster I’ve been on to feature a pre-show before the lift. A lumber mill with all sorts of lights, buzzers and switches going off with a saw buzzing overhead, the strangest effect was the fog they used for some reason shifted the light spectrum of the visible sky outside the tunnel to a greenish-yellow, the first time I rode momentarily making me think some really strange storm clouds had suddenly move in until we had cleared the fog and were back in open air. It wasn’t like the fog itself was yellow, it was just… weird. I have a premonition one of these days they’ll release medical findings that these types of theme park fog effects release a chemical causing neurodegeneration.

With a heavy rain storm coming in late that afternoon cutting the last hour of riding short, I had to call it quits for the riding and find the entrance. Before hopping on the bus to get to Haßloch that night, I need to go back and answer one of my original questions: is Tripsdrill an authentically German park, or is it a park themed to appear authentically German? This brings up a thorny issue in the argument between postmodernist social critics of theme parks and advocates for theme parks, in which the one side declares themed experiences to be superficial and fake, to which the other side points out that, ontologically speaking, theme parks are no less real than any of the things they are themed to. And this is extremely true. Whether you’re looking at the real Taj Mahal or a Styrofoam replica in Florida, both are extended objects made up of the same constituents that compose the fabric of the universe as any other object (although at the molecular level there’s a difference between extruded polystyrene foam and recrystallized carbonate minerals). Some of the better theme parks are so sophisticated that the items found within them are structurally identical to their real life counterparts, to the point that if taken out of their context they are indistinguishable from each other. After all, if Disney is to purchase a steam locomotive that once serviced the gold-mining areas of the Pacific Northwest, what’s to make that piece of equipment any less real once it’s relocated to sunny California and made to haul around paying tourists instead?

or a Styrofoam replica in Florida, both are extended objects made up of the same constituents that compose the fabric of the universe as any other object (although at the molecular level there’s a difference between extruded polystyrene foam and recrystallized carbonate minerals). Some of the better theme parks are so sophisticated that the items found within them are structurally identical to their real life counterparts, to the point that if taken out of their context they are indistinguishable from each other. After all, if Disney is to purchase a steam locomotive that once serviced the gold-mining areas of the Pacific Northwest, what’s to make that piece of equipment any less real once it’s relocated to sunny California and made to haul around paying tourists instead?

But still, anyone should intuitively realize that this is not what the theme park critic is arguing against. Clearly all objects have the same degree of ontological realness, so the idea of imitation must be about context, and describing the social or subject-object relationships that affect how people

But still, anyone should intuitively realize that this is not what the theme park critic is arguing against. Clearly all objects have the same degree of ontological realness, so the idea of imitation must be about context, and describing the social or subject-object relationships that affect how people viewed themed attractions differently from other structures. Perhaps it’s holding the simultaneous belief that an object is authentic while at the same time knowing that it’s been intentionally crafted by other people with the intent of deception which is what some people find problematic with theme parks. But that still leaves open the question of how does one separate the artificial from the real. If it’s a matter of context, then Tripsdrill would seem to be in the clear as it’s a German-themed park located in Germany. Logically that should neutralize any concept of themeing and turn the enterprise into a wholly authentic one, right? Then why do I still want to associate Tripsdrill more along the lines of theme parks like Disneyland Paris or PortAventura rather than locations authentically integrated with their local culture such as Knoebels or Tibidabo?

viewed themed attractions differently from other structures. Perhaps it’s holding the simultaneous belief that an object is authentic while at the same time knowing that it’s been intentionally crafted by other people with the intent of deception which is what some people find problematic with theme parks. But that still leaves open the question of how does one separate the artificial from the real. If it’s a matter of context, then Tripsdrill would seem to be in the clear as it’s a German-themed park located in Germany. Logically that should neutralize any concept of themeing and turn the enterprise into a wholly authentic one, right? Then why do I still want to associate Tripsdrill more along the lines of theme parks like Disneyland Paris or PortAventura rather than locations authentically integrated with their local culture such as Knoebels or Tibidabo?

I think a large part of what makes me want to label a park as authentic is that there’s an implied lack of choice and an absence of global awareness in their design. When looking at the layout and attention to detail present in Tripsdrill, it was clear that a hefty amount of calculation had gone into determining the precise look and feel of the park. If that is the case, then presumably one can conclude that, when designing a ride, equal effort would be exerted regardless if it were themed to Germany, Asia, the Old West, the Cretaceous Period, etc. What makes something feel authentic is if there’s a sense of necessity to its appearance which is external to the human calculation which built it. That is, you build stone walls in Ireland because those are the building materials you have access to, you grill mahi-mahi in Hawaii because that’s what you find in the water, and you build timber-framed restaurants which serve schnitzel and bratwurst in Germany not because you choose to theme it as such, but because given the environmental circumstances (this can extend as far as traditions, local tastes, etc.) that’s what people are required to do. That’s where cultures come from, isn’t it?

I think a large part of what makes me want to label a park as authentic is that there’s an implied lack of choice and an absence of global awareness in their design. When looking at the layout and attention to detail present in Tripsdrill, it was clear that a hefty amount of calculation had gone into determining the precise look and feel of the park. If that is the case, then presumably one can conclude that, when designing a ride, equal effort would be exerted regardless if it were themed to Germany, Asia, the Old West, the Cretaceous Period, etc. What makes something feel authentic is if there’s a sense of necessity to its appearance which is external to the human calculation which built it. That is, you build stone walls in Ireland because those are the building materials you have access to, you grill mahi-mahi in Hawaii because that’s what you find in the water, and you build timber-framed restaurants which serve schnitzel and bratwurst in Germany not because you choose to theme it as such, but because given the environmental circumstances (this can extend as far as traditions, local tastes, etc.) that’s what people are required to do. That’s where cultures come from, isn’t it?

This definition immediately presents some problems because it implies that for something to be authentic it has to be culturally isolated, and the number of places in the world where this is true is shrinking at an astonishing rate thanks to a little thing called globalization. It’s become assumed that any place in the industrialized has the money and resources to build their cities any style of their choosing. Pagodas in Paris? We have the knowledge base and resources to do it, so why not? Adobe cottages in Austria? Same applies, more or less. This argument seems to lead to the conclusion not that theme parks like Tripsdrill are as authentic as the cities that surround them, but that those cities are as fake as theme parks built to replicate them, as a necessary consequence of a fully globalized world in which cultural differentiation still exists.

This definition immediately presents some problems because it implies that for something to be authentic it has to be culturally isolated, and the number of places in the world where this is true is shrinking at an astonishing rate thanks to a little thing called globalization. It’s become assumed that any place in the industrialized has the money and resources to build their cities any style of their choosing. Pagodas in Paris? We have the knowledge base and resources to do it, so why not? Adobe cottages in Austria? Same applies, more or less. This argument seems to lead to the conclusion not that theme parks like Tripsdrill are as authentic as the cities that surround them, but that those cities are as fake as theme parks built to replicate them, as a necessary consequence of a fully globalized world in which cultural differentiation still exists.

I do think there’s a good deal of truth to this. In the fifty years since Disney the concept of ‘imitation’ or ‘hyper-reality’ has become so ingrained within worldwide cultures that it’s now impossible to separate that which is real from which is a façade; much of what defines a culture (especially American or others in developing markets) is the ways they imitate others, or even themselves. One of the phenomena I found most interesting during my time in Italy was how so much of the Italian culture I observed seemed to only be there for the sake of the tourists. Do you think the tableside violinist at a candlelit outdoor ristorante would still be playing Bella Notte if the tourists that came to Italy didn’t demand it? Of course not, they can play any other song composed from anywhere else in the world of their choosing. The entire city of Venice is today one giant tourist attraction; it doesn’t actually function as a working metropolis besides to generate travel revenue for the surrounding region. For a tourist, it’s becoming increasingly difficult to see the “real Italy” unimpeded; you instead have to settle for the real Italy as it attempts to simulate the “hyper-real Italy”.

from anywhere else in the world of their choosing. The entire city of Venice is today one giant tourist attraction; it doesn’t actually function as a working metropolis besides to generate travel revenue for the surrounding region. For a tourist, it’s becoming increasingly difficult to see the “real Italy” unimpeded; you instead have to settle for the real Italy as it attempts to simulate the “hyper-real Italy”.

Hold on, this criticism is being taken too far; I have a horrible feeling I missed an important and key consideration somewhere. Yes, it is true that Erlebnispark Tripsdrill is a theme park in all the ways I described above rather than some of the other parks I might describe as more ‘authentic’. However, it cannot possibly exist anywhere else in the world without losing the one feature that makes it a very special feeling place: the fact that it’s a proud statement of  identity for the people that built and operate it signifying that this heritage is so important to them that it’s worth building a theme park to celebrate.

identity for the people that built and operate it signifying that this heritage is so important to them that it’s worth building a theme park to celebrate.

Now THAT is something you can’t find just anywhere, Tripsdrill is one of the few parks in the world that has it, and an attempt to duplicate it anywhere else in the world would never yield the same results. The same goes for Italy or anywhere else in the world that maintains its unique appearance despite the fact that little extra effort would be required to transform it into something else. It’s not still an imitation like you find at Disney, the existential expression of identity is something very real and important, and that’s more or less what I think I can conclude Tripsdrill to be.

The animatronic people around the park were still creepy as shit, however.

Comments