Tongzhou, Beijing, China – Wednesday, April 24th, 2024

I’m always a little disappointed by leftovers for dinner. Invariably the texture and consistency isn’t as good as it was the first time around, and even for the few food categories that do keep and reheat well, there’s still the ennui of “I just did this recently.” But not everyone feels that way about their takeout the next day. Some people have a real talent for remixing components of yesterday’s meal into something fresh and exciting. Others may just be comforted by the simplicity of the old and familiar.

Universal Studios Beijing brings to mind a plate of Chinese leftovers. Half of the park are warmly reheated copies of lands and attractions found elsewhere; all of them good the first time, and perhaps slightly less impressive here. Half of the other remaining half are creative re-mixes using leftover ingredients, leaving only about a quarter of the plate being truly new, fresh ingredients. Assuming you’ve visited other Universal parks around the world, how you feel about Universal Beijing may depend on the attitude you carry to other things in life, such as your feelings about leftovers. To each their own.

Universal Studios Beijing brings to mind a plate of Chinese leftovers. Half of the park are warmly reheated copies of lands and attractions found elsewhere; all of them good the first time, and perhaps slightly less impressive here. Half of the other remaining half are creative re-mixes using leftover ingredients, leaving only about a quarter of the plate being truly new, fresh ingredients. Assuming you’ve visited other Universal parks around the world, how you feel about Universal Beijing may depend on the attitude you carry to other things in life, such as your feelings about leftovers. To each their own.

But I’ll note that even the plate itself, the park’s very existence in Beijing, seems a bit like Universal taking the leftovers of the Chinese market after Disney took the prime Shanghai (and Hong Kong) regions for themselves. That’s not meant as shade to Beijing itself; it’s absolutely an A-tier global city, and the rivalry between itself and Shanghai is well-matched. But as a city to host a major western theme park and media brand, it’s a bit of an odd fit. Shanghai (and Hong Kong) pride themselves on being very cosmopolitan, whereas Beijing is proudly the nexus of Chinese culture and politics. Its northern climate and suffocating seasonal smog1 also pose more of a challenge for outdoor entertainment than its more southern counterparts. Beijing absolutely deserves a major world-class theme park, and I believe Universal was correct that it would have been more successful claiming such an important metro market for themselves rather than trying to compete next door to the Mouse, as they must do stateside.2 Still, if you’re picking straws over who gets which major Chinese market capable of hosting an international theme park resort, it’s clear that Universal drew last.

They may have also drawn a little late. Universal Beijing hardly had the glamorous red-carpet debut they may have hoped for due to a delayed opening in the middle of the COVID pandemic. International visitors had few opportunities to see the new park until nearly two years after its debut when tourist visas were finally reinstated. Given China’s increasingly authoritarian backsliding that was exacerbated by COVID, the business wisdom of a major capital investment to access the Chinese market seems on less solid footing. If Universal had waited any longer on a mainland Chinese resort, I’m not certain it would have happened at all.

They may have also drawn a little late. Universal Beijing hardly had the glamorous red-carpet debut they may have hoped for due to a delayed opening in the middle of the COVID pandemic. International visitors had few opportunities to see the new park until nearly two years after its debut when tourist visas were finally reinstated. Given China’s increasingly authoritarian backsliding that was exacerbated by COVID, the business wisdom of a major capital investment to access the Chinese market seems on less solid footing. If Universal had waited any longer on a mainland Chinese resort, I’m not certain it would have happened at all.

To stretch this metaphor a little further, my own feeling towards Universal Beijing is far from an “essential Universal meal,” but also not quite “disappointing leftovers.” It’s more of a pleasant extra helping of Universal Parks that I didn’t need, but as long as it’s being served up I’ll gladly take it. It’s frankly a miracle this park got built at all, and fingers crossed that it finds its footing among the local population, and will continue to exist long into the future. Tomorrow is always a good option for more leftovers.3

Hollywood

The worst line of the day was getting in. When the park says they open at 10:00am, that means they start processing tickets at 10:00. No holding area in the Hollywood entry plaza prior. Despite arriving at 9:20am, there was already enough of a line that we didn’t actually get our tickets scanned until 10:40. The need to cross-check your ticket with ID (meaning you must carry your passport with you to the park) and scan your image for the facial recognition technology used throughout the resort slows things down considerably. Especially if you’ve grown a beard since your passport photo was last taken. So either get there very early or stay at an on-site hotel to enjoy the relatively quiet first half hour of the day as everyone else is still stuck at the front gate.

The worst line of the day was getting in. When the park says they open at 10:00am, that means they start processing tickets at 10:00. No holding area in the Hollywood entry plaza prior. Despite arriving at 9:20am, there was already enough of a line that we didn’t actually get our tickets scanned until 10:40. The need to cross-check your ticket with ID (meaning you must carry your passport with you to the park) and scan your image for the facial recognition technology used throughout the resort slows things down considerably. Especially if you’ve grown a beard since your passport photo was last taken. So either get there very early or stay at an on-site hotel to enjoy the relatively quiet first half hour of the day as everyone else is still stuck at the front gate.

Anyway, as can be expected at a Universal Studios park, on the other side of the ticket gates is a Hollywood zone. With its broad avenue and utilitarian shade canopy, Universal Beijing’s rendition emphasizes function over form. Having lived in Los Angeles for over a decade, I’m not certain if these romanticized Old Hollywood facades would theoretically resonate more or less with myself vs. an average Beijinger who’s never been to California. Regardless, they don’t resonate for me. While they try to find interesting colors and details to emphasize among the architectural vernacular, the facades are all too two-dimensional to have the energy of a real city. It gets us to the lagoon to start our day, and that’s about it.

That said, the Hollywood land does terminate into a very nice waterfront park that I appreciated getting to walk along. The views of Jurassic World (and to a lesser extend, Minions Land) generate plenty of excitement and photo opportunities, while not giving away the entire park in a single vantage point as happens at Islands of Adventure or Universal Studios Singapore. There’s still more to explore beyond.

Lights Camera Action!

A special effects show imported from Universal Studios Singapore, with an extended widescreen pre-show filmed for Beijing featuring directors Steven Spielberg and Zhang Yimou. It’s significantly more involved than the simple talking head format that features Spielberg at the E.T. Adventure, although their thesis message that soundstages are places where directors have complete control to let their imaginations run wild is somewhat undercut by the fact that most of their demonstrations are primarily CG, and neither Spielberg nor Zhang seem particularly enthusiastic or even aware of the action happening around them.

The main show is about two and a half minutes, taking place in a shipping yard as a major storm rolls in. The sequence of events is a little nonsensical. Rain pours in from the sealed roof, and things catch fire or fly across the room for seemingly no reason. The finale features a miniature steam ship pulling in through the bay doors and docking in front of us; toot toot. Uh, disaster? It’s clearly trying to adapt the beats of the classic Earthquake experience on the Universal Tram Tour, but is just missing the underlying logic and sense of danger that ties the sequence together in ever-escalating peril.

Apparently the show was a political challenge to produce, as local codes forbade Universal from open flames indoors. Rather than script a new experience that could work within the restrictions, Universal fought to keep the show as it exists in Singapore, working the authorities and calling in favors to eventually get an exception to the codes. A marvelous achievement given the way Chinese bureaucracy typically works, but I can’t help but wonder if simply removing roadblocks was preferable to finding creative new solutions to work around them?

Untrainable

This Broadway-style stage show based on Dreamwork’s How to Train Your Dragon franchise has been celebrated as one of the best new offerings at Universal Beijing; a similar show at Universal’s Epic Universe is one of the few elements that groundbreaking park will recycle from elsewhere. While live shows were further down my priority list with limited time, I knew this was a must-do.

Unfortunately the show was missing two things for me. The first was English captioning, which is understandably not included owing to the audience demographics, but I did feel I was missing a key element of the story that couldn’t be expressed visually or via tone and body language. The CliffNotes interpretation I got from my wife was that an untrainable dragon arrived in Berk, people were once again mad and fearful about the dragon, but Hiccup wanted to prove it was trainable, which it in fact was. Okay. Perhaps a little formulaic compared with other entries in the How to Train Your Dragon story world. Maybe understanding the missing nuance will resonate more when I experience it in Florida.

However the other big missing component was Toothless himself. I knew that the actor playing Hiccup riding a suspended Toothless puppet above the audience was the show’s big “wow” moment. I thus thought it odd when an early scene spent several minutes “flying” through fog and mapped projection clouds with nothing else happening. I kept eagerly awaiting for Toothless to appear, only to realize as the show was wrapping up that clearly there was some technical fault that forced our show into a Toothless-less B-mode. The rest of Untrainable clearly had promise (the untrainable dragon itself is also a very impressive puppet), but I unfortunately didn’t quite leave the theater walking on air.

Jurassic World: Isla Nublar

Universal Studios Singapore had the unfortunate luck of being built at an awkward time for the Jurassic franchise, with the original films all well on their way to legacy media that resulted in more conservative theme park offerings. Universal Studios Beijing, by contrast, came at a much more opportune moment, when the revamped Jurassic World had proven its box office bonafides as one of Universal’s top-performing in-house franchises, and executives were confident to green-light a much more ambitious program for their first ground-up theme park land based on the reinvigorated franchise.

The narrative of the Jurassic World films made clear that it is mutually exclusive from the classic Jurassic Park, so (almost) no mixing of the two here. And while Jurassic World is obviously the more timely franchise and current box office champion, it’s also, to put it bluntly, a worse film. Whereas the original films (and rides) were sci-fi cautionary tales about humankind’s hubris in the face of a chaotic and terrifying natural order, Jurassic World is simply a dumb old-fashioned monster movie, with a lumpy, formless, brown-grey antagonist as the new unstoppable monster baddie.

Fortunately, most of Jurassic World: Isla Nublar is a pretty good substitute for what works at the other Jurassic Park lands, only substituting red and yellow for blue and silver, bamboo and thatching for steel and concrete. On the downside, I wish the natural environment could be a bit more lush and rugged, but landscape architecture has never before been one of Universal’s strong suits, and that continues to be the case here. The primary two rides are likewise a bit of a mixed bag.

Jurassic World Adventure

If there’s a reason for a hardcore theme park fan to travel around the world to check off Universal Studios Beijing, I suspect Jurassic World Adventure will be at the top of that list. Spoiler alert: It was for me, and it largely succeeded.

Critical comparisons of the “Park” vs. “World” stories aside, Jurassic World Adventure is pretty close to what the best possible ride directly based on the Jurassic World film looks like. Not necessarily the best possible of all Jurassic rides (that’s still the now-defunct Jurassic Park: The Ride), nor the best possible ride that happens to have a Jurassic World theme (that’s VelociCoaster), but if you have to take the 2015 movie and translate it into a narrative-based ride, this might be the best possible outcome.

First up: the queue is great! That entry atrium not only looks architecturally impressive, but comes to life with well-produced media installations that almost made me wish we had a longer wait. The ride system is similar to Spider-Man and Transformers, only here you get an even larger reliance on practical sets and animatronics (a good thing given that a clone of Transformers is close by). This means it’s entirely indoor show sets, and is going to have a much faster pacing compared to the deliberate evolution from beauty to terror of the original Jurassic Park: The Ride.

The first scene may be the worst of the ride, an overly-squinched wraparound screen that tries to recall the wonder of the original JP: The Ride’s first encounter with the brachiosaur, but within seconds the mood is interrupted as something goes wrong. From then on it’s non-stop dino rampage with nary a moment to catch your breath.

The first scene may be the worst of the ride, an overly-squinched wraparound screen that tries to recall the wonder of the original JP: The Ride’s first encounter with the brachiosaur, but within seconds the mood is interrupted as something goes wrong. From then on it’s non-stop dino rampage with nary a moment to catch your breath.

The non-stop maximalism works because it puts in the effort to always surprise and astonish. There’s the most internet-famous moment when the Indominus Rex chases the ride vehicle along its pathway of motion via a clever turntable mechanism. It works so well you wonder how this is possibly the first theme park ride to think of it. Later on, life-sized I-Rex and T-Rex battle it out overhead, the sense of scale as you move between them very impressive. Yet one of the most effective stunts comes at the very end, when the I-Rex is pushed off screen, a split second later its physical head and neck violently snapping over an opening with surprising realism. The stunt is all the more effective for its brevity, avoiding the fallacy to “get their budget’s worth” by lingering at the animatronic for too long.

I won’t pretend that Jurassic World Adventure isn’t all just a dumb dinosaur spook house. But it does everything you want a big, loud theme park ride to do, and is generally very good at it… to a degree that puts many other big, loud theme park rides to shame. The level of craft is so high, and it’s so singularly good at eliciting that primal fear factor, it’d feel ridiculous to ask Jurassic World Adventure for deeper ideas or emotions.

Jurassic Flyers

As part of a theme park design team, to introduce the concept of “guest expectations” during a creative workshop, often someone in the room would cite this example: “If you’re doing the Jurassic Park ride and you don’t see any dinosaurs, you’ve failed guest expectations.” Stupidly simple. And yet, in Jurassic Flyers, that’s exactly what happened. Oops.

It’s not hard to trace the causal chain of how that happened. The first full Jurassic Park land opened at Islands of Adventure in 1999, and included a simple kid’s suspended pteranodon coaster circling the Camp Jurassic playground. It had low capacity that required strict rider height restrictions to manage demand, because despite being a simple C-tier attraction, everyone wants to fly with a pteranodon. It became a necessary component of all future Jurassic lands, even as the original manufacturer went out of business; Singapore’s system by SetPoint was bigger and beefier, but still subject to slow-moving queues; Japan’s B&M flyer was very high thrill and exclusionary to younger and more timid guests. Twenty-plus years later, Universal Beijing made the push for Mack’s suspended powered coaster, enabling a longer layout, higher capacity, and a still family-friendly experience that eluded all previous examples. Makes sense! But it’s also one of the most expensive and technologically advanced coaster systems on the market.

It’s not hard to trace the causal chain of how that happened. The first full Jurassic Park land opened at Islands of Adventure in 1999, and included a simple kid’s suspended pteranodon coaster circling the Camp Jurassic playground. It had low capacity that required strict rider height restrictions to manage demand, because despite being a simple C-tier attraction, everyone wants to fly with a pteranodon. It became a necessary component of all future Jurassic lands, even as the original manufacturer went out of business; Singapore’s system by SetPoint was bigger and beefier, but still subject to slow-moving queues; Japan’s B&M flyer was very high thrill and exclusionary to younger and more timid guests. Twenty-plus years later, Universal Beijing made the push for Mack’s suspended powered coaster, enabling a longer layout, higher capacity, and a still family-friendly experience that eluded all previous examples. Makes sense! But it’s also one of the most expensive and technologically advanced coaster systems on the market.

What was originally conceived of as a simple C-tier concept was promoted to an A-tier ride system. And park guests realize that! Even with its continuously loading platform, Jurassic Flyers routinely gets the longest lines in the park. It looks cool, and with its imposing mountain and waterfall seems to promise a lot! But there’s no pteranodons, or any other dinos. The vehicles can’t even represent dinosaurs, instead becoming robotic InGen conveyance things because they have to look realistically in-world somehow. There’s one spot in the caves that looks like a dino was intended to go there, but it’s left empty. The most exciting on-ride visual you get is a brief glimpse at the backside of water… wrong franchise! Even the moments that should just focus on the joy of flying through the enclosure are let down by an obtrusive catwalk system that seems like a late addition for compliance reasons.

Not every ride should be a blockbuster. I don’t know any serious theme park designers or fans who wouldn’t extol the virtues of the smaller, secondary attraction line-up. But you can’t just call one of the most expensive and technologically-advanced ride systems in the park a minor supporting attraction and expect guest expectations to also be set accordingly low. Jurassic Flyers clearly promises to be so much more, and it’s a disappointment when it feels held back by either a misallocated budget or by the mandate that this is only “supposed” to be a simple kids ride.

Transformers Metrobase

On the list of “things that are cool,” giant fighting robots must rank highly alongside giant fighting dinosaurs. Universal knows how to give the people what they want, even if it means paying other studios a license fee for their IP. In this case, the standalone Transformers ride has now been expanded into an entire land.

Look closely: it’s essentially a programmatic duplicate of Islands of Adventure’s Marvel Super Hero Island, minus the drop towers.4 When planning a new theme park, designers often have a very specific formula for how to make sure the attraction program is “balanced” amongst all interest types and demographics. It’s not uncommon for that formula to spit out the exact same set of rides even for completely different lands.

Look closely: it’s essentially a programmatic duplicate of Islands of Adventure’s Marvel Super Hero Island, minus the drop towers.4 When planning a new theme park, designers often have a very specific formula for how to make sure the attraction program is “balanced” amongst all interest types and demographics. It’s not uncommon for that formula to spit out the exact same set of rides even for completely different lands.

The land is very different, though. It’s less recognizable as a metropolis and more a collection of buildings and follies dripping with cyberpunk gak. I found a sign (on right) that nobly attempts a narrative justification of the look by imagining a larger sci-fi metrobase continuing deep under the surface, although it doesn’t explain why everything above ground is in a completely different style. It’s all ridiculously over-the-top, which in honesty is infinitely preferable to taking the material too seriously. As a franchise, Transformers has all-too-easily slipped into becoming a thinly veiled advertisement for the military-industrial complex. At least here, it’s not much more than an advertisement for brightly colored children’s car and robot toys.

Decepticoaster

As a clone of the ever-popular Incredible Hulk Coaster, the Decepticoaster makes some improvements (Vest restraints! Magnetic braking! Rad-looking launch tunnel! An only moderately inconvenient and poorly planned locker and metal detection setup!) while also showing some comparative weaknesses (Slightly slower launch! Worse soundtrack! Drab colors! Weird placement next to a forest that hides the first big inversions and makes them feel oddly much smaller! Theme and characters I don’t give a shit about!)

The thing that has me scratching my head is that, assuming this was in development around the same time as VelociCoaster, why didn’t we get a clone (or better, a new original layout) of that coaster instead? I like the Incredible Hulk perfectly well as an icon of the late-90s park it debuted at, but it’s not exactly at the vanguard of modern coaster design for the 2020s. It was developed at a time when coaster centerlines were primarily geared around an endless sequence of inversions and banked curves. Modern designs, even from B&M, now tend to incorporate a lot more element diversity, including sprinkles of negative G-forces throughout. That’s not just because enthusiasts love airtime. It was a necessary evolution for rider comfort, to prevent the continual onslaught of body-compressing positive G-forces from inhibiting blood circulation and causing disorientation, tunnel-vision, and nausea. They’ve tuned the launch speed down compared to Florida so it doesn’t have quite the same OMG factor around the first several elements, but it just means the rest of the positive-G focused layout is slightly duller and more drawn out. My wife rode once in the front row, and announced that was enough for her. Based on the five minute queue all day, I suspect she wasn’t alone. Even as the big draw for coaster enthusiasts, this feels like another example of this park getting yesterday’s leftovers. Even B&M lovers will find the nearby Happy Valley Beijing more than has their needs covered.

The thing that has me scratching my head is that, assuming this was in development around the same time as VelociCoaster, why didn’t we get a clone (or better, a new original layout) of that coaster instead? I like the Incredible Hulk perfectly well as an icon of the late-90s park it debuted at, but it’s not exactly at the vanguard of modern coaster design for the 2020s. It was developed at a time when coaster centerlines were primarily geared around an endless sequence of inversions and banked curves. Modern designs, even from B&M, now tend to incorporate a lot more element diversity, including sprinkles of negative G-forces throughout. That’s not just because enthusiasts love airtime. It was a necessary evolution for rider comfort, to prevent the continual onslaught of body-compressing positive G-forces from inhibiting blood circulation and causing disorientation, tunnel-vision, and nausea. They’ve tuned the launch speed down compared to Florida so it doesn’t have quite the same OMG factor around the first several elements, but it just means the rest of the positive-G focused layout is slightly duller and more drawn out. My wife rode once in the front row, and announced that was enough for her. Based on the five minute queue all day, I suspect she wasn’t alone. Even as the big draw for coaster enthusiasts, this feels like another example of this park getting yesterday’s leftovers. Even B&M lovers will find the nearby Happy Valley Beijing more than has their needs covered.

Transformers: Battle for the Allspark

I didn’t ride it. No single rider queue, and I wasn’t going to spend a half hour of my day on a copy of a ride I’ve ridden countless times at Universal Studios Hollywood and still don’t particularly like. But since I haven’t reviewed that park yet, I’ll include some brief thoughts on it here.

This ride needs music. For a while there was this trend that for a theme park to feel completely “real” and “immersive” it has to get rid of anything that could be perceived as artifice, and that includes non-diegetic soundtracks. Transformers: The Ride comes across so emotionally flat as a result. The Foley artists banging pots and pans are front-and-center in the final mix. If all the audio must be diegetic to the on-screen action (it’s nearly all screen-based), then why not make Bumblebee the guide to provide a lively pop soundtrack for all the scenes instead of just two brief cameos? It sure would beat Evac’s tedious narration of what’s happening in every scene.

Also, there’s a point where you’re “trapped” in a dead end tunnel, which we know because Evac announces we are. Yet the vehicle rotates to reveal this dead-end from the side where you can first clearly see the exit into the next scene. And it just seems representative of a ride where none of the story really matters and no one really cares.

Bumblebee Boogie

Previous attempts by Universal to include a teacups style flat ride5 were fairly lackluster, with names that promised speed and excitement but in reality were overbuilt variants of the carnival classic, heavily dampening the spinning on a short ride cycle. I was expecting the same from Bumblebee Boogie; yet while the ride hardware is fairly similar, I was pleasantly surprised that the thematic package has been upgraded so that this ride is actually fun to watch and to ride.

An impressively scaled, fluid-moving Bumblebee animatronic presides as a disc jockey at the center of the rotating turntable. A different pop soundtrack will play with each cycle, and the entire ride area lights up like a discotheque. At some point within the past decade theme parks realized that flat rides are more fun with lights and music, unlocking a deeply-held secret that was previously known only to dance clubs and kids birthday parties. The spinning wasn’t half bad either, although it’s far from Knott’s Mexican Hat Dance, but twirling under a disco ball may have helped. A dark horse candidate among the park’s five best rides.

Kung Fu Panda: Land of Awesomeness

Growing up, DreamWorks Animation was always the Pepsi to Pixar’s Coca-Cola; fine if it was the only option, but a little too saccharine in its quest to embed itself in the mainstream of popular culture, so you prefer the other brand whenever possible. Now with younger production companies like Illumination cranking those hyperactive qualities up to 11, DreamWorks has emerged as a more respectable grand dame of the CG animation industry, even if it still hasn’t managed to eclipse Pixar despite that studio’s recent woes.

even if it still hasn’t managed to eclipse Pixar despite that studio’s recent woes.

Yet despite Pixar being part of the Disney Parks behemoth, somehow DreamWorks has turned out surprisingly competitive in the themed attraction landscape that if forced to pick my preference, I would give serious consideration to DreamWorks’ offerings. This is primarily based on the strength of the wonderful DreamWorks indoor section of Motiongate Dubai, especially with its top-in-class Shrek dark ride and innovative HTTYD powered coaster. But Universal Creative was able to prove that wasn’t a one-off fluke of UAE economic incentives when they built their first immersive land based on a single DreamWorks property since NBCUniversal fully acquired the studio in 2016. Kung Fu Panda: Land of Awesomeness is, by some measure, the best land designed for Universal Studios Beijing. It even readily eclipses the Kung Fu Panda subzone of Motiongate (although still falls well short of the full four-zone package; Kung Fu Panda is generally considered the weakest of the four subzones at Motiongate’s DreamWorks land).

Land of Awesomeness is richly detailed, in a way that’s fun but not tacky or dumbed down. It even made me reconsider the film franchise in a more appreciative light. They use the indoor setting to their advantage, with dramatic lighting design and more delicate props and scenic details than is possible outdoors. Sometimes the budget gets blown on the building and the interior is little more than a decorated warehouse, but fortunately they didn’t fall into that trap here. I spent about an hour just exploring the environment, full of ambient elements including lanterns, statues, forts, waterfalls, bridges, and the ever-changing Peach Tree of Heavenly Wisdom (a mapped projection effect that wouldn’t feel out of place at a teamLab exhibit).

Land of Awesomeness is richly detailed, in a way that’s fun but not tacky or dumbed down. It even made me reconsider the film franchise in a more appreciative light. They use the indoor setting to their advantage, with dramatic lighting design and more delicate props and scenic details than is possible outdoors. Sometimes the budget gets blown on the building and the interior is little more than a decorated warehouse, but fortunately they didn’t fall into that trap here. I spent about an hour just exploring the environment, full of ambient elements including lanterns, statues, forts, waterfalls, bridges, and the ever-changing Peach Tree of Heavenly Wisdom (a mapped projection effect that wouldn’t feel out of place at a teamLab exhibit).

Rides also add to the ambience, including the Lantern of Legendary Legends, and the Carousel of Kung Fu Heroes. We ended up using the one lower-tier Express Pass included in our bundle in order to do the carousel, and I’m glad we did. The wooden character figures are funny and adorable, and further proof that modern IP can co-exist just fine with century-old classic amusement technology.

Kung Fu Panda: Journey of the Dragon Warrior

Oh dear. After lavishing praise on the land itself, I regret to inform you that its flagship attraction, the family dark water flume ride Kung Fu Panda: Journey of the Dragon Warrior, is not good. It seems likely a situation where the land show box and ride box were pulled from different budget pools, and the amounts were not distributed equally to their needs.

In the endless fan debate on the merits of animatronic figures over screens, Journey of the Dragon Warrior seems determined to put a plague upon both your houses. While the animatronics attempt a fuller range of motion compared to some cartoon-based rides that rely on simpler static figures, the result falls deep in the uncanny valley. Skin and fur don’t fit the bodies quite right; eyelids are too big for the eyes, which themselves seem to have gummed-up actuators that result in a distant, dead-eyed stare of a sleepless addict. Real nightmare stuff.

The middle section heralds the arrival of a screen-based sequence, which is something of a relief in as much as the characters now appear on-model and do kung-fu moves as you would expect from the films. But unfortunately this sequence is the worst excess of the “nothing but screens” mentality in dark ride design. Characters simply float and fight amid abstract backdrops that have no relation to the minimal scenic design surrounding it. Just a procession of big glowing rectangles presenting a story that is scarcely more involved than floating past a library of Kung Fu Panda-themed screensavers. A small drop into a media dome provides a brief kick of action near the end, but then you’re back to the creepy animatronics for the finale.

more involved than floating past a library of Kung Fu Panda-themed screensavers. A small drop into a media dome provides a brief kick of action near the end, but then you’re back to the creepy animatronics for the finale.

Where the ride does succeed is in capacity. I suspect that’s the whole reason it exists, because the park had to guarantee a certain minimum hourly capacity, and including a dual-station high-capacity boat ride that puts through 2500+ people per hour is one way to meet that quota while sticking to a budget. The empty, endless queue is a telltale sign of capacity planning gone awry; probably specified to hold something like two hours of queue during Lunar New Year, meaning around 5000 bodies at once. Hilariously, the biggest line of people always formed outside the queuing area spilling into the land itself, due to the presence of a single turnstile at the general entrance. Assuming one person can pass a turnstile every two to three seconds, that puts the hourly capacity of that turnstile at 1200 to 1800… well below the 2000+ I’d estimate the ride is capable of based on some back of the envelope figuring. Barring technical delays or an influx of Express users, it’s nearly impossible to imagine how that massive queue could ever fill. It was never anything other than a five minute posted wait during our visit.

WaterWorld

I get it, WaterWorld is a stunt show classic that should always be a part of the Universal Studios legacy. That’s a good reason for keeping it in Hollywood, but it doesn’t change how surreal it is to see a show based on Waterworld—Kevin Costner’s 1995 box office flop Waterworld!—being built anew in the Year of Our Lord Twenty-Twenty-One. I too wish theme parks could represent more of the classics within the film libraries of the media conglomerates that own them, but Waterworld is not one of them.

WaterWorld’s presence at Universal Beijing is not so much an argument for evergreen IP as it is that the IP is irrelevant. Universal happened to make a successful stunt show decades ago when a Waterworld tie-in was the mandate of the day, and now it seems the executives are scared to mess with the formula lest it turns out less successful, and the producers and other loyalists within the organization are scared lest it turn out more successful, thus mandating the rationally long-overdue updating to a more relevant film property at all locations.

I should say that we didn’t see the show. Just not a priority with limited time. It’s way out in the middle of an otherwise undeveloped plot of land at the back of the park, with enough room for a small themed plaza in front with some food and retail options. We did stop to get a bottle of water, which I suppose counts as a themed beverage experience!

The Wizarding World of Harry Potter

All previous Wizarding World locations had to fit into challenging sites at existing parks, which limited the options for controlling sightlines and guest flow. Universal Beijing is the first copy of the original Hogsmeade design to open at a new park, meaning they had complete control over how the land would be positioned in the rest of the park. The choice to locate it in the most remote corner with lots of undeveloped land around it suggests it may be intended as an anchor for future park expansions to build around.

Yet despite being given the freedom of a blank canvas, somehow Beijing’s Wizarding World is the most awkwardly fitted to its park. Approaching from Kung-Fu Panda/WaterWorld—it’s a loop park layout so anyone who’s progressing in clockwise order will take this route—you enter the land from the back and are presented with a clear view of the Forbidden Journey show building butting up to the back of Hogswarts Castle. I don’t consider myself an “immersion purist” by any means, but I had to take a moment when I realized how bad this view was as a first impression of their signature land.6

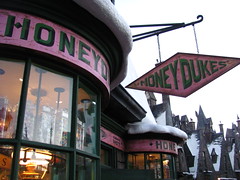

Once you’re inside it’s still the same immersive land you know and love (or hate, or are indifferent to), although I will note that the quality of finish in many of the details seems a little bit lower here than what you’ll find in the other installations. Graphic design details inside the shops are simplified or reduced, due to the need to either translate to Chinese or else only serve as decorative visuals in English. Gladrags Wizardwear gets a nice overhead installation that I didn’t recognize from Hollywood, although the floor space for Zonko’s has been completely eliminated in favor of more Honeydukes, awkwardly leaving only the exterior facade of the bright red joke shop that enters into a pastel-colored sweets store.

Once you’re inside it’s still the same immersive land you know and love (or hate, or are indifferent to), although I will note that the quality of finish in many of the details seems a little bit lower here than what you’ll find in the other installations. Graphic design details inside the shops are simplified or reduced, due to the need to either translate to Chinese or else only serve as decorative visuals in English. Gladrags Wizardwear gets a nice overhead installation that I didn’t recognize from Hollywood, although the floor space for Zonko’s has been completely eliminated in favor of more Honeydukes, awkwardly leaving only the exterior facade of the bright red joke shop that enters into a pastel-colored sweets store.

As a local to Universal Studios Hollywood, I was clearly not the target audience, as evidenced by the throngs of locals taking photos that far outstripped the popularity of the parks’ other lands. Pity those who buy a wand here with the intent of using it in this park, as nearly every interactive location had a queue formed for social media photo sessions instead. For me, I found the harsh Beijing sky—sunny, cloudless, yet with a faint gray haze over everything—made it difficult to take photos or feel the intended mood of the Scottish Highlands. We wouldn’t linger for too long.

Harry Potter and the Forbidden Journey

We probably would have skipped this, if not for having a Universal Express package that allowed us to avoid the posted 40 minute wait.7 One difference we found from the U.S. versions is that lockers are placed at the merge point for Express and standby. I’m not sure what the queue entailed before this point, but afterward there was only a staircase up the portrait gallery and then into the Sorting Hat hall onto the boarding platform. While offering lockers closer to loading is ostensibly a good idea, it evidently created a bottleneck that starved the loading platform, as we walked right up to the vehicle and observed a number of seats and benches being sent out empty. (Or else the 40 minute wait was a lie and we paid to skip the queue of a walk-on attraction.)

While offering lockers closer to loading is ostensibly a good idea, it evidently created a bottleneck that starved the loading platform, as we walked right up to the vehicle and observed a number of seats and benches being sent out empty. (Or else the 40 minute wait was a lie and we paid to skip the queue of a walk-on attraction.)

The ride itself is nearly identical to the Hollywood version I’m familiar with, except all dubbed in Mandarin. (Honestly, not understanding the dialogue may be an improvement.) Despite the depth of literary material it’s based on, the ride is still a spook house through and through, as it jumps between non sequitur scenes that make zero sense as a story but each works perfectly fine on its own as a theme park thrill. I find this “greatest hits” formula works better when it’s the only major Harry Potter ride in the park, since it has to do the heavy lifting for the entire franchise within a five minute ride time. Time will tell if Beijing’s stays isolated like Hollywood and Osaka’s Hogsmeades, or if the ample expansion plots surrounding it are used for more of Florida’s subsequent Wizarding Worlds to expand the story focus (and thus make Forbidden Journey’s frenetic catch-all style all the more unnecessary).

Flight of the Hippogriff

An off-the-shelf Vekoma junior coaster originally intended as a low-budget filler attraction in a forgotten park corner a quarter century ago, later given a fairly simple reskin when Comcast made its big, risky bet on the Potter franchise to pull the Universal Parks division out of its doldrums, has now become a seemingly non-negotiable component to all future Wizarding World installations, getting cloned three additional times by two different manufacturers.

Which is weird, because is Flight of the Hippogriff really that beloved by guests? It checks some boxes for demographic purposes, although with two other family coasters also included in the park, that rationale seems less essential in Beijing. Surely a family thrill coaster like Hagrid’s Magical Creatures Motorbike Adventure would make more demographic sense to fill the gap between Jurassic Flyers and Decepticoaster. As the fourth iteration of the Wizarding World, its success is all but guaranteed at this point, so the risk of a larger or custom secondary attraction seems more than justified. And there’s clearly more than enough room to build it. Sure, I can also see the justifications in favor of including another copy of Flight of the Hippogriff as the secondary attraction, but I’m curious if the discussion of something different was ever on the table at all?

Which is weird, because is Flight of the Hippogriff really that beloved by guests? It checks some boxes for demographic purposes, although with two other family coasters also included in the park, that rationale seems less essential in Beijing. Surely a family thrill coaster like Hagrid’s Magical Creatures Motorbike Adventure would make more demographic sense to fill the gap between Jurassic Flyers and Decepticoaster. As the fourth iteration of the Wizarding World, its success is all but guaranteed at this point, so the risk of a larger or custom secondary attraction seems more than justified. And there’s clearly more than enough room to build it. Sure, I can also see the justifications in favor of including another copy of Flight of the Hippogriff as the secondary attraction, but I’m curious if the discussion of something different was ever on the table at all?

Anyway, it’s the same experience as the Mack Rides version in Hollywood, except with a chain lift instead of a tire drive. Louder, but it also somehow feels more like a “real” coaster experience than a kid’s ride. With a 40 minute wait (that I paid to skip), it’s clearly a popular ride here. I hope guests find that wait worth their twenty seconds of swooping around in circles.

Minion Land

Part of my distaste for the Minions is how ruthlessly commercial they are. The pill shape, primary colors, interchangeable features, and slapstick, non-verbal humor are all transparently the product of an intellectual property lab tasked with creating the perfect children’s character that can be duplicated and sold in any context in any international market. I mean, I can admire the success of the Minions as the perfect pop-cultural objects, but I don’t have to personally like them. Because why would I give the marketers and other commodifiers of art that satisfaction?

Part of my distaste for the Minions is how ruthlessly commercial they are. The pill shape, primary colors, interchangeable features, and slapstick, non-verbal humor are all transparently the product of an intellectual property lab tasked with creating the perfect children’s character that can be duplicated and sold in any context in any international market. I mean, I can admire the success of the Minions as the perfect pop-cultural objects, but I don’t have to personally like them. Because why would I give the marketers and other commodifiers of art that satisfaction?

I’ll be honest, I didn’t even walk through the entirety of Universal Beijing’s Minion Land, now the largest in the world. The Universal on Parade parade was coming through during our allotted time in the land, and rather than fight the crowds to explore further, we decided to stay put and watch. From a distance it’s all the swirly pastels and taffy architecture I’d expect, with the added benefit of waterfront features. The indoor structure for the Super Silly Fun Land sub-zone at the center of the land is pretty utilitarian, and marks the third kid’s area in the park to be located indoors. Apparently children in Beijing are like gremlins and you can’t get them wet.

Loop-Dee Doop-Dee

Located in Super Silly Fun Land, this is a pretty similarly sized kids coaster as Flight of the Hippogriff, only this one was produced locally by Jinma Rides. I’ll hazard a guess there were some political stipulations that a certain amount of the park be made in China, and with so many specialized systems elsewhere, we get this slightly redundant filler attraction in Minions Land.

For what it’s worth, the hardware by Jinma handles capably, with the vehicle build and individual lapbars as robust as any comparable family coaster you’d find by Zamperla or the like. Where the ride is still not quite there compared to its western counterparts is in the centerline engineering. Curves are wide with very drawn-out transitions and gentle straight sections in between. It seems Jinma’s plan to maintain a smooth ride profile is to design as cautious of a layout as possible rather than figure out more advanced formulas. Also, there are no left turns in the entire layout. But technically this counts as one of Universal Studios Beijing’s completely original attractions, and after a twenty minute standby wait I got the fourth and final +1 to my coaster count.

Despicable Me: Minion Mayhem

Yet another copy and paste from the other Universal parks. I didn’t ride it in Beijing, as I had plenty of experience with the same simulator in Hollywood; itself an enlarged clone of the ride in Orlando that was the second overlay of The Funtastic World of Hanna-Barbera simulator from over thirty years prior. While being one of the most thoroughly reheated leftovers to reach Beijing, it’s also one of the most sensible. Minions are still extremely popular, and the ride film has a good mix of humor and peril within a forward-moving action setup that typifies successful theme park simulators. The dance party exit room is cute even if no one ever uses it. It gets a pass since this is mercifully the only motion simulator in this park after the much maligned Fast & Furious: Supercharged clone was cancelled.

Minions are still extremely popular, and the ride film has a good mix of humor and peril within a forward-moving action setup that typifies successful theme park simulators. The dance party exit room is cute even if no one ever uses it. It gets a pass since this is mercifully the only motion simulator in this park after the much maligned Fast & Furious: Supercharged clone was cancelled.

I don’t have much to add to this one, so I’ll just share a story about how I participated in the opening day ceremony of Despicable Me: Minion Mayhem at Hollywood in 2014. I helped wrangle the balloons that, at the climax of the ceremony, would all pop and throw yellow confetti over the audience. Unfortunately the balloon vendor had overfilled many of the balloons with helium, which as they warmed would continue to expand. Several of my balloons ended up popping at random times during opening remarks, and all I could do was just continue to stand there holding my now limp ropes with a sheepish “it wasn’t me!” look. I still have the yellow Minion construction hat I got to wear for the event in my closet. So I guess I still retain the smallest bit of sentimental attachment to this ride.

Conclusion

With the debut of Epic Universe likely ushering in a new age for Universal Destinations & Experiences, Universal Studios Beijing seems set to serve as a capstone for the post-Potter era of Universal theme parks. Everything here is competent, even if there are relatively few surprises. If I had to pick right now, this may be my bottom rated Universal park, simply because I like the coaster line-up at the more easily walkable Singapore park just a little bit more. But it’s also clear this park has gobs of room to grow in a way that its other Asian compatriots can’t, so it will be interesting to see if this park continues to get copies of proven attractions and lands from the other parks, or if like Universal Studios Japan it may find a niche that allows it to come into its own unique identity. Either way I’m glad I got to experience it near the beginning of its journey and will look forward to how it grows into the future.

Comments