Benidorm, Alicante, Spain – Sunday, May 9th, 2010

The day did not promise to be an easy one when it began in a slight panic over the realization that the Madrid Metro did not start service for the day until twenty minutes after I needed to be on it to get to the airport to catch a morning flight to Alicante. Running around like a headless chicken ensued in the massively modern Madrid-Barajas Airport, only to finally get to my terminal and find I had overestimated my time such that I still had a half hour before boarding procedures even started. Better safe than sorry, especially when adhering to a relatively strict travel itinerary without many additional resources in the event something should go wrong. From Madrid to Alicante by plane, from Alicante to Benidorm by coach (that would not turn off the Golden Oldies for the entire hour-long ride) from Benidorm to Terra Mítica by city bus,  this one hauling me back and forth across the city several times on a route all of three people made use of, I finally discovered the entry gates to the Land of Myth, and only an hour after park opening, too.

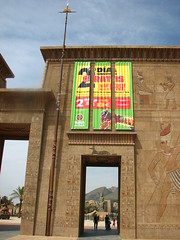

this one hauling me back and forth across the city several times on a route all of three people made use of, I finally discovered the entry gates to the Land of Myth, and only an hour after park opening, too.

It must be said first and foremost that the landscape surrounding the park is quite magnificent to behold, appearing almost like a piece of real life Roger Dean artwork with giant rock outcroppings far out over the sea with sheer cliffs walling the mountainous terrain separate from the calm, beachfront cove that Terra Mítica overlooks from its hillside perch. Contrasting this is the city of Benidorm itself, which is about as tacky as ‘tourist destinations’ get; think of a Spanish Myrtle Beach but with taller condominiums.

My initial impressions of the park left me with similarly mixed feelings: the towering Egyptian temples and ruins surrounding an expansive entry plaza scream overarching grandiosity but this drowns out the whisper of detail, so the 60 foot walls and columns of uniformly-colored sandstone plaster crafted a mise-en-scène that was oddly at once both intimidating and boring. These over-large entry plazas I generally find set themselves up for inevitable failure, as when they’re filled to the intended capacity and full of life and vitality, you moan and drag your feet because you know this means queues are going to suck all day, but when crowds are light (as they were today, and I suspect on the majority of days on Terra Mítica’s operating calendar) it only serves as a hollow and empty welcome to the park, like those old Hollywood sandals epics in which grand panoramas of the endless warmongering mob are at the sacrifice of any human-level intimacy (only without the mob). Some people love that style for the spectacle; I tend to prefer it when a park’s atmosphere is oriented more towards the tactile than the sublime, such that an appreciation is gained by stepping closer rather than stepping back.

I think my initial hesitancy towards Terra Mítica had less to do with its philosophy of aesthetic and more to do with the fact it appeared to be done a bit more cheaply than the vision required, and that both the quality and quantity of actual rides and attractions present would leave something to be desired. After walking ten minutes the only thing in the Egypt section I could find that even seemed worth contemplating a ride was a basic fairground-style Mack log flume spruced up with some themed tunnels and hillside terrain; I decided against it when I saw some people getting off completely drenched. Entering the Greek section I also gave a pass of Labyrinth of the Minotaur for the moment along with a few other odds and ends, to make the Vekoma SLC Titánide way in the back right corner of the park my first ride of the day.

the back right corner of the park my first ride of the day.

I might very well be the best friend the SLCs have, defending them on several occasions for having a dynamic, well-paced and well-sequenced layout (at least until the last barrel roll) and not being nearly as rough or uncomfortable as many make them out to be, in many cases a superior ride to similarly sized B&M inverts.

Titánide was not my friend, for a few reasons. First, it’s rough. Maybe my luck just finally ran out. As much of the problem came from the train’s bogies rattling around on the track as the extra restricting restraints on the train, with two large puffs of foam on the inside, apparently intended to prevent one’s head from moving at all as well as to grab hold and threaten theft of my glasses when the restraints were finally lifted. Parks and designers take note: a rough ride is not made more comfortable by further restricting bodies when they’re being jolted about, especially when the device that’s  doing the restricting is also doing the jolting.

doing the restricting is also doing the jolting.

But second, and perhaps even more egregious, it did almost nothing for a park that’s already short on quality signature attractions. Oddly connected to the main midways in the back corner of the park on a level plot of gravel land that, given the hilly surroundings was clearly not level before it moved it, it’s one of those rides that’s left with an awful ‘carnival coaster’ aesthetic in a park that should be better than that. What’s most disappointing about this is that it’s relatively new to calling the Greek section of the park its home. It was previously located at the bottom of the hill on the opposite corner of the park in the Iberian theme zone under the name Tizona (also much easier to pronounce and remember… “Titánide” sounds like what you’d use to poison a porn star), and from what I can see on the RCDb it appeared to be much better presented there. Built over naturally flat land in front of the lagoon with a much better thematic integration and presentation, it was also the only major attraction that entire corner of the park had. The removal of this coaster effectively kills Iberia (most of which is now shuttered) while it overstuffs Greece which was already the densest midway and is where the most bottlenecking is likely to occur. The only sane explanation I can think of for this relocation and condemnation of a large chunk of the park would be a local ordinance requiring them to move the loud attractions away from area residents (I didn’t notice any housing nearby the park), otherwise the choice financially struggling park to disassemble, transport, repour foundations and reroute the infrastructural connections, and then reassemble a coaster in a new location that’s worse than the previous, even if they might save money by closing an underutilized theme zone, seems nothing short of madness.

of the park had. The removal of this coaster effectively kills Iberia (most of which is now shuttered) while it overstuffs Greece which was already the densest midway and is where the most bottlenecking is likely to occur. The only sane explanation I can think of for this relocation and condemnation of a large chunk of the park would be a local ordinance requiring them to move the loud attractions away from area residents (I didn’t notice any housing nearby the park), otherwise the choice financially struggling park to disassemble, transport, repour foundations and reroute the infrastructural connections, and then reassemble a coaster in a new location that’s worse than the previous, even if they might save money by closing an underutilized theme zone, seems nothing short of madness.

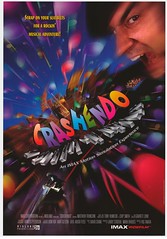

Nearby was a pantheon-like structure called the Templo de Kinetos which I gathered likely housed a simulator inside. Indeed my suspicions were correct, but rather than an expected Greek spectacle I got sent much further back in time: to the mid 90’s. The film was the thematically idiosyncratic Crashendo, where a runaway piano careens down a hill and through sunny California city streets while the pianist struggles to both finish the song and keep his musical instrument from crashing into oncoming traffic. I remember first seeing a clip of this on TV way back around 1996, and finally getting a chance to watch the entire film was a genuinely surprising treasure. I think the show was part of a Thrills, Chills and Spills summer special, but couldn’t find any archives online; I did find the similarly oriented Theme Parks A-Go-Go on YouTube which proved a goofy nostalgia trip for a time when Arrow coasters were still getting the lion’s share of media attention, especially if you grew up without the internet and learned everything about theme parks through worn books , brochures and VHS recorded TV specials.

, brochures and VHS recorded TV specials.

Simulators are a dead ride form, everyone two decades ago thought they were going to be the next big thing because they could supposedly take riders anywhere, but in reality watching a fixed-POV, low-budget computer generated video with seats bouncing around did the complete opposite. However, if more had been produced with films like this, then they may have lasted just a little bit longer. Filmed as live action at least meant I was appreciative of the technical skill it took to choreograph that many stunts over a long single take with a constantly moving camera (especially without any computer effects or enhancements), and in addition to simply being a surreally over-the-top premise, having a comedic actor as a ‘protagonist’ of sorts allows the audience a real connection to the world of the film (no matter how realistically rendered, CG dinosaurs chasing after us are not real, but a wily comic routine always is). My favorite motion simulator I’ve ever been on, not that I was inclined to ever do it a second time that day.

SynKope was a Mondial Revolution spinning pendulum ride situated over the hillside which seemed to be more popular with the local guest population than the experience actually warranted, but then again I’m used to larger versions of this same ride, and the views were quite nice. Nearby Los Ícaros was another flat ride (this one a simple chair swing) that also made good use of its location along the edge of a large ridge. La Furia de Tritón was a large shoot-the-chutes splashdown flume ride which appeared to have a long layout with at least two drops and a few tunnels winding up and around the rocky cliff sides, a very promising ride I was about to join the queue for before I realized that the majority of people getting off were completely soaked through and through.

SynKope was a Mondial Revolution spinning pendulum ride situated over the hillside which seemed to be more popular with the local guest population than the experience actually warranted, but then again I’m used to larger versions of this same ride, and the views were quite nice. Nearby Los Ícaros was another flat ride (this one a simple chair swing) that also made good use of its location along the edge of a large ridge. La Furia de Tritón was a large shoot-the-chutes splashdown flume ride which appeared to have a long layout with at least two drops and a few tunnels winding up and around the rocky cliff sides, a very promising ride I was about to join the queue for before I realized that the majority of people getting off were completely soaked through and through.

Instead I ended up at Alucinakis, a steel children’s roller coaster (derived from Zamperla’s Family Gravity Coaster) with a custom layout and wooden support structure, intended to be the miniature version of Magnus Colossus, even though that one’s in Rome and this is still in the Greek area. It was a pleasant little coaster, and like the other nearby flat rides aided by its hillside perch overlooking the rest of the park and the valley. The ride’s main deficiency was that much of the track was too flat and gradual. This missed the primary advantage of small children’s coasters which is that they can have much tighter, more intense track than larger coasters without getting excessively large G-forces, although I suspect perhaps that is the tone of ride they were intending.

intending.

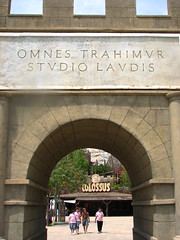

Crossing a bridge far above a wooded river valley, I made my way through the Aurelian Gates and into my recently former home of Roma, the miniature theme park ancient edition, that is. Directly ahead was the entrance to Terra Mítica’s signature attraction, Magnus Colossus. The queue and station were built almost entirely by untreated fallen timbers to replicate the fortresses on a Roman battlefield, the natural weathered appearance with a unique station design (the queue loops around an upper deck inside the station, the walls are solid and prevent spectatorship of the coaster we’re about to ride, but the top is completely open-air letting the sun take the place of any artificial lighting) all evokes a strangely real and distinct sense of place and timelessness. The rolling stock are made by Intamin, the hydraulic T-bar restraint a non-plus but at least the rest of the car configurations are more in line with a traditional PTC style design rather than the pre-fab cars on the non-pre-fabbed Coaster Express a day earlier.

the fortresses on a Roman battlefield, the natural weathered appearance with a unique station design (the queue loops around an upper deck inside the station, the walls are solid and prevent spectatorship of the coaster we’re about to ride, but the top is completely open-air letting the sun take the place of any artificial lighting) all evokes a strangely real and distinct sense of place and timelessness. The rolling stock are made by Intamin, the hydraulic T-bar restraint a non-plus but at least the rest of the car configurations are more in line with a traditional PTC style design rather than the pre-fab cars on the non-pre-fabbed Coaster Express a day earlier.

Buckled in and departing through the timber battlements, the first lift hoisting us up two levels of stony cliffs as we eyeball up close the massive wooden structure and double dip first drop, the layout promises the beginnings of a top-tier wooden coaster adventure. Reaching the apex, a slow turn at ground level builds anticipation as the cars inch closer to the edge of mayhem. Had this been designed by CCI I might have been on the edge of true wooden coaster greatness. Unfortunately, Terra Mítica contracted with RCCA instead (they of Coaster Express and Son of Beast infamy), perhaps out of necessity as CCI already had eight projects that and likely couldn’t go to Europe as well, and/or from an engineering standpoint RCCA may have offered a slightly more sound proposal than CCI’s quick and on-the-cheap methods. Regardless, with this bit of a priori knowledge I was prepared not to expect too much, as there was a good chance it would be rough as sandpaper and the oversized layout would be precisely that: larger and more drawn out that it should have been, such that the only forces to be felt during the ride would be from the cars giving my lumbar an aggressive massage.

Buckled in and departing through the timber battlements, the first lift hoisting us up two levels of stony cliffs as we eyeball up close the massive wooden structure and double dip first drop, the layout promises the beginnings of a top-tier wooden coaster adventure. Reaching the apex, a slow turn at ground level builds anticipation as the cars inch closer to the edge of mayhem. Had this been designed by CCI I might have been on the edge of true wooden coaster greatness. Unfortunately, Terra Mítica contracted with RCCA instead (they of Coaster Express and Son of Beast infamy), perhaps out of necessity as CCI already had eight projects that and likely couldn’t go to Europe as well, and/or from an engineering standpoint RCCA may have offered a slightly more sound proposal than CCI’s quick and on-the-cheap methods. Regardless, with this bit of a priori knowledge I was prepared not to expect too much, as there was a good chance it would be rough as sandpaper and the oversized layout would be precisely that: larger and more drawn out that it should have been, such that the only forces to be felt during the ride would be from the cars giving my lumbar an aggressive massage.

The double first drop however does open the ride promisingly. The pullovers are much wider than they need to be, but they’re almost designed such that the rate of steepness actually increases as they go on from the very gradual lead-in, producing at least an interesting inner-ear falling sensation if not exactly any airtime yet. The second drop is a repeat of the first only much faster. Airtime seems to be light, but a sudden downward jolt launches everyone (especially those in the back of the train) sky-high out of their seats, the only genuinely forceful and intense moment of the ride. Combined with the highest rate of speed on the pullout, a genuine sense of dread is created in wondering if this ride might literally be dangerous to us, the rattling cars threatening derailment should anything more unexpected be around the next bend.

derailment should anything more unexpected be around the next bend.

Instead the cars roar around a large double fan turn, burning off a lot of speed as it returns to the first elevated level of the quarry. A small rise into a hill produces a large drop-off back down the cliff, the train once again shimmering with malicious intent but without any actual danger to our health. Curving back up the cliffs near the first drop, it takes a moment’s mid-ride pause with a flat turn and another long, slow lead-up to the edge of the cliff, mimicking the anticipatory build-up from the start of the layout and suggesting the commencement of an act two. This drop-off unfortunately doesn’t quite live up to that promise, rising into a wide, slow helix that does nothing besides demonstrate how much of a shuffle these Intamin cars have. Towards the end it starts to gain speed, accumulating at long last laterals which suggest something interesting is around the next bend as a grand finale, only to disappointingly discover that was the finale

unfortunately doesn’t quite live up to that promise, rising into a wide, slow helix that does nothing besides demonstrate how much of a shuffle these Intamin cars have. Towards the end it starts to gain speed, accumulating at long last laterals which suggest something interesting is around the next bend as a grand finale, only to disappointingly discover that was the finale as the train slides into the magnetic brake run.

as the train slides into the magnetic brake run.

Ultimately I would say I enjoyed Magnus Colossus for several reasons. The roughness felt like how a wooden coaster was supposed to feel without being aggressive beyond the point that a marathon re-riding session later in the afternoon would be untenable. The double drop was a pretty good opening, and the use of the excavated cliff walls meant it achieved an interesting sequencing of shallow and long drops (as well as low and high speeds), unlike on nearly every other roller coaster where the drops must only get shallower as the ride progresses. Unfortunately these positive traits (which possibly makes it the best wooden coaster in Spain, or at least the most original the country has to offer) only mask how much more potential it would have had if RCCA not been so timid with the rest of the layout. Most disappointing about this is that looking at the imposing structure, one realizes that this conservativeness only resulted in an extravagant wastefulness of resources, as mountains of dense supports accomplish almost nothing for the rider, while a sparser approach like CCI would have given it the sharper drops and narrower curves it so desperately calls for.

and long drops (as well as low and high speeds), unlike on nearly every other roller coaster where the drops must only get shallower as the ride progresses. Unfortunately these positive traits (which possibly makes it the best wooden coaster in Spain, or at least the most original the country has to offer) only mask how much more potential it would have had if RCCA not been so timid with the rest of the layout. Most disappointing about this is that looking at the imposing structure, one realizes that this conservativeness only resulted in an extravagant wastefulness of resources, as mountains of dense supports accomplish almost nothing for the rider, while a sparser approach like CCI would have given it the sharper drops and narrower curves it so desperately calls for.

Down the trail a bit further was the park’s newest, and arguably their best roller coaster (as well as my first 4th dimension coaster), the Intamin-designed ZacSpin Inferno. This odd compact coaster is built using all of six footings (two of which are just for bracing). Small, but fun seems a good way to quickly describe it. While three cars are permanently attached to the track they were only loading one and sending the other two around empty due to the low crowd turnout, a minor annoyance as this made re-rides without walking around the queue again impossible.

The restraints use the new shoulder straps that people are requesting to be retrofitted to every other Intamin OTSH design. While sure to reduce headbanging (which given the number of twists and turns in this layout was surely a major factor in their implementation) they were also significantly more snug and made any degree of leaning forward impossible. An interesting thought occurred, how many inversions could this coaster be counted as having? None, as the RCDb claims? Two, as is the number of times the track goes from face down to face up? Or one, the average amount of times the cars would actually invert their riders, usually on the last little spike? As I was often a single rider this meant the car would be unequally weighted and I’d be staring up at the sky most of the time, a minor frustration as this often prevented the rotational momentum needed to get a complete 360° flip.

Intamin OTSH design. While sure to reduce headbanging (which given the number of twists and turns in this layout was surely a major factor in their implementation) they were also significantly more snug and made any degree of leaning forward impossible. An interesting thought occurred, how many inversions could this coaster be counted as having? None, as the RCDb claims? Two, as is the number of times the track goes from face down to face up? Or one, the average amount of times the cars would actually invert their riders, usually on the last little spike? As I was often a single rider this meant the car would be unequally weighted and I’d be staring up at the sky most of the time, a minor frustration as this often prevented the rotational momentum needed to get a complete 360° flip.

After an odd C-shaped lift equipped with a double chain similar to that on Fahrenheit, this coaster basically goes through all the motions of a good roller coaster dramatic progression in the fifteen seconds it takes to go from crest to brakes. A moment of slow anticipation at the top, a very sudden drop off to kick things into gear, development with a second plummet

After an odd C-shaped lift equipped with a double chain similar to that on Fahrenheit, this coaster basically goes through all the motions of a good roller coaster dramatic progression in the fifteen seconds it takes to go from crest to brakes. A moment of slow anticipation at the top, a very sudden drop off to kick things into gear, development with a second plummet into the highest-speed valley, and the grand finale with the aforementioned phallic spike that we try to get to turn us upside down. On some rare instances the cars would become stuck upside down and the operators would have to right it on return to the station. Random magnetic scarf brakes along the course also give a bit of play in our seats’ directionality relative to the earth. I’d like to see more of these at small parks around the world as besides being fun, bizarre and fairly intense for the short layout,

into the highest-speed valley, and the grand finale with the aforementioned phallic spike that we try to get to turn us upside down. On some rare instances the cars would become stuck upside down and the operators would have to right it on return to the station. Random magnetic scarf brakes along the course also give a bit of play in our seats’ directionality relative to the earth. I’d like to see more of these at small parks around the world as besides being fun, bizarre and fairly intense for the short layout, the unpredictable nature of the vehicles (as well as choice between sitting forward or backward and on the left or right side) makes rerides when queues are short highly rewarding.

the unpredictable nature of the vehicles (as well as choice between sitting forward or backward and on the left or right side) makes rerides when queues are short highly rewarding.

Yet further down the Appian Way we finally enter the more grandiose themeing of the Roman capital, which contains a few shows, restaurants and rides, although only one I found worth waiting for, El Vuelo del Fénix (Flight of the Phoenix), an Intamin second-gen drop tower. Honestly I’m running out of commentary to say about these tower rides which seem to be installed at every park so I’ll just relay this totally unrelated joke instead: Compared to Spanish or Italian, English must surely seem a strange tongue. For instance, how do you explain to someone learning the language why it’s okay to “prick your finger” in public, but then not okay to “finger your prick”? (Credits to the late George Carlin for that one, possibly the greatest commentator on the oddities of the English language.)

The other end of Rome led to a locked-off gate which appeared to lead to a significant portion of the park. This was the rest of the currently too-small Iberia section which Titánide once called home (and called itself Tizona). A shame because it looked like a genuinely pleasant midway, one I’m disappointed I didn’t have the chance to further explore. I would like to say right now that by this time I had totally reversed my initial somewhat negative opinions of the park stated toward the beginning of this essay. Yeah, the theme maybe was lacking in the same degree of detail that some other parks put in, but it was certainly at no loss of ambition. That doesn’t even really matter, because I’m almost never one to praise themeing for themeing’s sake anyway. What I found was that when the designers let the natural topography

The other end of Rome led to a locked-off gate which appeared to lead to a significant portion of the park. This was the rest of the currently too-small Iberia section which Titánide once called home (and called itself Tizona). A shame because it looked like a genuinely pleasant midway, one I’m disappointed I didn’t have the chance to further explore. I would like to say right now that by this time I had totally reversed my initial somewhat negative opinions of the park stated toward the beginning of this essay. Yeah, the theme maybe was lacking in the same degree of detail that some other parks put in, but it was certainly at no loss of ambition. That doesn’t even really matter, because I’m almost never one to praise themeing for themeing’s sake anyway. What I found was that when the designers let the natural topography and foliage of the land take precedence in painting the vistas, with their own work just supplying the accents around the edges, the results were truly inspired at times, with much of it even representing the ‘ideal’ approach I would take towards a theme park, above even the billion dollar expenditures of a place like Disney. There’s an organic quality to Terra Mítica rarely apparent in other parks, such that the creative blueprints feel collaborative with the outside environment rather than suppressive towards it. What’s better, nearly everything I saw inside its gates felt completely original to Terra Mítica and not simply mimicking the standard set by Disney for “how theme parks are supposed to look”. No radial infrastructure around a centerpiece lagoon or monument, no Wild West zone, no cartoon mascots, no “it’s a small world” or Pirates of the Caribbean

and foliage of the land take precedence in painting the vistas, with their own work just supplying the accents around the edges, the results were truly inspired at times, with much of it even representing the ‘ideal’ approach I would take towards a theme park, above even the billion dollar expenditures of a place like Disney. There’s an organic quality to Terra Mítica rarely apparent in other parks, such that the creative blueprints feel collaborative with the outside environment rather than suppressive towards it. What’s better, nearly everything I saw inside its gates felt completely original to Terra Mítica and not simply mimicking the standard set by Disney for “how theme parks are supposed to look”. No radial infrastructure around a centerpiece lagoon or monument, no Wild West zone, no cartoon mascots, no “it’s a small world” or Pirates of the Caribbean rip-offs. It’s not a look that immediately leaps out of one’s imagination, but after enough time I found I would hardly rather be anywhere else. By the end of the day it got my vote for favorite European theme park (i.e. judged only for the quality of the thematic setting itself), perhaps alongside the even more off-beat Erlebnispark Tripsdrill.

rip-offs. It’s not a look that immediately leaps out of one’s imagination, but after enough time I found I would hardly rather be anywhere else. By the end of the day it got my vote for favorite European theme park (i.e. judged only for the quality of the thematic setting itself), perhaps alongside the even more off-beat Erlebnispark Tripsdrill.

My day wasn’t over yet. I still had several more sections of the park to explore: what’s left of Iberia, ‘The Islands’, and Ocionía, unfortunately none of them with any notable attractions, or even very distinctive from each other. The first thing I did was La Cólera de Akiles (The Anger of Achilles), a Mondial-built ride reminiscent of a HUSS topspin but providing a markedly different experience. The gondola is loaded in rows front to back like a coaster train, and while it does no inverting the two arms at either end spin independently of each other, one arm with a flexible bend in it to allow for this changing distance. Unfortunately it’s a bit of a snoozer by comparison, as when the two arms would get going in opposite directions this meant the middle of the gondola would only gyrate around a fixed point, the motions were most interesting when the two arms got together in moving the same direction, and then it was just like a Top Spin but without the inverted flipping. I gave a pass to Los Rápidos de Argos, again because I didn’t want to risk getting wet, but somehow missed the area’s second river raft ride El Rescate de Ulises, apparently all indoors. As far as I could tell Ocionía was just an extention of either the Islands or Egypt, as the only thing listed to the area I bothered trying was the Intamin-made Infinnito sky tower ride, which offered some nice views of the surrounding area. Much picture taking ensued; unfortunately it wasn’t until a day later when I realized my camera’s lens had a large water spot on it all day.

spin independently of each other, one arm with a flexible bend in it to allow for this changing distance. Unfortunately it’s a bit of a snoozer by comparison, as when the two arms would get going in opposite directions this meant the middle of the gondola would only gyrate around a fixed point, the motions were most interesting when the two arms got together in moving the same direction, and then it was just like a Top Spin but without the inverted flipping. I gave a pass to Los Rápidos de Argos, again because I didn’t want to risk getting wet, but somehow missed the area’s second river raft ride El Rescate de Ulises, apparently all indoors. As far as I could tell Ocionía was just an extention of either the Islands or Egypt, as the only thing listed to the area I bothered trying was the Intamin-made Infinnito sky tower ride, which offered some nice views of the surrounding area. Much picture taking ensued; unfortunately it wasn’t until a day later when I realized my camera’s lens had a large water spot on it all day.

On my second lap around the park I still had one more major attraction to try: El Laberinto del Minotauro (Labyrinth of the Minotaur) a Sally interactive dark ride. After my first ride, I quite honestly believed I may have just experienced the best modern dark ride still operating in the world. Here’s why.

On my second lap around the park I still had one more major attraction to try: El Laberinto del Minotauro (Labyrinth of the Minotaur) a Sally interactive dark ride. After my first ride, I quite honestly believed I may have just experienced the best modern dark ride still operating in the world. Here’s why.

First of all, “the attention to detail in the set designs is stunning.” By itself that really means nothing, but it’s a cliché in theme park reviews that apparently holds some intrinsic value even when left unqualified for many readers, so I will start with that. Sally really went above and beyond anything else I’ve seen from them in creating not just elaborately-constructed monsters with realistic hair, scales, eyes and fangs, but in creating so many monsters, and in an immersive environment that did not let them down. What makes this important is that actual creative labor was involved in its construction; the idea didn’t come prepackaged with an intellectual property by the parent company or as a rip-off from another park’s successful attraction. Despite the long ride time and numerous scenes, the attraction never becomes redundant, with more flavors of mythical beasts than found in the average Guillermo del Toro movie.

“Is it as good as Disney?” This seems to be the common measuring stick for themed dark ride. I answer with: “It’s better than Disney!” While granted they didn’t have quite as large of a budget or technological pool to draw resources from, in many ways I think that was an advantage. For one thing, I was able to stop leaning forward in wonderment of “how did they do that?” and was able to lean back and wonder “what are they trying to do with all of this?” The Disney dark rides I’ve tried (especially Phantom Manor) can feel harried and cluttered with one technological gimmick after another, while Sally slows the pace down and gives each scene a central focus point as well as time for the eerie atmosphere to breathe. This is partly accomplished by the fact that they don’t need a capacity of 3000 people per hour, so rather than use a chain of vehicles requiring that all the showrooms and animatronics be on a continuous loop so every visitor can view them at once, individualized trackless cars are utilized allowing everything in each scene unfolds itself directly to you, creating an urgency and intimacy not found on other dark rides, as well as fostering in micro-narratives such that it doesn’t become a monotonous

need a capacity of 3000 people per hour, so rather than use a chain of vehicles requiring that all the showrooms and animatronics be on a continuous loop so every visitor can view them at once, individualized trackless cars are utilized allowing everything in each scene unfolds itself directly to you, creating an urgency and intimacy not found on other dark rides, as well as fostering in micro-narratives such that it doesn’t become a monotonous parade of special effects. This last point is perhaps most important, as it proves Sally to not just be gifted technical set designers, but also artisans of visual storytelling.

parade of special effects. This last point is perhaps most important, as it proves Sally to not just be gifted technical set designers, but also artisans of visual storytelling.

On my first ride (alone), I have my laser gun(s) ready as the vehicle silently enters the first scene. “All right, let’s fuck some minotaurs up! Hmm, I don’t see anything in this dark forest, a few toads croaking is all. No red shooter targets here. Wait a minute, I see something up ahead! Oh, it’s just the faun Pan playing a sad tune on his pipes. I wonder where the monsters are. Hold on, what’s that? A puppy trapped on a leash barking at me? That’s not anything, what’s he doing here? Seems out of place… Hmm, did it all of a sudden just get really quiet? I can’t see anything anymore, it’s too dark. What’s going on, I wonder– HOLY FUCKING SHIT, SCREAMING HYDRAS ARE FLYING AT ME EVERYWHERE!!!”

And so it goes. I honestly didn’t even try to score points after completing my first ride, partly because the laser response was crap anyway, but partly because I was just so wrapped up in this mythical world I didn’t want anything to distract me. My criticism of the unreality of themed attractions remains the same, that our appreciation of the experience is to some degree dependant on our willingness to accept what we see as being real, and aesthetic judgment is based on how well we are deceived. This is wrong. When King Lear staggers on stage carrying the dead body of his youngest daughter, one’s reaction has absolutely nothing to do with whether the audience can make believe that they’re not watching two actors on an empty, lit wooden stage, but because there is a profound emotional truth at the core of this image they are bearing witness to. The theme park industry (including on this ride) are still lightyears away from breaking those self-imposed boundaries that still contextualize every aesthetic judgment in terms of convincing authenticity; even at the point of 100% lifelikeness (which I might argue is impossible to achieve), that aesthetic barrier remains. But Labyrinth of the Minotaur took an important first step in the right direction, and Sally’s own Nights in White Satin took another. While the settings will always be fake, what won’t be is a sense of pacing, atmosphere, an original vision, a story… all tools the artist has to work with in pointing us closer to the realm of genuine aesthetic and emotional reality.

lit wooden stage, but because there is a profound emotional truth at the core of this image they are bearing witness to. The theme park industry (including on this ride) are still lightyears away from breaking those self-imposed boundaries that still contextualize every aesthetic judgment in terms of convincing authenticity; even at the point of 100% lifelikeness (which I might argue is impossible to achieve), that aesthetic barrier remains. But Labyrinth of the Minotaur took an important first step in the right direction, and Sally’s own Nights in White Satin took another. While the settings will always be fake, what won’t be is a sense of pacing, atmosphere, an original vision, a story… all tools the artist has to work with in pointing us closer to the realm of genuine aesthetic and emotional reality.

Comments