Michigan’s Adventure – Muskegon, Michigan

Most roller coasters adhere to an aesthetic of maximalism. It’s inherent in the advertised promise these structures make to their audiences. We want spectacle. We want an adrenaline rush. We want to have our sensory receptors screaming at the highest possible decibel. These are not qualities that lend themselves to understatement or restraint. A roller coaster is not a medium that suits itself to keeping the volume at a low, respectable level. We want our experience on a roller coaster to be big.

Recognizing this psychological desire, most parks and engineers treat the “thrill” produced by their roller coaster design as an economic resource to be maximized. Add more. Don’t stop. Waste nothing. Every element counts. Breathless pacing from start to finish. Each individual moment should produce as huge of an emotional impact as possible.

as an economic resource to be maximized. Add more. Don’t stop. Waste nothing. Every element counts. Breathless pacing from start to finish. Each individual moment should produce as huge of an emotional impact as possible.

Long ago it was enough to just build a coaster taller and faster, or make it do something unusual, like a vertical loop. Later, it was a question of how many loops. Enthusiasts clamored for more airtime; designers were happy to oblige. Rides grew bigger, longer, and loopier as a result, but it became clear that the designs still weren’t operating at maximal emotional efficiency. A coaster could always one-up the competition by adding more, but this usually happened at a 1:1 economic ratio which soon became prohibitively expensive. Around the turn of the millennium, a funny thing happened: trains and track gauges grew shorter and narrower, and footprints grew smaller, seemingly in contravention of the maximalist ethos. But this allowed layouts to become steeper, sharper, and twistier, packing in more thrills in per foot of track than before. Today’s ideal maximalist coaster is a lean yet mean scream machine.

prohibitively expensive. Around the turn of the millennium, a funny thing happened: trains and track gauges grew shorter and narrower, and footprints grew smaller, seemingly in contravention of the maximalist ethos. But this allowed layouts to become steeper, sharper, and twistier, packing in more thrills in per foot of track than before. Today’s ideal maximalist coaster is a lean yet mean scream machine.

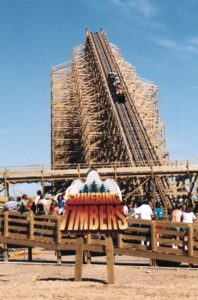

Shivering Timbers would appear to be a poster child for the maximalist aesthetic definition among coasters… at least as it had been defined circa 1998, when elements were still pretty big and traditional, and for a maximalist coaster it was mostly just a question of how many of these rather generic elements could be sequenced together before exhausting its kinetic energy. After all, why have just one airtime hill when you can have five? Despite the fact that other, newer coasters claim to offer more cumulative airtime during their layout, I don’t think any coaster has ever been designed before or since with such a single-minded focus on maximizing the total amount of weightlessness experienced during the course of its layout. Approaching Michigan’s Adventure for the first time from the south parking entrance, the structure can appear almost cartoonish for the way it stacks a seemingly endless series of tall camelback hills one after another, as if the property line is the only thing stopping it from attempting to circumnavigate the planet. Add more! Don’t stop! Waste nothing!

before exhausting its kinetic energy. After all, why have just one airtime hill when you can have five? Despite the fact that other, newer coasters claim to offer more cumulative airtime during their layout, I don’t think any coaster has ever been designed before or since with such a single-minded focus on maximizing the total amount of weightlessness experienced during the course of its layout. Approaching Michigan’s Adventure for the first time from the south parking entrance, the structure can appear almost cartoonish for the way it stacks a seemingly endless series of tall camelback hills one after another, as if the property line is the only thing stopping it from attempting to circumnavigate the planet. Add more! Don’t stop! Waste nothing!

I consider Shivering Timbers to be CCI’s greatest achievement and the best wooden roller coaster built during the 1990’s.1 This may sound somewhat strange, given that in the past I’ve been rather critical of the “airtime-maximization” mentality that at one time seemed prevalent among much of the enthusiast discourse surrounding rides. The aesthetic nuance of many great coasters is inevitably lost if your only evaluating criteria is to tally the number and length of airtime moments found throughout a ride layout (primarily judged from the back row), and the ride with the highest tally wins. Shivering Timbers could seem like perhaps the most blatant attempt at designing to this mentality, offering little variation in pacing or g-force between its fourteen airtime hills. As a coaster aesthete, we’re supposed to like things like variable pacing and unique element sequences and designs that show a spark of originality and creative ambition. Shivering Timbers has none of that, in favor of the same damn airtime hill copied and pasted over and over until whatever 1990’s engineering software used by CCI ran out of memory.

of many great coasters is inevitably lost if your only evaluating criteria is to tally the number and length of airtime moments found throughout a ride layout (primarily judged from the back row), and the ride with the highest tally wins. Shivering Timbers could seem like perhaps the most blatant attempt at designing to this mentality, offering little variation in pacing or g-force between its fourteen airtime hills. As a coaster aesthete, we’re supposed to like things like variable pacing and unique element sequences and designs that show a spark of originality and creative ambition. Shivering Timbers has none of that, in favor of the same damn airtime hill copied and pasted over and over until whatever 1990’s engineering software used by CCI ran out of memory.

Here’s the thing: despite all outward appearances, I don’t consider Shivering Timbers to belong to the maximalist aesthetic at all. In fact, quite the opposite. Shivering Timbers is a masterpiece in minimalism.

That’s right: Minimalism.

Okay, I know. A minimalist roller coaster sounds like a truly awful idea. It also sounds like an odd label for Shivering Timbers, a coaster with such an excess of airtime that could perhaps best be described as “absurdly hedonistic.” But let’s investigate what “minimalism” versus “maximalism” really mean as aesthetic criteria, especially in the context of a roller coaster design, and maybe my point will become clearer.

Minimalism, especially when applied to other arts, has a reputation for being either difficult and inaccessible, or subdued and slow-moving, if not both at the same time. If maximalism is about creating a grandiose, highly-emotional experience, then minimalism is about restraint and quietude. One goes big, the other goes small. Except that’s not really true. Neither minimalism nor maximalism is about the size of the final emotional payoff. Rather, it’s about the strategy used to get to that payoff. Minimalism and maximalism do not define the content of a work. A good minimalist experience can be profoundly thrilling, while a bad maximalist experience can be incredibly dull. In other arts, maximalism often has many gifted purveyors, but it’s also home to a lot of kitsch and bombast. And Michael Bay. Keep the volume cranked up to eleven, and sometimes you might feel more elated. But other times you might just go deaf. The same for minimalism. There’s lots of masters, and there’s lots of hacks. Sometimes it lands with a bone-rattling crescendo, other times with an ineffectual thud.

The key difference between minimalism and maximalism is one of range and identity. Minimalism is a way of creating something by selecting from a limited range of elements that constitute the whole work. Mix one color instead of three. Use two words instead of ten. Film one long master shot. Repeat elements. Make it uniform. Narrowly define the work’s identity. Maximalism, by contrast, is all about opening up that range as wide as possible. Paint more colors. Insert more adjectives. Edit lots of close-up shots in rapid succession. Add new elements you haven’t included yet. Make it diverse. Broaden the work’s identity until it encompasses everything.

The key difference between minimalism and maximalism is one of range and identity. Minimalism is a way of creating something by selecting from a limited range of elements that constitute the whole work. Mix one color instead of three. Use two words instead of ten. Film one long master shot. Repeat elements. Make it uniform. Narrowly define the work’s identity. Maximalism, by contrast, is all about opening up that range as wide as possible. Paint more colors. Insert more adjectives. Edit lots of close-up shots in rapid succession. Add new elements you haven’t included yet. Make it diverse. Broaden the work’s identity until it encompasses everything.

Yes, minimalism and maximalism occupy opposite ends of a spectrum. But it’s a spectrum that can sometimes circle back on itself, with the two extremes sharing more in common than with the “middle ground” in between. This is why Shivering Timbers can feel oddly both maximalist and minimalist at the same time. A purely maximalist version of Shivering Timbers would, I suspect, look a lot more like The Voyage. Although both share a similar footprint and element sequence, The Voyage is always introducing new variations on the central out-and-back theme. It might repeat certain elements, but never more than two or three times, and the choreography is constantly fluxing and evolving over the course of the ride time. That’s key to maximalism. In order for every element to feel as big as possible, it also has to feel different from everything that came before it, even if that difference is only by degrees and it still recycles the same basic ideas.2

back on itself, with the two extremes sharing more in common than with the “middle ground” in between. This is why Shivering Timbers can feel oddly both maximalist and minimalist at the same time. A purely maximalist version of Shivering Timbers would, I suspect, look a lot more like The Voyage. Although both share a similar footprint and element sequence, The Voyage is always introducing new variations on the central out-and-back theme. It might repeat certain elements, but never more than two or three times, and the choreography is constantly fluxing and evolving over the course of the ride time. That’s key to maximalism. In order for every element to feel as big as possible, it also has to feel different from everything that came before it, even if that difference is only by degrees and it still recycles the same basic ideas.2

Shivering Timbers doesn’t play that game. Although there is quite a bit of small variation between hill profiles if you look closely, the repetition tends to mask, rather than accentuate, any variation. As a result, the focus is less on the individual elements and more on the patterns that emerge across the entire sequence of elements. Although not as long or shrouded by trees as The Voyage, I often times feel “lost” within the layout on Shivering Timbers in a way that never happens on a maximalist ride where every element competes for my notice. Wait, is this the fourth camelback or the fifth? Are we more than halfway through the return course? Is this the last bunny hop before the helix, or are there still a couple more ahead? Where am I?

That’s minimalism at its best: create such a powerfully hypnotic pattern that you lose track of your relative position within space and time as measured against the work, and your internal state begins to synchronize and fully envelop within the rhythm of the external experience happening around you.

Shivering Timbers isn’t perfect in it’s dedication to minimalism. The double-up and trick-track in particular feel like places where the designers became nervous that they needed to do more, even if it breaks the pattern they spend so much time setting up. I don’t blame them. Minimalism can be scary to do if you don’t have complete confidence in what you’re doing. I wonder if Philip Glass ever worried that he might look stupid if he kept playing the same notes over and over again? I probably would. If the work fails, at least the maximalist artist or designer can always have the “hey, I tried my hardest” defense. Failed minimalism, on the other hand, can easily resemble a complete lack of effort or imagination. “You could have tried something else… anything else!”

Shivering Timbers isn’t perfect in it’s dedication to minimalism. The double-up and trick-track in particular feel like places where the designers became nervous that they needed to do more, even if it breaks the pattern they spend so much time setting up. I don’t blame them. Minimalism can be scary to do if you don’t have complete confidence in what you’re doing. I wonder if Philip Glass ever worried that he might look stupid if he kept playing the same notes over and over again? I probably would. If the work fails, at least the maximalist artist or designer can always have the “hey, I tried my hardest” defense. Failed minimalism, on the other hand, can easily resemble a complete lack of effort or imagination. “You could have tried something else… anything else!”

Fortunately, people can’t get enough of airtime, so in retrospect Shivering Timbers’ gamble that riders wouldn’t reject an endless series of airtime hills seems like a fairly safe one. Perhaps uncoincidentally, I haven’t seen a very successful minimalist ride that focuses on just lateral or positive forces; riders might quite literally be sick, bruised, or unconscious by the end of it. Airtime hills at least have the advantage that it must come in an undulating motion, making it a two-tone form of minimalism instead of a purely monotone form. That isn’t to say that minimalism doesn’t exist in other coasters. Some twister style coasters get close to achieving a minimalist style thanks to their endless staccato pacing of direction changes, but often they’re introducing too significant of variations on the formula to qualify as true minimalism. In fact,

Fortunately, people can’t get enough of airtime, so in retrospect Shivering Timbers’ gamble that riders wouldn’t reject an endless series of airtime hills seems like a fairly safe one. Perhaps uncoincidentally, I haven’t seen a very successful minimalist ride that focuses on just lateral or positive forces; riders might quite literally be sick, bruised, or unconscious by the end of it. Airtime hills at least have the advantage that it must come in an undulating motion, making it a two-tone form of minimalism instead of a purely monotone form. That isn’t to say that minimalism doesn’t exist in other coasters. Some twister style coasters get close to achieving a minimalist style thanks to their endless staccato pacing of direction changes, but often they’re introducing too significant of variations on the formula to qualify as true minimalism. In fact, if there’s one coaster that I consider the closest to Shivering Timbers’ minimalist ethos, it’s The Beast. Lacking the airtime of Shivering Timbers, The Beast is perhaps less immune to criticism from enthusiasts who are looking for more there there, although it’s no secret that I find these two rides to be about as good as it gets.

if there’s one coaster that I consider the closest to Shivering Timbers’ minimalist ethos, it’s The Beast. Lacking the airtime of Shivering Timbers, The Beast is perhaps less immune to criticism from enthusiasts who are looking for more there there, although it’s no secret that I find these two rides to be about as good as it gets.

The fact that the airtime is repeated so many times in a row means that you don’t have to worry as much about the ride throwing a curveball your way, or wondering when you need to brace for the next change in direction. After two or three repetitions, you can be more open and present for each moment of airtime. Your body adapts to the rhythm, which lessens cognitive focus on adjusting your body mechanics for different elements, and you become more fully attuned to the raw phenomenology of the experience. Like Sisyphus, after enough times the repetition begins to take on its own internal meaning. The ride doesn’t change that much from beginning to end, but we do. Other coasters throw so much different stuff at us that it’s hard for our minds to fully comprehend what’s happening, closing in and shutting off. For two-and-a-half minutes, Shivering Timbers gives us a chance to throw up our hands and fully live in its world. “One more time, with feeling.”

become more fully attuned to the raw phenomenology of the experience. Like Sisyphus, after enough times the repetition begins to take on its own internal meaning. The ride doesn’t change that much from beginning to end, but we do. Other coasters throw so much different stuff at us that it’s hard for our minds to fully comprehend what’s happening, closing in and shutting off. For two-and-a-half minutes, Shivering Timbers gives us a chance to throw up our hands and fully live in its world. “One more time, with feeling.”

Yet the real strength of Shivering Timbers’ minimalism is not in achieving a trance-like repetition of elements (something that I suspect requires multiple re-rides before the effect really sets in, and in truth really doesn’t set it apart that much from a typical flat ride), but rather comes in the way that it’s able to establish a dominant pattern of elements, only to suddenly contrast that experience with a completely different secondary pattern. The double helix at the end of Shivering Timbers is still one of the most powerful and effective I can think of on nearly any coaster (save perhaps for fellow minimalist The Beast), and it gets much of its power from its juxtaposition within the minimalist framework established by the rest of the ride.

a typical flat ride), but rather comes in the way that it’s able to establish a dominant pattern of elements, only to suddenly contrast that experience with a completely different secondary pattern. The double helix at the end of Shivering Timbers is still one of the most powerful and effective I can think of on nearly any coaster (save perhaps for fellow minimalist The Beast), and it gets much of its power from its juxtaposition within the minimalist framework established by the rest of the ride.

The helix itself is rather ordinary: consistently underbanked as is common in CCI designs, with a rather hard, sharp transition into the curve (which on a modern design would have been completely ironed out), and heavy, sustained laterals for the entire duration with relatively little dynamic fluctuation, save for a gentle increase in intensity halfway through as it transitions from the upper to lower level of the helix, picking up a bit of speed while bringing the support structure in closer. In this way the helix is very much in line with the rest of the minimalist character, just delivering plain and pure lateral forces for the extended finale. Even the simple far end turnaround is emotional elevated by this principle, putting a hard punctuation on the first act before experiencing the lull in the middle of the storm that separates it from the second act, and serves as a softer forewarning to what will ultimately become the grand finale.

entire duration with relatively little dynamic fluctuation, save for a gentle increase in intensity halfway through as it transitions from the upper to lower level of the helix, picking up a bit of speed while bringing the support structure in closer. In this way the helix is very much in line with the rest of the minimalist character, just delivering plain and pure lateral forces for the extended finale. Even the simple far end turnaround is emotional elevated by this principle, putting a hard punctuation on the first act before experiencing the lull in the middle of the storm that separates it from the second act, and serves as a softer forewarning to what will ultimately become the grand finale.

Humans are naturally pattern identifying creatures. When you establish a simple minimalist pattern, such as an endless wave of airtime hills, any abrupt variations after a long repetition will dramatically amplify the contrast between elements, creating more powerful emotional dynamics. This principle is central to the entire theory of element sequencing, which is dialectical in nature. The premise is that identity, especially of a subjective experience, can’t really be understood unless you place it in close context with its opposite identity. Light seems brighter after darkness. Loudness seems more intense after silence. Lateral G-forces feel more intense after floater airtime. This principle is an essential tool for artists, and a successful attraction can’t have just a single static identity, nor one that’s constantly in flux without ever staking a claim in one mode or another. You need sharp dialectical contrast.

wave of airtime hills, any abrupt variations after a long repetition will dramatically amplify the contrast between elements, creating more powerful emotional dynamics. This principle is central to the entire theory of element sequencing, which is dialectical in nature. The premise is that identity, especially of a subjective experience, can’t really be understood unless you place it in close context with its opposite identity. Light seems brighter after darkness. Loudness seems more intense after silence. Lateral G-forces feel more intense after floater airtime. This principle is an essential tool for artists, and a successful attraction can’t have just a single static identity, nor one that’s constantly in flux without ever staking a claim in one mode or another. You need sharp dialectical contrast.

Even after all these years, Shivering Timbers is still a landmark among coasters because no ride before or since has had such a singular, focused identity. Most coasters are designed by pulling from an entire bag of tricks, mixing different elements together and hoping that the right combination of the best elements will give them an edge over the competition. But with thousands of coasters operating worldwide (although tragically less than 200 of those remaining are wooden), perhaps it’s less important that our individual ride designs check off multiple boxes in pursuit of an abstract notion of “completeness”, and more important that each coaster have its own strongly defined identity. Shivering Timbers leaves no ambiguity as to what type of experience it is and is not, and whether after one ride or two hundred, your memory knows exactly how to categorize it. For as conceptually simple as the ride is, every element contributes to a cohesive experience, even if that means each element sacrifices its own individual ability to “stand out”. Shivering Timbers is pure in form, is unmistakable and unforgettable, and is a monolithic landmark among wooden roller coasters that has no peer.

Even after all these years, Shivering Timbers is still a landmark among coasters because no ride before or since has had such a singular, focused identity. Most coasters are designed by pulling from an entire bag of tricks, mixing different elements together and hoping that the right combination of the best elements will give them an edge over the competition. But with thousands of coasters operating worldwide (although tragically less than 200 of those remaining are wooden), perhaps it’s less important that our individual ride designs check off multiple boxes in pursuit of an abstract notion of “completeness”, and more important that each coaster have its own strongly defined identity. Shivering Timbers leaves no ambiguity as to what type of experience it is and is not, and whether after one ride or two hundred, your memory knows exactly how to categorize it. For as conceptually simple as the ride is, every element contributes to a cohesive experience, even if that means each element sacrifices its own individual ability to “stand out”. Shivering Timbers is pure in form, is unmistakable and unforgettable, and is a monolithic landmark among wooden roller coasters that has no peer.

Western Michigan is a land created by glaciers, which have left in their wake a landscape that’s neither flat and well-settled, nor rocky and mountainous, but a soft, sandy, sinuous young land. The ground is easily eroded by the winds that cruise in off the surrounding Great Lakes, which are large enough that they might be mistaken for the ocean if not for the freshwater and shallow, choppy waves. This shoreline is about as far west as you can go while still being in the Eastern time zone, and in combination with the northerly latitude means that the last rays of a summer sunset can sometimes linger in the sky until after 10:00pm, beckoning one to

Western Michigan is a land created by glaciers, which have left in their wake a landscape that’s neither flat and well-settled, nor rocky and mountainous, but a soft, sandy, sinuous young land. The ground is easily eroded by the winds that cruise in off the surrounding Great Lakes, which are large enough that they might be mistaken for the ocean if not for the freshwater and shallow, choppy waves. This shoreline is about as far west as you can go while still being in the Eastern time zone, and in combination with the northerly latitude means that the last rays of a summer sunset can sometimes linger in the sky until after 10:00pm, beckoning one to stay out late into the night. It’s sparsely populated, with its most successful inhabitants seeming to be the deer that thrive off the tall grasses and wildflowers that grow in the sandy soil between the otherwise repetitive pine forests. In a clearing in one of those forests atop a particularly flat part of the land, a Michigander decided to build a small deer park in the 1950’s, which later grew to include progressively larger amusements, until one day they were pouring the cement foundations into this land for what would become a world landmark of wooden roller coaster design.

stay out late into the night. It’s sparsely populated, with its most successful inhabitants seeming to be the deer that thrive off the tall grasses and wildflowers that grow in the sandy soil between the otherwise repetitive pine forests. In a clearing in one of those forests atop a particularly flat part of the land, a Michigander decided to build a small deer park in the 1950’s, which later grew to include progressively larger amusements, until one day they were pouring the cement foundations into this land for what would become a world landmark of wooden roller coaster design.

I remember being nine years old and seeing that wooden structure late in the summer of 1997, when there was only a crudely hand-painted sign proclaiming the arrival of Shivering Timbers, to become the nation’s third longest wooden roller coaster at over a mile long, and the towering frame of an incomplete 122 foot tall lift hill abruptly terminating before a massive blank canvas of an empty field, begging to be filled in with nearly unlimited possibilities.

I remember being nine years old and seeing that wooden structure late in the summer of 1997, when there was only a crudely hand-painted sign proclaiming the arrival of Shivering Timbers, to become the nation’s third longest wooden roller coaster at over a mile long, and the towering frame of an incomplete 122 foot tall lift hill abruptly terminating before a massive blank canvas of an empty field, begging to be filled in with nearly unlimited possibilities.

At the time there were no virtual renders or even hand-drawn concept art available for the new ride, so I was largely left to imagine the configuration it would take after that point, save for the ghost of a small bunny hill faintly tracing through the support structure below. I was a bit surprised the following year to discover that they went with such a skinny, stripped-down out-and-back layout that wasn’t anything like the sprawling wooden monsters that at the time defined the country’s other largest wooden coasters.

Since it opened in 1998, I’ve ridden Shivering Timbers 253 times, in every year until 2014 when I moved from Northern Michigan to Southern California. While it’s not my absolute all-time favorite roller coaster (but close), it is the one ride that I still regard as uniquely “mine”. I remember standing in line for it my very first time at ten years old, staring up at the mountain of timber with a mix of anticipation and uncertainty. This ride completely redefined my home state’s only amusement park, the place I was familiar and comfortable with, and I wasn’t sure if there was a risk I might not like it. But I needn’t have worried. After a few more rides, we thought it prudent to keep track of how many laps I had done, seeing as I was likely to ride it quite a bit more in the years to come and might wish to keep track.

favorite roller coaster (but close), it is the one ride that I still regard as uniquely “mine”. I remember standing in line for it my very first time at ten years old, staring up at the mountain of timber with a mix of anticipation and uncertainty. This ride completely redefined my home state’s only amusement park, the place I was familiar and comfortable with, and I wasn’t sure if there was a risk I might not like it. But I needn’t have worried. After a few more rides, we thought it prudent to keep track of how many laps I had done, seeing as I was likely to ride it quite a bit more in the years to come and might wish to keep track.

We quickly learned in that first season that for whatever reason the green train ran significantly faster than the blue train, so much so that by late afternoon a significant percent of day visitors in the station would also try to arrange themselves to get green, likely fueled by the operator’s own occasional quips over the microphone that one train really was a superior experience. It’s a quirk that probably hasn’t been in effect since the turn of the millennium, yet even today I still get a small boost of satisfaction when my train turns up green.

We quickly learned in that first season that for whatever reason the green train ran significantly faster than the blue train, so much so that by late afternoon a significant percent of day visitors in the station would also try to arrange themselves to get green, likely fueled by the operator’s own occasional quips over the microphone that one train really was a superior experience. It’s a quirk that probably hasn’t been in effect since the turn of the millennium, yet even today I still get a small boost of satisfaction when my train turns up green.

Nowadays both trains run about the same, which is to say, somewhat roughly and slowly, with a lot of energy lost near the end of the layout that it once used to have. There was a time when the train would exit the helix and positively crash into the brakes, overshooting several calipers. Now it just kind of skids to a gentle stop as soon as it hits the first brake. The initial two-thirds of the ride are still typically astounding, leading me on my first ride of each season to think it’s been restored to its original form, although by the final moments it’s clear that some of the vigor is still missing after all. Preventative maintenance, like so many other once-great wooden coasters, is partly to blame, and although there have been some earnest and significant attempts to fix problem areas, the result is a ride that’s more inconsistent than ever before. My ideal form of Shivering Timbers is the one that existed when Michigan’s Adventure was still an independent park prior to 2002, when the lawn in front of the coaster was all dirt and sand, a lion character represented the park, and the nearby Corkscrew was still a dirty all-white.

In those days Michigan’s Adventure was little more than a collection of carnival rides and cheap brick buildings atop a sandy, weedy clearing in the middle of a secondary-growth forest. It mostly still is that way, although more color has been added and the surrounding landscape has had an opportunity to grow in with reeds, wildflowers, and small pines, giving the park an ever-so-slightly more naturalistic, local flavor. Michigan’s Adventure was particularly hard-hit by criticisms of barrenness from enthusiasts shortly after Shivering Timbers’ opening, which wasn’t entirely fair since the area had been devastated by a windstorm the year before, and which have since had an opportunity to grow back. But it’s still

In those days Michigan’s Adventure was little more than a collection of carnival rides and cheap brick buildings atop a sandy, weedy clearing in the middle of a secondary-growth forest. It mostly still is that way, although more color has been added and the surrounding landscape has had an opportunity to grow in with reeds, wildflowers, and small pines, giving the park an ever-so-slightly more naturalistic, local flavor. Michigan’s Adventure was particularly hard-hit by criticisms of barrenness from enthusiasts shortly after Shivering Timbers’ opening, which wasn’t entirely fair since the area had been devastated by a windstorm the year before, and which have since had an opportunity to grow back. But it’s still a fairly barren park, one that, unlike many other regional parks built in the 60’s and 70’s, clearly never aspired to be anything more than a collection of rides on a flat parcel of land.

a fairly barren park, one that, unlike many other regional parks built in the 60’s and 70’s, clearly never aspired to be anything more than a collection of rides on a flat parcel of land.

While landscaping and painting has marginally improved, to this day there is still no live entertainment, no dark rides, no roller coasters manufactured after the 1990’s, and only one food-service location with indoor seating. Enthusiasts traveling long distances to Michigan’s Adventure may be disappointed with what they find after checking Shivering Timbers off their list. The park under Cedar Fair’s stewardship has prioritized keeping the price of admission below $30 in exchange for undertaking any large new capital expansion projects, which given the state of the regional economy and the proximity of Cedar Point as a better, more expensive alternative is perhaps understandable, if uninspiring.

economy and the proximity of Cedar Point as a better, more expensive alternative is perhaps understandable, if uninspiring.

This absolute de-emphasis on the components that we typically assume make a good park experience were overlooked by me until much later when I had more points of comparison. A visit to Michigan’s Adventure was about the rides, and in the absence of any themed storylines throughout the park, I created my own sense of narrative continuity upon these rides. Of course Shivering Timbers should finish with a double helix! How else could it end? I didn’t necessarily know why that was a fact. I just knew that every time I rode it that it felt right.

Even rides like Zach’s Zoomer, Corkscrew, Wolverine Wildcat, and Logger’s Run, no matter how short or simple they might appear, after enough repeat rides, would manifest a distinctive experiential arc that I could narrate my own adventures to. In the absence of grand gestures of spectacle and theme, I had to pay attention to the small details that gave each ride its own unique pleasures. Intuitively, there was a reason why Shivering Timbers was the king of the park, something about it that suggested there was more thought put into it than any other ride in the park, and it wasn’t just because it was bigger and longer and had more airtime than all the others. (Although that certainly helped.) I needed to find a way to describe what that feeling was.

wasn’t just because it was bigger and longer and had more airtime than all the others. (Although that certainly helped.) I needed to find a way to describe what that feeling was.

I sometimes wonder how much of an influence do the particular circumstances and situations we find ourselves in, especially in youth, have on shaping the way one thinks and sees the world? I can argue for a long time about the objective validity in certain aesthetic principles of theme parks and attractions (or even the fact that aesthetic principles should be applied and discussed for all attractions, even those that some might consider more vulgar expressions of the form), yet there’s no escaping the fact that there’s a particular subjective pathway we must walk (or ride) to reach those conclusions. Shivering Timbers is objectively one of the world’s best wooden roller coasters, and it is subjectively one of my all-time favorites.

for all attractions, even those that some might consider more vulgar expressions of the form), yet there’s no escaping the fact that there’s a particular subjective pathway we must walk (or ride) to reach those conclusions. Shivering Timbers is objectively one of the world’s best wooden roller coasters, and it is subjectively one of my all-time favorites.

Now my question is, where does one begin and the other end?

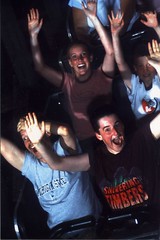

Shivering Timbers & I (2007)

Comments