The lasting appeal of the Disney brand can likely be ascribed in part to the origin myths that surround the company’s founding. Everyone knows “it was all started by a mouse”, and the dedication of Disneyland, “to all who come to this happy place, welcome,” is more entrenched in the cultural consciousness than a majority of inauguration speeches made by U.S. presidents. The lands found in the parks themselves are frequently origin stories, most notably Main Street U.S.A. in both Disneyland and The Magic Kingdom which mythologizes Walt’s adolescent roots as an American dreamer. Even after Walt, the EPCOT Center had a special creation myth as well, retold by fans about the original vision for an “Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow” and how it evolved into the Epcot we know today. These original parks in the Disney family are often considered timeless creations, whereas Disney’s Hollywood Studios (formerly Disney-MGM Studios before the licensing contract expired) would probably rather we forget the time of its creation altogether. Its origin story goes something like this:

When Universal Studios announced their plans to build a movie theme park in Orlando, Michael Eisner quickly scrambled together a press conference to announce his own plans for a third gate at Walt Disney World, which looked suspiciously identical to the proposed movie theme from their soon-to-be competitors. Using some ride concepts from unused proposals for their existing parks, Disney-MGM Studios managed to complete a year ahead of Universal Studios despite the later construction start, partly thanks to the Disney Company’s special jurisdiction in Florida that lets them issue their own construction permits. Upon opening their gates, visitors to Disney-MGM Studios were treated to a grand total of four different attractions to fill out their day of adventure, as well as a separate movie production studio which gave us such classics as Ernest Saves Christmas and Thunder in Paradise before it was eventually downsized back to California… not that that fact should be any reason they can’t still pretend that we get to watch real movies and television be made.

park in Orlando, Michael Eisner quickly scrambled together a press conference to announce his own plans for a third gate at Walt Disney World, which looked suspiciously identical to the proposed movie theme from their soon-to-be competitors. Using some ride concepts from unused proposals for their existing parks, Disney-MGM Studios managed to complete a year ahead of Universal Studios despite the later construction start, partly thanks to the Disney Company’s special jurisdiction in Florida that lets them issue their own construction permits. Upon opening their gates, visitors to Disney-MGM Studios were treated to a grand total of four different attractions to fill out their day of adventure, as well as a separate movie production studio which gave us such classics as Ernest Saves Christmas and Thunder in Paradise before it was eventually downsized back to California… not that that fact should be any reason they can’t still pretend that we get to watch real movies and television be made.

In retrospect the origins of today’s Disney’s Hollywood Studios probably seem a bit silly and misguided. Even given that it has higher annual attendance than Universal Studios by virtue of being part of the Disney World package, as the smallest of three (now four) gates the motivation for Disney’s Studios park to compete would never be as great as Universal’s focus of resources would be on their flagship property. The similarities and differences between the two parks today are telling. Both promised a peek behind the scenes of moviemaking even though both have ill-fated histories of actual movie production in Florida, and both have relatively uninspiring visual identities, simulating soundstages and movie sets that even if real wouldn’t have much innate aesthetic appeal anyway.1 Both parks also tend to be treated as the dumping grounds for intellectual properties their parent companies want to build a ride out of but wouldn’t quite fit behind their other more thematically structured gates.

as the smallest of three (now four) gates the motivation for Disney’s Studios park to compete would never be as great as Universal’s focus of resources would be on their flagship property. The similarities and differences between the two parks today are telling. Both promised a peek behind the scenes of moviemaking even though both have ill-fated histories of actual movie production in Florida, and both have relatively uninspiring visual identities, simulating soundstages and movie sets that even if real wouldn’t have much innate aesthetic appeal anyway.1 Both parks also tend to be treated as the dumping grounds for intellectual properties their parent companies want to build a ride out of but wouldn’t quite fit behind their other more thematically structured gates.

However, where Universal Studios Florida became big and muscular by adding major attractions on a frequent basis whether they fit the surrounding environment or not, Disney’s Hollywood Studios’ growth has been more conservative, with fewer total E-ticket attractions that also tend to be of more even quality, which has left many of the original themed environments still cohesively intact. There are more pathways and buildings around Hollywood Studios that are pleasurable to simply explore or admire the historical references at one’s own leisure (e.g. Sunset Blvd., Echo Lake), whereas Universal Studios emphasizes action with design choices intended to funnel us into the queue of the nearest attraction. Perpetually compared to the other three theme parks on Walt Disney World’s property, it can be easy to forget that if on its own Disney’s Hollywood Studios would still be a relatively beautiful park when inspected up close.

of more even quality, which has left many of the original themed environments still cohesively intact. There are more pathways and buildings around Hollywood Studios that are pleasurable to simply explore or admire the historical references at one’s own leisure (e.g. Sunset Blvd., Echo Lake), whereas Universal Studios emphasizes action with design choices intended to funnel us into the queue of the nearest attraction. Perpetually compared to the other three theme parks on Walt Disney World’s property, it can be easy to forget that if on its own Disney’s Hollywood Studios would still be a relatively beautiful park when inspected up close.

The fact is easily forgotten because, stepping back from each example of the wonderful attention to detail and examining the park grounds as a whole, Disney’s Hollywood Studios has a fairly monotonous aesthetic identity, roughly divided into two sprawling sections: the Golden Age Tinseltown look in the northern half and the studio soundstage look on the south side, with a few lone areas of IP-based attractions adding discontinuous lumps to the mix. While the other Walt Disney World parks use their environments to evoke universal stories of reassurance, wonder, or nature, Hollywood Studios by contrast is both narrow in concept and narcissistic in delivery. It’s a vanity project designed primarily to please the old guard of Hollywood executives who built it in the first place. A place to reminisce over how easy it used to be to deceive audiences with either a little glitz and glamour on the red carpet or some make-up and special effects on the silver screen, while assuming that modern audiences still share that same nostalgic desire to be duped by these manufactured illusions of the culture industry.2 The phrase “you ought to be in pictures” is glimpsed several times to remind us that the ability to make it into Hollywood should still be considered the highest endorsement of an individual’s beauty and self-worth, even if most people today would interpret such a sentiment as cutely quaint rather than truly honorary. Therefore it’s perhaps of interest to note that two of the most original attractions, The Twilight Zone Tower of Terror and Muppet*Vision 3D, are both to some degree deconstructions of the vainglorious attitudes towards movie magic that define the rest of this theme park.

by contrast is both narrow in concept and narcissistic in delivery. It’s a vanity project designed primarily to please the old guard of Hollywood executives who built it in the first place. A place to reminisce over how easy it used to be to deceive audiences with either a little glitz and glamour on the red carpet or some make-up and special effects on the silver screen, while assuming that modern audiences still share that same nostalgic desire to be duped by these manufactured illusions of the culture industry.2 The phrase “you ought to be in pictures” is glimpsed several times to remind us that the ability to make it into Hollywood should still be considered the highest endorsement of an individual’s beauty and self-worth, even if most people today would interpret such a sentiment as cutely quaint rather than truly honorary. Therefore it’s perhaps of interest to note that two of the most original attractions, The Twilight Zone Tower of Terror and Muppet*Vision 3D, are both to some degree deconstructions of the vainglorious attitudes towards movie magic that define the rest of this theme park.

All told Disney’s Hollywood Studios is still a worthwhile entry amongst Central Florida’s theme park selection, if not only because it has a collection of attractions with greater appeal to most ride enthusiasts than the average Disney park. Perhaps what it needs more than anything else could be as simple as a proper central icon instead of the Sorcerer’s Hat placed there “temporarily” since 2001. Something that could give the complete park a more unified, universal message, instead of a slapdash icon reminding us of the park’s slapdash heritage built by competing corporate egos with evidently very little imagination left in the world.

All told Disney’s Hollywood Studios is still a worthwhile entry amongst Central Florida’s theme park selection, if not only because it has a collection of attractions with greater appeal to most ride enthusiasts than the average Disney park. Perhaps what it needs more than anything else could be as simple as a proper central icon instead of the Sorcerer’s Hat placed there “temporarily” since 2001. Something that could give the complete park a more unified, universal message, instead of a slapdash icon reminding us of the park’s slapdash heritage built by competing corporate egos with evidently very little imagination left in the world.

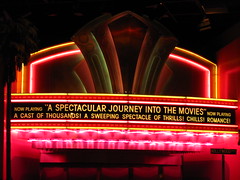

The Great Movie Ride

Here’s a dark ride built by geeks for geeks. At first the uninspired descriptive title and central placement as Hollywood Studio’s “mascot” attraction (à la Cinderella Castle or Spaceship Earth, this time with Mann’s Chinese Theatre) made me fear this could be a very vanilla work of Hollywood pageantry, overproduced as only Disney knows how. Thankfully that’s not (entirely) the case, as the show producers seem to demonstrate a genuine giddy enthusiasm for toying with many conventions of theme park attractions while simultaneously flattering our pop-culture savvy. Like, “wouldn’t-it-be-cool-if-the-ride-host-gets-kidnapped-by-a-villain-from-a-gangster-flick-or-spaghetti-western”, and “wouldn’t-it-be-cooler-if-then-the-gangster-gets-owned-by-the-xenomorph-from-Alien”, but then “wouldn’t-it-be-coolest-if-he-gets-his-

Here’s a dark ride built by geeks for geeks. At first the uninspired descriptive title and central placement as Hollywood Studio’s “mascot” attraction (à la Cinderella Castle or Spaceship Earth, this time with Mann’s Chinese Theatre) made me fear this could be a very vanilla work of Hollywood pageantry, overproduced as only Disney knows how. Thankfully that’s not (entirely) the case, as the show producers seem to demonstrate a genuine giddy enthusiasm for toying with many conventions of theme park attractions while simultaneously flattering our pop-culture savvy. Like, “wouldn’t-it-be-cool-if-the-ride-host-gets-kidnapped-by-a-villain-from-a-gangster-flick-or-spaghetti-western”, and “wouldn’t-it-be-cooler-if-then-the-gangster-gets-owned-by-the-xenomorph-from-Alien”, but then “wouldn’t-it-be-coolest-if-he-gets-his- face-melted-like-the-guy-in-Indiana-Jones-and-the-guardian-of-the-Ark-of-the-Covenant-turns-out-is-the-original-ride-host-in-disguise”? (Deep breath.) Given how many different ideas the Imagineers tried to cram together The Great Movie Ride easily could have suffered from over complication, but… well, okay, it is a little over complicated. Sure that’s part of the charm, but mixing live performers with audio-animatronics on the same stage almost always produces extra awkward results, and the script’s handful of “spontaneous surprises” often play stale or forced, simply due to the nature of a theme park attraction that requires casts members to read the same lines every twenty minutes every day for the rest of their career. The Great Movie Ride wants us to admire its cleverness and craftsmanship, but it’s mostly just an expensive work of fan fiction; an emotional parasite

face-melted-like-the-guy-in-Indiana-Jones-and-the-guardian-of-the-Ark-of-the-Covenant-turns-out-is-the-original-ride-host-in-disguise”? (Deep breath.) Given how many different ideas the Imagineers tried to cram together The Great Movie Ride easily could have suffered from over complication, but… well, okay, it is a little over complicated. Sure that’s part of the charm, but mixing live performers with audio-animatronics on the same stage almost always produces extra awkward results, and the script’s handful of “spontaneous surprises” often play stale or forced, simply due to the nature of a theme park attraction that requires casts members to read the same lines every twenty minutes every day for the rest of their career. The Great Movie Ride wants us to admire its cleverness and craftsmanship, but it’s mostly just an expensive work of fan fiction; an emotional parasite that survives by feeding off superior works of art. Sure the satisfaction of winning a game of “Spot the Movie References” can be real, it’s just also not very deep.

that survives by feeding off superior works of art. Sure the satisfaction of winning a game of “Spot the Movie References” can be real, it’s just also not very deep.

Grade: C+

Indiana Jones Epic Stunt Spectacular!

Of course everything at a Disney park is fake, but sometimes the fakery is directly acknowledged while (most) other times our disbelief is supposed to be suspended indefinitely. There’s an extended bit where one of the group of audience members they bring on stage is actually a plant, which our initial ignorance of the confederate’s presence allows for some amusing did-that-really-just-happen gags. When the set culminates in an outrageous stunt that instantly clues everyone into the act, the show wisely doesn’t try to stretch our disbelief any further and immediately acknowledges the ruse so that everyone can authentically cheer a fine performance (one most didn’t even realize was a performance twenty seconds earlier). Well played, and enjoyable entertainment. Given that the majority of the Indiana Jones Epic Stunt Spectacular doesn’t try to be a work of theater but just an honest demonstration of the physical stunts and special effects that make movie magic, it’s therefore more conspicuously odd when the show writers do try to enforce an obviously fictional conceit. The worst offender is the repeated claims to convince us this set is actually used

of the confederate’s presence allows for some amusing did-that-really-just-happen gags. When the set culminates in an outrageous stunt that instantly clues everyone into the act, the show wisely doesn’t try to stretch our disbelief any further and immediately acknowledges the ruse so that everyone can authentically cheer a fine performance (one most didn’t even realize was a performance twenty seconds earlier). Well played, and enjoyable entertainment. Given that the majority of the Indiana Jones Epic Stunt Spectacular doesn’t try to be a work of theater but just an honest demonstration of the physical stunts and special effects that make movie magic, it’s therefore more conspicuously odd when the show writers do try to enforce an obviously fictional conceit. The worst offender is the repeated claims to convince us this set is actually used for filming movies, as if studio films are produced with live studio audiences and being a Harrison Ford stunt double for the Indiana Jones franchise is a steady career with regular 9-5 working hours, ideal for the muscular 20-something theater grads they’ve hired. Maybe this premise worked for one year in 1989 when this show first debuted and the Last Crusade opened in theaters featuring a still youthful Mr. Ford, but today it’s just a distracting reminder of how Disney can’t be bothered to update even a few lines of script for a live performance in over twenty years. It also suggests the writers don’t have confidence to let their show stand on its own merits; don’t worry, no one will be disappointed to learn that your theme park stunt show isn’t real and is really only there to entertain audiences in a theme park with stunts.

for filming movies, as if studio films are produced with live studio audiences and being a Harrison Ford stunt double for the Indiana Jones franchise is a steady career with regular 9-5 working hours, ideal for the muscular 20-something theater grads they’ve hired. Maybe this premise worked for one year in 1989 when this show first debuted and the Last Crusade opened in theaters featuring a still youthful Mr. Ford, but today it’s just a distracting reminder of how Disney can’t be bothered to update even a few lines of script for a live performance in over twenty years. It also suggests the writers don’t have confidence to let their show stand on its own merits; don’t worry, no one will be disappointed to learn that your theme park stunt show isn’t real and is really only there to entertain audiences in a theme park with stunts.

Grade: C-

Star Tours – The Adventures Continue

Some people can’t do roller coasters, while others get queasy on spinning flat rides. I’ll be honest: my Achilles’ heel seems to be motion simulator rides. Sure I can ride them, but sitting in a claustrophobic bouncing box in front of the dim flicker of a 3D movie screen while concentrating my eyes on an artificial focal length, it doesn’t take long before the back of my retinas start to strain and the bottom of my stomach begins to tighten. Surprisingly, I find neither sensation to be particularly enjoyable. Thus the revamped Star Tours, which touts an impressive 54 different film sequences for a new adventure each time, could easily become something of a curse for a completionist prone to motion sickness such as myself. Still, with the aid of Dramamine and FastPasses I managed a total of four rides before having to call it quits, and that was more because of my annoyance that my fourth ride consisted of segments I had already seen at least twice while a handful of possible scenes continued to elude me. As an experiential short film set in the Star Wars universe there’s no doubt that Star Tours is tremendously successful at what it does, and the randomized sequences to encourage multiple re-rides is a long overdue idea to extract more value for repeat visitors at a lower marginal expense to the designers,3 even though there’s really only three

revamped Star Tours, which touts an impressive 54 different film sequences for a new adventure each time, could easily become something of a curse for a completionist prone to motion sickness such as myself. Still, with the aid of Dramamine and FastPasses I managed a total of four rides before having to call it quits, and that was more because of my annoyance that my fourth ride consisted of segments I had already seen at least twice while a handful of possible scenes continued to elude me. As an experiential short film set in the Star Wars universe there’s no doubt that Star Tours is tremendously successful at what it does, and the randomized sequences to encourage multiple re-rides is a long overdue idea to extract more value for repeat visitors at a lower marginal expense to the designers,3 even though there’s really only three different sequences of significance that can be randomly rearranged in four spots like a Twist-and-Match toy figurine. For anyone who hasn’t already sworn allegiance to the Rebel Alliance before boarding their StarSpeeder, they may find that this lottery ball approach to storytelling shares a lot of the same narrative deficiencies as any other “Choose Your Own Adventure” story… and here you don’t even have the freedom to choose. Instead of 54 equally interchangeable riffs on the same concept, wouldn’t we have been better off choosing between three complete and completely different story arcs?

different sequences of significance that can be randomly rearranged in four spots like a Twist-and-Match toy figurine. For anyone who hasn’t already sworn allegiance to the Rebel Alliance before boarding their StarSpeeder, they may find that this lottery ball approach to storytelling shares a lot of the same narrative deficiencies as any other “Choose Your Own Adventure” story… and here you don’t even have the freedom to choose. Instead of 54 equally interchangeable riffs on the same concept, wouldn’t we have been better off choosing between three complete and completely different story arcs?

Grade: C

3D/4D movie attractions usually rank below average on the theme park attraction totem pole, but I must make an exception in this case. Here is what separates Muppet*Vision 3D from the rest: Love. Jim Henson and company took the time to write a genuinely clever script full of their typically absurdist humor, which would sadly become Henson’s last time voicing Kermit the Frog before his death in 1990. Nothing is safe from the anarchy of the Muppets, who this time set a lock on both theme parks and movie production as a primary subject of their merciless slapstick, which lends the film some deliciously contextual satiric relevance. Targets include the cheap gimmicks 3D movies typically employ to elicit an audience reaction by reaching through the screen for no reason related to the story; the artificiality of “lifelike” audio-animatronics who are in fact bolted in place and thus can never, ahem, relieve themselves between shows; and most hilariously, a parody/veiled critique of Epcot’s World Showcase in the form of Sam the Eagle’s patriotic final act titled “A Salute to All Nations, But Mostly America”. While sometimes the manic energy starts to run around in circles with no objective in sight, the only real downside of Muppet*Vision 3D that would cause hesitation over a second viewing is an interminable preshow that keeps everyone on their feet for much longer than seems necessary. Otherwise this is possibly the best 3D movie attraction currently playing at a major theme park.

an audience reaction by reaching through the screen for no reason related to the story; the artificiality of “lifelike” audio-animatronics who are in fact bolted in place and thus can never, ahem, relieve themselves between shows; and most hilariously, a parody/veiled critique of Epcot’s World Showcase in the form of Sam the Eagle’s patriotic final act titled “A Salute to All Nations, But Mostly America”. While sometimes the manic energy starts to run around in circles with no objective in sight, the only real downside of Muppet*Vision 3D that would cause hesitation over a second viewing is an interminable preshow that keeps everyone on their feet for much longer than seems necessary. Otherwise this is possibly the best 3D movie attraction currently playing at a major theme park.

Studio Backlot Tour

This was closed for refurbishment at the time of my visit. I missed out on the Studio Tour at the sister park in Paris for the same reason, and having done all but one of the Universal parks, the one I’m still missing would also be the only one that has a studio tour. One of these days I’ll finally get to sit on a tram and be shuttled between movie sets accompanied by the cadence of a chirpy tour guide, but that day would not be today. That’s more time for Tower rides, then.

With Toy Story Midway Mania the interactive shooter dark ride format has reached its apogee. Never again in the future of mankind will a dark ride equipped with a plastic wank gun be as gleefully fun as this ride is. Hooray. Now that we won’t need any more attractions that combine beloved children’s characters with the central mechanic from the “Deer Hunter” videogame series, can we please go back to making dark rides where the focus is on things like story and atmosphere and other arty crap? Between the HD-3D video screens that immerse you in the game like it’s the world’s largest iPad; the real-time projectile rings, darts, and balls that ricochet off scenery with supreme anarchic satisfaction; or the way vehicles suddenly yank and spin you from one level to the next imbuing the game with a physical sense of urgency… it’s impossible to make this formula more entertaining without controlled substances. And I’m not being (completely) sarcastic. Ride it once for what will seem like the second-best four minutes of your life so you’ll never have to bother again. Beware, the line fills up fast, so get a FastPass early in the day and do it quick before Mr. Potato Head has another aneurysm.

or the way vehicles suddenly yank and spin you from one level to the next imbuing the game with a physical sense of urgency… it’s impossible to make this formula more entertaining without controlled substances. And I’m not being (completely) sarcastic. Ride it once for what will seem like the second-best four minutes of your life so you’ll never have to bother again. Beware, the line fills up fast, so get a FastPass early in the day and do it quick before Mr. Potato Head has another aneurysm.

Grade: C

The Magic of Disney Animation

This indoor complex houses several different attractions, including a show about animated character development, costumed character meet-and-greets (there are always meet-and-greets at Disney parks, and they often command some of the longest lines), interactive games, and a museum of Disney animation artwork. The combination live/projected show actually does offer some worthwhile insights into Disney’s creative process, even if the show writers seemed to lack confidence over the audience’s sustained interest in this material by overstuffing the script with throwaway gags. The interactive activities on the main floor are fairly unremarkable, not helped by the recent proliferation of the App marketplace that now makes large computer kiosks housing mini-games such as these almost entirely redundant.

This indoor complex houses several different attractions, including a show about animated character development, costumed character meet-and-greets (there are always meet-and-greets at Disney parks, and they often command some of the longest lines), interactive games, and a museum of Disney animation artwork. The combination live/projected show actually does offer some worthwhile insights into Disney’s creative process, even if the show writers seemed to lack confidence over the audience’s sustained interest in this material by overstuffing the script with throwaway gags. The interactive activities on the main floor are fairly unremarkable, not helped by the recent proliferation of the App marketplace that now makes large computer kiosks housing mini-games such as these almost entirely redundant. It’s cute that a program script can determine after six short questions that if I were a Disney character I would be Jafar from Aladdin (I couldn’t disagree), but in this decade do I really still need to travel to Florida for that information? The adjoining museum about Disney animation is perhaps the most worthwhile, even if (and perhaps this is simply due to the nature of animation) the exhibits are very two-dimensional and the experience is akin to a coffee table book you have to read while standing. Nevertheless I walked away with some newfound appreciation for the artwork in a number of classic and recent animated films I hadn’t previously given as much consideration to, which seems like a solid signal that this gallery must be a success.4

It’s cute that a program script can determine after six short questions that if I were a Disney character I would be Jafar from Aladdin (I couldn’t disagree), but in this decade do I really still need to travel to Florida for that information? The adjoining museum about Disney animation is perhaps the most worthwhile, even if (and perhaps this is simply due to the nature of animation) the exhibits are very two-dimensional and the experience is akin to a coffee table book you have to read while standing. Nevertheless I walked away with some newfound appreciation for the artwork in a number of classic and recent animated films I hadn’t previously given as much consideration to, which seems like a solid signal that this gallery must be a success.4

The Twilight Zone Tower of Terror

Tower of Terror could make the best argument of any Disney ride that a theme park attraction could be considered as a uniquely singular category of artistic storytelling. It’s not that there aren’t better or more artistically competent Disney attractions (although the list is very short), but it is the only one that makes the exclusive experiential capability of thrill ride hardware and environmental immersion an absolutely essential component to the articulation of a detailed narrative. As great – in fact, greater – as the similarly weird and wonderful Haunted Mansion is, the slow-moving vehicles gliding gently past a fixed series of scenes could be translated into a different visual story medium without significant compromise, whereas a plot in which the audience must personally experience a zero-gravity freefall down an elevator shaft could not be replicated anywhere outside the theme park medium.5 The story, culled from an episode of the Twilight Zone, offers a breathtaking impression of Hollywood’s Golden Age as a source of simultaneous beauty and moral decay, cursed by the specter of time as familiar objects (including our own faces) phase in and out of the stardust from whence we came. In no other work of fiction has the existential dread rising from the pit of our stomach been felt so literally.

vehicles gliding gently past a fixed series of scenes could be translated into a different visual story medium without significant compromise, whereas a plot in which the audience must personally experience a zero-gravity freefall down an elevator shaft could not be replicated anywhere outside the theme park medium.5 The story, culled from an episode of the Twilight Zone, offers a breathtaking impression of Hollywood’s Golden Age as a source of simultaneous beauty and moral decay, cursed by the specter of time as familiar objects (including our own faces) phase in and out of the stardust from whence we came. In no other work of fiction has the existential dread rising from the pit of our stomach been felt so literally.

Yet while Tower of Terror could make the strongest argument for the story-ride fusion as a unique artistic medium, I’m frustrated by certain aspects that weaken this position. There are hints of intriguing ideas that could form the bedrock of a great popular science fiction story; e.g. Hollywood’s downfall reinterpreted as a modern Icarus myth featuring an iconic tower that reached for the sun only to fall when it got too close, or the notion that the familiar world is an illusory construct of ancient metaphysical entities. However there’s also a sense that any deeper interpretations are mere thematic ghosts left behind from the television show, and discussion over the story’s meaning would be more relevant to the source material than the watered-down remix in the attraction. Most of the narrative details are isolated to the corner of a dark room where a sixteen inch television screen6 quickly answers

argument for the story-ride fusion as a unique artistic medium, I’m frustrated by certain aspects that weaken this position. There are hints of intriguing ideas that could form the bedrock of a great popular science fiction story; e.g. Hollywood’s downfall reinterpreted as a modern Icarus myth featuring an iconic tower that reached for the sun only to fall when it got too close, or the notion that the familiar world is an illusory construct of ancient metaphysical entities. However there’s also a sense that any deeper interpretations are mere thematic ghosts left behind from the television show, and discussion over the story’s meaning would be more relevant to the source material than the watered-down remix in the attraction. Most of the narrative details are isolated to the corner of a dark room where a sixteen inch television screen6 quickly answers the perfunctory Who-What-Where-When bullet points from the storyteller’s manual while leaving the more interesting questions of How and Why largely unanswered. Perhaps this could be seen as a minimalist approach to story intended to foster suspense and encourage visitors to reach their own conclusions, but more realistically this brief and overly-expository video suggests that engagement with such questions was never intended in the first place. As long as the preshow provides adequate justification for the falling elevator concept and finishes with an eerie feeling of mystery, it matters not if the story has any deeper independent meaning. In this case “story” or “theme” becomes a means to an end: it’s window dressing there for those who would admire it the same way as they will distantly admire the set design or special effects,

the perfunctory Who-What-Where-When bullet points from the storyteller’s manual while leaving the more interesting questions of How and Why largely unanswered. Perhaps this could be seen as a minimalist approach to story intended to foster suspense and encourage visitors to reach their own conclusions, but more realistically this brief and overly-expository video suggests that engagement with such questions was never intended in the first place. As long as the preshow provides adequate justification for the falling elevator concept and finishes with an eerie feeling of mystery, it matters not if the story has any deeper independent meaning. In this case “story” or “theme” becomes a means to an end: it’s window dressing there for those who would admire it the same way as they will distantly admire the set design or special effects, and for everyone else it’s an excuse to put a drop tower ride in a Disney park. Given that the majority of people will exit chattering excitedly over what the ride did rather than what the ride was about, I can’t help but feel that for all Tower of Terror does right, the formula to make theme park attractions a “story-first” medium has yet to find the perfect balance.

and for everyone else it’s an excuse to put a drop tower ride in a Disney park. Given that the majority of people will exit chattering excitedly over what the ride did rather than what the ride was about, I can’t help but feel that for all Tower of Terror does right, the formula to make theme park attractions a “story-first” medium has yet to find the perfect balance.

Grade: B+

Rock ‘n’ Roller Coaster

Okay Disney, we get it: you can be just as much of a badass as Universal Studios. The regrettably short-lived Hard Rock Park still beat both of your attempts at rock idolatry, as that property was created by people who evidenced a true love for the music unlike these poseurs sitting at the cool kid’s table in central Florida. So, Rock ‘n’ Roller Coaster is actually a pretty good Disney attraction while simultaneously being a pretty mediocre roller coaster.7 The show portion of the attraction (i.e. everything built by Imagineers) is simultaneously very “counter-Disney” while also extremely “classic Disney”, and I respect the balancing act needed to make this original concept (at the time) work. The visual aesthetic, which transitions from an ultra-modernist recording studio (the attraction’s “cover art”, as it were) to a dark and grungy backstage area

Okay Disney, we get it: you can be just as much of a badass as Universal Studios. The regrettably short-lived Hard Rock Park still beat both of your attempts at rock idolatry, as that property was created by people who evidenced a true love for the music unlike these poseurs sitting at the cool kid’s table in central Florida. So, Rock ‘n’ Roller Coaster is actually a pretty good Disney attraction while simultaneously being a pretty mediocre roller coaster.7 The show portion of the attraction (i.e. everything built by Imagineers) is simultaneously very “counter-Disney” while also extremely “classic Disney”, and I respect the balancing act needed to make this original concept (at the time) work. The visual aesthetic, which transitions from an ultra-modernist recording studio (the attraction’s “cover art”, as it were) to a dark and grungy backstage area (where the heart of rock ‘n’ roll is found), are both quite different from anything else found on Walt Disney World property with its traditional focus on reassuring fantasies and nostalgia. Yet the Rock ‘n’ Roller Coaster is hardly antiestablishment, as most of the traditions of Disney design are still present underneath it all; from the series of enchanted portals that gradually take us someplace removed from the everyday, to the abundant nostalgia that comforts us like a friendly hug… only this time for a generation that cherishes memorabilia from The Doors or Jimi Hendrix Experience rather than the typical 1950’s cultural iconography of other Disney parks. Unfortunately the coaster portion of the attraction (i.e. everything built by Vekoma) is also pretty last generational as well. Predictably there’s no sense of how to pace a layout so it’s exciting

(where the heart of rock ‘n’ roll is found), are both quite different from anything else found on Walt Disney World property with its traditional focus on reassuring fantasies and nostalgia. Yet the Rock ‘n’ Roller Coaster is hardly antiestablishment, as most of the traditions of Disney design are still present underneath it all; from the series of enchanted portals that gradually take us someplace removed from the everyday, to the abundant nostalgia that comforts us like a friendly hug… only this time for a generation that cherishes memorabilia from The Doors or Jimi Hendrix Experience rather than the typical 1950’s cultural iconography of other Disney parks. Unfortunately the coaster portion of the attraction (i.e. everything built by Vekoma) is also pretty last generational as well. Predictably there’s no sense of how to pace a layout so it’s exciting to the very end. The launch is cool (the use of lighting makes it look much faster than it really is, about twice as strong as a commercial airliner takeoff) and it immediately pours into the signature double rollover maneuver. After that the bulky limo-train lumbers around a series of flat geometric curves and block brakes with a lone corkscrew making a cameo appearance at some arbitrary midpoint. Basically a rip-off of the Premier-built Flight of Fear coasters that opened three years prior, lacking are the nimble directional changes, strategic lulls and crescendos, and final corkscrew that forcefully informs you of the finish. Of course the coaster component isn’t all that matters, but given that Disney thought it mattered enough to break the diegetic construct and put “Roller Coaster” in the very title, I don’t feel out of line asking for better.

to the very end. The launch is cool (the use of lighting makes it look much faster than it really is, about twice as strong as a commercial airliner takeoff) and it immediately pours into the signature double rollover maneuver. After that the bulky limo-train lumbers around a series of flat geometric curves and block brakes with a lone corkscrew making a cameo appearance at some arbitrary midpoint. Basically a rip-off of the Premier-built Flight of Fear coasters that opened three years prior, lacking are the nimble directional changes, strategic lulls and crescendos, and final corkscrew that forcefully informs you of the finish. Of course the coaster component isn’t all that matters, but given that Disney thought it mattered enough to break the diegetic construct and put “Roller Coaster” in the very title, I don’t feel out of line asking for better.

Grade: C+

Summary

A typical product of Hollywood’s most self-congratulatory impulses, some high-grade attractions save Disney’s Hollywood Studios from obsolescence in the competitive Orlando market.

Overall Grade: C

Comments