Ripon, Yorkshire, England, UK – Wednesday, June 16th, 2010

I would see the Pope. I would walk along the canals of Venice. Look down upon the city of Paris in an early morning fog. Dangle over the cliffs of Mohar in western Ireland. I would see masterpieces by Michelangelo, Picasso, and Goya. I would stand ten yards from Roger Federer at Wimbledon. Among the roller coasters I would visit include Nemesis, Expedition GeForce, Blue Fire, iSpeed, Dragon Khan, Megafobia, and countless others.

I am not in any way exaggerating when I tell you that, if asked what single thing I most was anticipating from my five and a half months in eleven countries in Europe, my reply would be “my first ride on the Ultimate at Lightwater Valley”. It would also not be beyond hyperbole to state that I was partly justified for my anticipation.

It would also not be beyond hyperbole to state that I was partly justified for my anticipation.

To place this claim in perspective, as longtime readers may know the Beast remains one of my eccentric beloveds in the roller coaster realm, and being the ride that dethroned the Beast’s record for length the Ultimate is perhaps the only other ride in the world that draws comparison. However, of more importance to me was the fact that I’d be undertaking my first ride on the Ultimate with almost no clue what the layout would be like. Normally whenever I go to a park I research the hell out of the place and am already intimately familiar with the configurations such that I feel like I’ve already been on a coaster before I’ve even ridden it. Yet somehow I managed to evade all knowledge of what the Ultimate would do after cresting its first hill (except for that a second lift hill took place along the back half of the course), everything in between remained in the realm of my imagination. At first this ignorance was by accident, but later it came by deliberate choice. I am only granted the joy of ‘discovering’ a roller coaster for the first time once, and extremely rare is it to be while I’m actually on the rails authentically experiencing the psychological surprise its progression structure offers. That ignorance was an incredibly valuable thing and I had to work hard to defend it as I came ever closer to making my sojourn to Lightwater Valley a reality. In fact, after publishing my article on the Beast I received more than one written reply that included a detailed description of the Ultimate which I had to instantly avert my eyes from. (Just a warning to anyone who wishes to do the same for their first ride on the Ultimate, I will be revealing many details in the following paragraphs for those who are curious.)

like I’ve already been on a coaster before I’ve even ridden it. Yet somehow I managed to evade all knowledge of what the Ultimate would do after cresting its first hill (except for that a second lift hill took place along the back half of the course), everything in between remained in the realm of my imagination. At first this ignorance was by accident, but later it came by deliberate choice. I am only granted the joy of ‘discovering’ a roller coaster for the first time once, and extremely rare is it to be while I’m actually on the rails authentically experiencing the psychological surprise its progression structure offers. That ignorance was an incredibly valuable thing and I had to work hard to defend it as I came ever closer to making my sojourn to Lightwater Valley a reality. In fact, after publishing my article on the Beast I received more than one written reply that included a detailed description of the Ultimate which I had to instantly avert my eyes from. (Just a warning to anyone who wishes to do the same for their first ride on the Ultimate, I will be revealing many details in the following paragraphs for those who are curious.)

This was all back when I assumed the Ultimate was nothing particularly great in the first place. It was the longest ride in the world (formerly in length before the Steel Dragon 2000 and I believe still in terms of duration) and I heard almost nothing about it in the enthusiast community. I figured I must be dealing with one monotonous, overly-long mine ride for it to warrant so little talk, either in praise or condemnation of the ride. I expected given my tastes that I would respond more favorably than average and note that it was an underrated, fun gem, but surely it lacked the aggressiveness or narrative sequence that other greater rides had. But in the month or two leading up to my visit I began to hear more and more whispers I couldn’t block out that maybe there was a bit more to the Ultimate than I had originally figured. Could it be that this ride I was already eagerly anticipating just by virtue of not knowing the layout was in fact unknowingly destined to become one of my all-time favorites? Today was the day I would find out.

that maybe there was a bit more to the Ultimate than I had originally figured. Could it be that this ride I was already eagerly anticipating just by virtue of not knowing the layout was in fact unknowingly destined to become one of my all-time favorites? Today was the day I would find out.

To get to Lightwater Valley from my home base in York I needed to take a series of increasingly smaller busses, where I was eventually deposited at the mouth of a small drive in the middle of the green Yorkshire countryside with little resembling an amusement park save for the “Lightwater Valley Thataway” sign. Business didn’t appear to be particularly bustling yet but I expected given the pleasant weather I would not be alone for long. The biggest annoyance was the locker storage for my backpack;  £5 for a locker so small I was barely able to fit it in there, requiring that I carry my jacket around with me all day as well. Thankfully once that was all taken care of I found one of the most pleasant, green and homely amusement parks I had ever witnessed.

£5 for a locker so small I was barely able to fit it in there, requiring that I carry my jacket around with me all day as well. Thankfully once that was all taken care of I found one of the most pleasant, green and homely amusement parks I had ever witnessed.

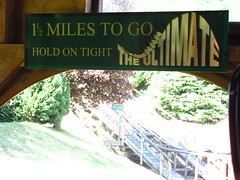

The walk to the Ultimate involves what seems to be at least a half mile of long, clear pathways set over grassy fields and through occasional thickets of trees with only the occasional amusement device or concession stand spoiling the stroll. Finally I spy the lift hill standing nobly behind the trees. The world’s longest roller coaster is fittingly housed inside the world’s longest station, all constructed in a manner that pleasingly says “in-house”. Same goes for the ride’s vehicles, an extraordinarily bulky design that seems like it might be terribly uncomfortable yet somehow the opposite is the case. There’s enough room for riders with a wider girth, and more importantly the single lapbar restraint (no seatbelts) lowers to a fixed position above and away from your lap and gut. This is essential to the ride’s success as a tight-fitting restraint would easily magnify every bump and jolt to cause bruising on contact, and given that our trackwork for this ride was partly engineered by the good folks at British Rail, this might be a very real concern. I’m warned I’ll have to wait an extra cycle for the front row. I assure them that I have waited long enough for this moment that I can hold out for another seven minutes.

design that seems like it might be terribly uncomfortable yet somehow the opposite is the case. There’s enough room for riders with a wider girth, and more importantly the single lapbar restraint (no seatbelts) lowers to a fixed position above and away from your lap and gut. This is essential to the ride’s success as a tight-fitting restraint would easily magnify every bump and jolt to cause bruising on contact, and given that our trackwork for this ride was partly engineered by the good folks at British Rail, this might be a very real concern. I’m warned I’ll have to wait an extra cycle for the front row. I assure them that I have waited long enough for this moment that I can hold out for another seven minutes.

“1½ miles to go…”___________________

Like the Beast, the Ultimate strategically remains hidden from view until the moment I crest the lift hill, the teasing of future possibilities maintained until the last moment… and even then it’s rarely a glimpse beyond the immediate next section of the layout. My lead car hangs over the triangular first drop for what seems like at least a third the vertical distance while I wait for the rest of the 10-car train to catch up. Finally we get enough weigh to pull the back half of the train the rest of the way off the lift and I begin freefalling down the perfectly straight ramp. I always enjoy first drops that lack a consistent curvature despite the necessary absence of any negative G-force because there’s a clearer sense of acceleration downhill and the jolt into the pullout acting as a better payoff signaling that the journey has officially commenced. Once I do hit that pullout the rest of the layout will follow the contours of the land (some of it artificial) never leaving more than a few feet from terra firma, an extremely effective tactic to increase the sensation of speed and moving rapidly through space, plus it tends to better keep secrets hidden.

The first secret is that the Ultimate actually has some pretty good airtime, made all the better by the roomy seats. Pushed up and over a low, circular airtime curve over a small man-made hillside, this is repeated twice more over smaller variants with a slight left curve thrown in. So far so fun, and all the more so for the quirky engineering. The track flattens out and I cruise along next to a cow pasture before skirting between a shaded thicket of brush. There’s no clear narrative motive to the layout yet, we all seem to be flowing with the natural environments on a roller coaster constructed as much by man as by nature. In fact I’m noticing that it seems with such a long train we seem to be having a difficult time maintaining its speed after what doesn’t seem to have been a very long distance so far, and we don’t seem to be traveling uphill but I could be wrong about that.

a very long distance so far, and we don’t seem to be traveling uphill but I could be wrong about that.

That’s no difficulty for the Ultimate though. When the going gets tough, the tough gets weird. The next thing I realize the Ultimate is throwing a series of seven, two foot tall bunny hops at me, apparently because no one had any better ideas for what to put between here and the second lift hill. I likely would have reached the same solution if I were building a roller coaster in my backyard back when I was twelve. If one is expecting any violent airtime they won’t find it as we’ve already just about run out of steam that making it over hills this small proves to be a challenge, but the quizzical look on my face as we lurch back and forth, over and over again, summarizes the WTF nature of the experience perfectly and is a suitably offbeat closing thought for the Ultimate’s first act.

over and over again, summarizes the WTF nature of the experience perfectly and is a suitably offbeat closing thought for the Ultimate’s first act.

With a second slow chain lift that doesn’t even have an immediate drop-off on the other side like the first one, there’s plenty of time to think about where I’ve been and where I’m headed. A couple things up for analysis: the first half was quite fun but very arbitrary, starting as a real coaster and then ending as a parody of itself. I’m also a bit concerned that the inability to maintain speed may bode bad things for the return run, since the layout forms something of a large rectangle and the first side we’ve completed includes both lift hills sandwiching the track, while the return run we’re facing is all gravity-driven track all the way back to the station. Will we have enough momentum to get home? Empirical evidence suggests it does, but if the lift hills are the same height and we barely completed the first half, how? I think the profile of the hills may have something to do with it. Since the train is so long you wouldn’t calculate the distance of freefall from peak to trough on the track, but rather from the peak to trough of the train’s center of gravity. Since the first lift had a very sharp drop-off at the top the center of gravity was probably some 15 feet below the top of the track; the same is true of calculating the ‘bottom’ of the drop. Since the second hill has a long flat section at the top the train’s center of gravity would be equal to the maximum track height, so there could potentially be a very significant difference in the falling distance that contributes to speed despite the identical length.

Will we have enough momentum to get home? Empirical evidence suggests it does, but if the lift hills are the same height and we barely completed the first half, how? I think the profile of the hills may have something to do with it. Since the train is so long you wouldn’t calculate the distance of freefall from peak to trough on the track, but rather from the peak to trough of the train’s center of gravity. Since the first lift had a very sharp drop-off at the top the center of gravity was probably some 15 feet below the top of the track; the same is true of calculating the ‘bottom’ of the drop. Since the second hill has a long flat section at the top the train’s center of gravity would be equal to the maximum track height, so there could potentially be a very significant difference in the falling distance that contributes to speed despite the identical length.

This theory seems at least semi-plausible (and honestly I’m a bit impressed the designers thought to take this into consideration when so much else about the ride seems woefully makeshift) and a test in the front seat seems to confirm this hypothesis when we’re much quicker to start gaining speed off the second drop than the first. Down I go, into a valley clearing through a gap in the trees…

And then…

I’m never one for conspiracy theories although I do suspect it probable that large-scale, carefully orchestrated conspiracies have been planned at various points in history ; obviously it’s only the bad conspiracies we hear of. Based on the relative quiet surrounding the Ultimate in the enthusiast community I figured the whole ride would, ultimately, be rather tame. Enthusiasts do not generally stay silent about rides that are on the extreme; regardless of whether it’s Intimidator 305 or Goudurix, rides that exert significant physical force on one’s body always accumulate some online notoriety. Maybe just in my attempts to shield myself from any spoilers about the Ultimate I somehow missed what everyone was already saying, but to suddenly be confronted with what is – unquestionably! – the most insanely intense, white knuckle, balls-to-the-wall section of roller coaster track I have ever experienced in all of my travels… and having not expected it, that can only mean a conspiracy is afoot to keep quiet the truth about the Ultimate to the rest of the world.

; obviously it’s only the bad conspiracies we hear of. Based on the relative quiet surrounding the Ultimate in the enthusiast community I figured the whole ride would, ultimately, be rather tame. Enthusiasts do not generally stay silent about rides that are on the extreme; regardless of whether it’s Intimidator 305 or Goudurix, rides that exert significant physical force on one’s body always accumulate some online notoriety. Maybe just in my attempts to shield myself from any spoilers about the Ultimate I somehow missed what everyone was already saying, but to suddenly be confronted with what is – unquestionably! – the most insanely intense, white knuckle, balls-to-the-wall section of roller coaster track I have ever experienced in all of my travels… and having not expected it, that can only mean a conspiracy is afoot to keep quiet the truth about the Ultimate to the rest of the world.

Basically the ride sweeps back and forth across a valley several times following inclined s-curves. Going about 60 MPH along track better designed for 35. And it was designed by people that not only had never ridden a coaster themselves, had never actually seen a roller coaster before figuring out how to build their own. The result is something that, several months later, I am still at a loss of words to describe, unsure how something so wrong could also be so right. The roomy vehicles must have been the difference between pleasure and pain, and I doubt many people recognize a difference in the case of the Ultimate. I’ve been beginning to think there is no fundamental difference between the two, one’s nerves don’t come with normative values, they either register sensation or they don’t, and it’s up to our cultural conditioning to interpret the patterns and decide whether to like it or not. It’s like walking barefoot on the sidewalk during the middle of July and the asphalt is so hot it starts to feel cold. That’s the sort of extreme we’re dealing with on the Ultimate, and those that can’t deal with it don’t deserve to call them self a coaster enthusiast. Live for once, experience something real. This is why we got into the hobby in the first place, isn’t it?

sensation or they don’t, and it’s up to our cultural conditioning to interpret the patterns and decide whether to like it or not. It’s like walking barefoot on the sidewalk during the middle of July and the asphalt is so hot it starts to feel cold. That’s the sort of extreme we’re dealing with on the Ultimate, and those that can’t deal with it don’t deserve to call them self a coaster enthusiast. Live for once, experience something real. This is why we got into the hobby in the first place, isn’t it?

Finishing with this sequence (watch out for the deer grazing nearby!) the train tips out of the valley at the top of one of the switchbacks and follows a long, straight stretch of track. Now that the Ultimate has quit the playful games of the first half and bared its true fangs at us, this moment of tranquility has an alarming quality to it, aware that the rate of speed we’re blazing through the trees has the very real potential to turn evil at any second. You can let it play mind games with you and become psychologically anxious, or you can simply accept the fact that, yes, more evil is around the corner, in the form of a small bunny hill with a sharp, unbanked curve hidden on the other side. The hole in the sole of my shoes was not getting smaller as I tried desperately to maintain posture against these assaults. The ride shows signs of slowing down but I’m not in the clear yet; a figure-eight with the lower track buried in a tunnel closes out the ride. This isn’t the colossal maelstrom of a grand finale like on other rides, just a new and original flavor of avant-oddity to let linger before parting ways.

has an alarming quality to it, aware that the rate of speed we’re blazing through the trees has the very real potential to turn evil at any second. You can let it play mind games with you and become psychologically anxious, or you can simply accept the fact that, yes, more evil is around the corner, in the form of a small bunny hill with a sharp, unbanked curve hidden on the other side. The hole in the sole of my shoes was not getting smaller as I tried desperately to maintain posture against these assaults. The ride shows signs of slowing down but I’m not in the clear yet; a figure-eight with the lower track buried in a tunnel closes out the ride. This isn’t the colossal maelstrom of a grand finale like on other rides, just a new and original flavor of avant-oddity to let linger before parting ways.

And what a sad moment that is with the realization that our time is finally at an end, over seven minutes after it began. There’s an epic quality to this ride that is sorely lacking from the vast majority of roller coaster experiences (and I use “epic” more formally than the kids today do). I not only left the ordinary world behind, I had been away for so long I began to forget it ever existed at all. Part of the reason I consider coasters to have potential to become their own unique artform is because, like other artforms, it is beyond the capacity of language to fully describe their experiential perception. That’s the realm of pure aesthetics, and it is always more true in the case of bone-rattling rides like the Ultimate where one is nearly incapable of thinking in any language while on board except for a string of instinctual profanities. It’s a new way of realizing one’s being-in-the-world, and after seven minutes inhabiting the aesthetic language of the Ultimate it’s disheartening to remember that the rules of ordinary social living must once again apply when it’s finally finished. That has become such a rare joy to feel oneself in the presence of something so radically original and great that the glowing sensation had to be cherished for as long as it would last.

while on board except for a string of instinctual profanities. It’s a new way of realizing one’s being-in-the-world, and after seven minutes inhabiting the aesthetic language of the Ultimate it’s disheartening to remember that the rules of ordinary social living must once again apply when it’s finally finished. That has become such a rare joy to feel oneself in the presence of something so radically original and great that the glowing sensation had to be cherished for as long as it would last.

There’s a long, gentle bend that leads us back to the station that’s visible from the park’s midways. “Why does everyone look like they’ve seen a ghost, surely this ride isn’t that wild,” I imagine spectators musing before finding out for themselves. In place of a brake run we get a small lift hill to aid the train back into the station. By this point I am absolutely blown away. New favorite European thrill ride for sure, the only question I had left was whether it would crack my top three favorite steel or not. To determine that I went back to my wooden coaster rankings to see how it held up to that similarly oriented ride that I once declared the Greatest Roller Coaster Ever Built: The Beast.

On a superficial level and indeed on many deeper levels the Beast and the Ultimate are very similar rides. Aside from being the world’s longest roller coasters with two lift hills spanning a wooded terrain setting, both have the grandeur and “escape to another world” quality that few others have. Plus (and this is probably the most important attribute for anyone that likes reckoning themselves as a non-conformist), they are both extremely singular experiences that fall outside categorization of any other established critical paradigm; to genuinely appreciate either the Beast or the Ultimate requires a willingness to strip oneself of all prior knowledge of what is ‘good’ or ‘bad’ about roller coasters.

On a superficial level and indeed on many deeper levels the Beast and the Ultimate are very similar rides. Aside from being the world’s longest roller coasters with two lift hills spanning a wooded terrain setting, both have the grandeur and “escape to another world” quality that few others have. Plus (and this is probably the most important attribute for anyone that likes reckoning themselves as a non-conformist), they are both extremely singular experiences that fall outside categorization of any other established critical paradigm; to genuinely appreciate either the Beast or the Ultimate requires a willingness to strip oneself of all prior knowledge of what is ‘good’ or ‘bad’ about roller coasters.

That’s where the comparisons end, and I will conclude by stating that not only do the Ultimate and the Beast have many differences, they inhabit polar opposite ends of a philosophical spectrum that makes one barely resemble the other. The Beast is an ultra-disciplined exercise in minimalism where every moment is so rationally dependant on the other that the concept of a ‘moment’ starts to lose its meaning. This minimalistic orientation results in the accumulation of a powerful psychological anxiety… which I should note (there was some confusion in my original review of that ride) is very different from psychological fear, not where it grabs you and makes you think “woah, another straight ramp, shit’s getting real!” This is similar to what an existentialist would describe as the anxiety towards death versus a fear of death (if in fact there is any difference between that and the Beast

and I will conclude by stating that not only do the Ultimate and the Beast have many differences, they inhabit polar opposite ends of a philosophical spectrum that makes one barely resemble the other. The Beast is an ultra-disciplined exercise in minimalism where every moment is so rationally dependant on the other that the concept of a ‘moment’ starts to lose its meaning. This minimalistic orientation results in the accumulation of a powerful psychological anxiety… which I should note (there was some confusion in my original review of that ride) is very different from psychological fear, not where it grabs you and makes you think “woah, another straight ramp, shit’s getting real!” This is similar to what an existentialist would describe as the anxiety towards death versus a fear of death (if in fact there is any difference between that and the Beast at all; it may easily be part of the same solid black painting).

at all; it may easily be part of the same solid black painting).

The Ultimate, on the other hand, is anything but. Each moment occurs independently of the other, and the narrative does not progress ‘towards’ anything at any moment. Instead you simply exist in one of three static states: happy Dadaism, evil Dadaism, and waiting for one of the previous two. Although there is a general dramatic structure to this sequence, the Ultimate otherwise is a ride of pure chance, an experience crafted more by the natural world once the humans that built it lost control over what sort of physical sensations would be resultant and were just blindly constructing whatever looked right from the ground. One could almost call it a nihilistic roller coaster if only it weren’t clear that no human had a conscious, deliberate part in the chaos that ensues (I guess that depends on if you define ‘nihilism’ within the context of human intentions or not). The Ultimate is the Jackson Pollock to the Beast’s Piet Mondrian, an aleatoric John Cage performance to a minimalist Philip Glass composition;

Although there is a general dramatic structure to this sequence, the Ultimate otherwise is a ride of pure chance, an experience crafted more by the natural world once the humans that built it lost control over what sort of physical sensations would be resultant and were just blindly constructing whatever looked right from the ground. One could almost call it a nihilistic roller coaster if only it weren’t clear that no human had a conscious, deliberate part in the chaos that ensues (I guess that depends on if you define ‘nihilism’ within the context of human intentions or not). The Ultimate is the Jackson Pollock to the Beast’s Piet Mondrian, an aleatoric John Cage performance to a minimalist Philip Glass composition; for the indiscriminate philistine they are both indistinguishably obtuse, but for the savvy connoisseur the difference is as great as night and day.

for the indiscriminate philistine they are both indistinguishably obtuse, but for the savvy connoisseur the difference is as great as night and day.

This is starting to get a bit obscure so I’ll summarize. I personally still find the Beast accomplishes far more by the end of its circuit even though on the surface the Ultimate seems to ‘do’ more. I’m missing the same simple poetry from the Ultimate… as well as the ability to ride after dark. A lot of the distinction may come down to my own personal preference for strong narratives. However, the Ultimate remains one of the best rides I’ve found on the planet. Few other layouts manage to cover as much ground (physically and across the emotional spectrum) whilst standing completely outside any traditional roller coaster milieu. When one rides the Ultimate for the first time they are assured they will have an individually authentic reaction when they return to the station; be it positive or negative, it is a non-relational experience that cannot be substituted by prior events or testimonies. Plus, for me, being able to ride it ‘blind’ for the first time makes it all the better.

Actually I lied; I didn’t ride the Ultimate completely blind the first time. I originally became familiar with the layout over a decade ago when it was known as the Storm at Katie’s World (aka Katie’s Dreamland) in the original RollerCoaster Tycoon. The first time I saw it I remember commenting that it seemed like a ride a little kid would make; after the first lift a singular hill following the isometric terrain before another lift, the empty hole of unsold land in the middle, the long elevated straightway against the far edge of the game grid. Despite being my first time to Lightwater Valley, it was a bit of a nostalgic trip back in time having grown up on RollerCoaster Tycoon and seeing the parkscapes that gave inspiration to that game’s unique appearance that is still without peer in this day of 3D rendered graphics.

like a ride a little kid would make; after the first lift a singular hill following the isometric terrain before another lift, the empty hole of unsold land in the middle, the long elevated straightway against the far edge of the game grid. Despite being my first time to Lightwater Valley, it was a bit of a nostalgic trip back in time having grown up on RollerCoaster Tycoon and seeing the parkscapes that gave inspiration to that game’s unique appearance that is still without peer in this day of 3D rendered graphics.

“Look, there’s Richard’s Wreckers, with the little inlet pathway with benches! And there’s Al’s Galleon behind the trees! Is that the lone black swan on Catherine’s Cruisers I spy through the trees? And whatever happened to the Forest Flyer? I loved that ride.”

Nearby the Ultimate is the Runaway Plumber. (Oops, I mean the former Rat Ride, given a retheme in 2010 and now known as the Raptor Attack; I think plumbers on the lam would make a better theme, don’t you agree?) The ride is a simple Schwarzkopf Wildcat layout housed indoors, but with a most brilliant of setups prior to the ride in the form of a lengthy walk through what seems to be an authentic sewage line, complete with running, dripping water everywhere. Given that you enter the tunnel at ground level and then descend a good fifty-foot staircase I would have literally been convinced that the entire ride takes place in a subterranean bunker left over from the Cold War had it not been for some leaked light on the far wall of the main ride chamber giving it away as built on a hillside. Thankfully I didn’t discover

Nearby the Ultimate is the Runaway Plumber. (Oops, I mean the former Rat Ride, given a retheme in 2010 and now known as the Raptor Attack; I think plumbers on the lam would make a better theme, don’t you agree?) The ride is a simple Schwarzkopf Wildcat layout housed indoors, but with a most brilliant of setups prior to the ride in the form of a lengthy walk through what seems to be an authentic sewage line, complete with running, dripping water everywhere. Given that you enter the tunnel at ground level and then descend a good fifty-foot staircase I would have literally been convinced that the entire ride takes place in a subterranean bunker left over from the Cold War had it not been for some leaked light on the far wall of the main ride chamber giving it away as built on a hillside. Thankfully I didn’t discover that until after the ride was halfway complete so the illusion had not yet been spoiled when I first pulled down my lapbar and wondered what awaited me within.

that until after the ride was halfway complete so the illusion had not yet been spoiled when I first pulled down my lapbar and wondered what awaited me within.

Comfortable, non-restrictive seating, a long, dark anticipation around slow turns and lifts before the big drop finally hits, and then a smooth, fun ride with a few small pops of airtime and a decently long ride time that’s neither over too soon nor overstays its welcome… it all makes me momentarily suspect that if our egos weren’t all so big we’d be seeing these sorts of attractions on more top ten lists, yet fifteen minutes later I somehow start to forget how much fun it really was. Fantastic ride, plus it decentralizes what would have been a monopoly of attention on the Ultimate.

About the Jurassic Park retheme, I’m not sure what the ride was like before but I got the sense it wasn’t wholly necessary, yet it was done well enough that I didn’t think it was an unwelcome addition either. The setting of the attraction is amazing enough as it is, I was worried that trying to give it a serious but patently artificial theme would cheapen the authenticity of the whole underground experience that hadn’t previously been threatened by the kitschy Rat Ride theme. That might all be true, but it’s all integrated well enough that you don’t see the cracks of where the concrete fossils were added, and the velociraptors along the main ride still add to the experience by adding a few jarring gotcha moments to places where the natural ride pacing might have needed a pick-me-up. It’s dark enough in there you can’t see them coming until the moment you pass by, and then it’s all strobes, lunging animatronics mere feet away, and sudden, primordial screams before suddenly plunging into darkness again.

a pick-me-up. It’s dark enough in there you can’t see them coming until the moment you pass by, and then it’s all strobes, lunging animatronics mere feet away, and sudden, primordial screams before suddenly plunging into darkness again.

With the two starring attractions crossed off my list, I was granted time to explore the rest of the park and its more humble pleasures. The first ride was humble enough, the Tivoli Ladybird roller coaster. Literally, I laughed at the quaintness of the small, compact layout with tiny vehicles that shifting my weight would nearly have an impact on the ride’s dynamics by the thought of comparing it to the extravagant excess of the Ultimate right down the pathway. The RollerCoaster Tycoon ride vehicles were an extra plus.

More substantial was the Twister, a Reverchon spinning coaster. Another fine example of a well-conceived production model that provided a tremendous amount of spin in my case, I nevertheless found time for only the one ride during my day as it seemed a bit redundant with the superior Raptor Attack already nearby.

Deeper exploration was needed to add the final roller coaster to my count, which I nearly would have given up as having been quietly removed in the offseason had I not briefly glimpsed it through the trees on my walk into the park. Eventually I did stumble across the Caterpillar, where I learned that I was not the only one that had trouble locating it amid the foliage, as the lonely operator on duty informed me that despite it already being a few hours after park opening, I was the first person to take a ride that day. As for what everyone was missing out on… well, it was no Ultimate.

it through the trees on my walk into the park. Eventually I did stumble across the Caterpillar, where I learned that I was not the only one that had trouble locating it amid the foliage, as the lonely operator on duty informed me that despite it already being a few hours after park opening, I was the first person to take a ride that day. As for what everyone was missing out on… well, it was no Ultimate.

That entire corner of the park was very densely forested, very natural and rustic, similar in tone to Knoebels except with far more breathing room between rides. Despite being tight on time I was sure to not rush through these pathways. The Lightwater Wheel was required to get a sense of the layout from above the trees, and even then as the pictures below are testament to, you can’t see very much (not helped by the Plexiglas reflections).

Although assorted other flat rides were scattered throughout the premises, I neglected to ride any more apart from the aggressively named Falls of Terror, a dinghy boat water slide with a few rather sharp looking drops. The ride was a successfully fun one, although I was left stranded at the top for a good ten minutes as I waited for another single rider to happen along, as they have an odd policy requiring two people per raft. Thankfully some lovely views on a clear blue June day were afforded from the top.

Lightwater Valley is an exceedingly charming park, perhaps the most pleasurable in the UK to simply stroll the premises. That claim is made with some hesitation, respecting the more beautiful (but always crowded and sometimes too self-serious) Alton Towers or the more eclectic (but run under management that seems to not realize their competitive advantage) Blackpool Pleasure Beach, but regardless when I think of which park I’d most want to return to in the UK, it would probably have to be Lightwater Valley. A plethora of grassy fields and a dearth of fencing and midway ornamentation make for a pleasing aesthetic cocktail, and a few trails hidden deep in the trees make for good variation as well. I might propose however that they dispense with some of the colorful, temporary carnival rides, as these tend to clash with the natural beauty of the area which is better served by the permanent stone, brick and wooden structures. I wouldn’t mind the Twister and a few other flats go the wayside in favor

the more beautiful (but always crowded and sometimes too self-serious) Alton Towers or the more eclectic (but run under management that seems to not realize their competitive advantage) Blackpool Pleasure Beach, but regardless when I think of which park I’d most want to return to in the UK, it would probably have to be Lightwater Valley. A plethora of grassy fields and a dearth of fencing and midway ornamentation make for a pleasing aesthetic cocktail, and a few trails hidden deep in the trees make for good variation as well. I might propose however that they dispense with some of the colorful, temporary carnival rides, as these tend to clash with the natural beauty of the area which is better served by the permanent stone, brick and wooden structures. I wouldn’t mind the Twister and a few other flats go the wayside in favor of a medium sized wooden coaster.

of a medium sized wooden coaster.

The majority of my day was spent on the Ultimate, which actually became the one souring impression the park left with me. I loved the ride all too much, as I was willing to put up with a nearly 45 minute queue by the end of the day despite everywhere else being close to deserted. It wasn’t that the Ultimate was that particularly popular (although it was unquestionably the most popular attraction), just that the throughput was significantly reduced. A single train operating on a ride that takes over seven minutes to complete a circuit would be bad enough but perhaps necessary given that this ride surely beats itself up a fair amount, but having that train operate with the back four cars filled with water dummies made it all the more frustrating to watch unused seats go out while I remained stuck on the platform aware that once 3:00pm rolled around I would have to depart with my final ride from the park possibly forever. Of course I was made late anyway and I had to run back to the roadside to prevent from missing my bus, as my plans for the day had only just begun.

to watch unused seats go out while I remained stuck on the platform aware that once 3:00pm rolled around I would have to depart with my final ride from the park possibly forever. Of course I was made late anyway and I had to run back to the roadside to prevent from missing my bus, as my plans for the day had only just begun.

Next: Edinburgh

Previous: Flamingo Land

(Credit for all backstage photos of the Ultimate to Nathan Lawson and Valley Mania. Used with permission.)

Comments